Sudan, an ignored tragedy

Although the almost permanent news blackout on what was happening there has prevented the reality of the situation from becoming known, it has only deteriorated and laid the groundwork for what is happening now.

Once again, geographical remoteness may lead us to think that what happens there will not affect us. And nothing could be further from the truth. The situation in Sudan must be framed within the context of what is happening on the African continent, and more specifically in the Sahel. In this remote area of East Africa we already have a failed state for decades that has served as a breeding ground for jihadist terrorist groups and a haven for pirates that even forced the international community to organise a naval mission to deal with them. This fact alone should serve as an indicator for us to understand how our interests are also at stake there. If Sudan continues to drift into chaos and follows the same path as Somalia, the consequences could be unpredictable, especially given that it shares a border with Egypt and Chad, two countries that could easily catch the wave of instability and are already much closer to us.

Let us begin by focusing on the conflict and giving a brief summary of its origins. The conflict that led to the secession of South Sudan in 2011 took place during the mandate of former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. He was also responsible for the state-sponsored spiral of violence in the Darfur region, which led to charges of war crimes and genocide.

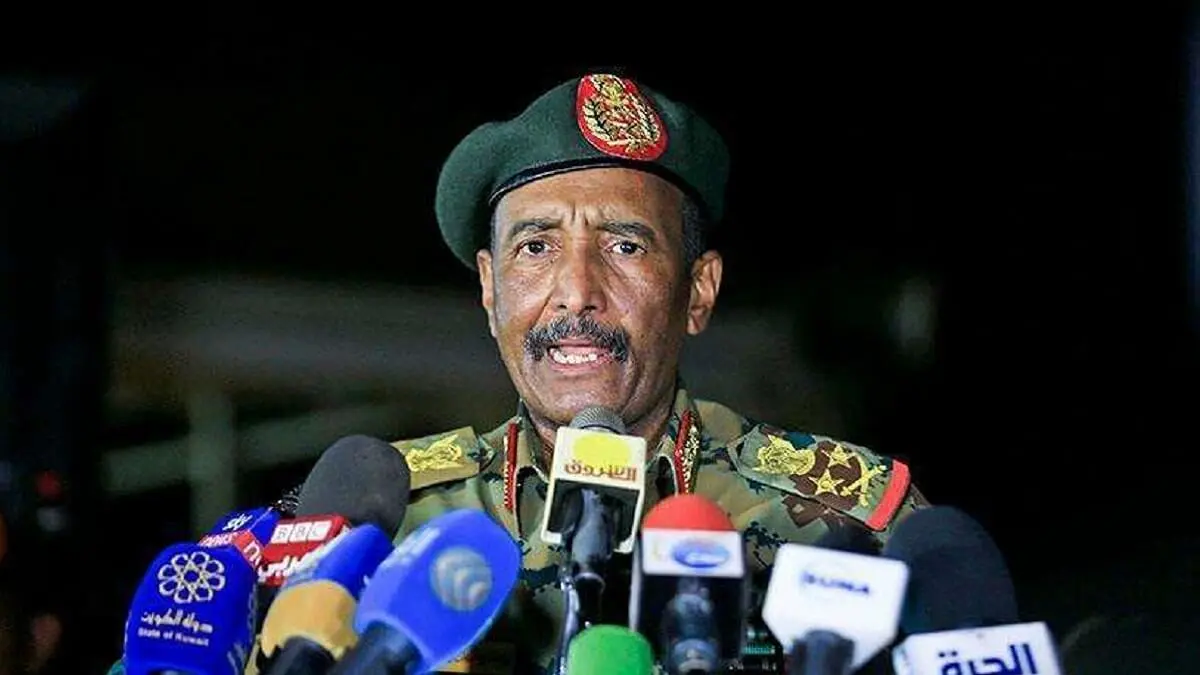

In 2019 he was ousted, tried and convicted of corruption and other crimes. However, the armed forces regained strength in 2021 following a coup that brought to power an interim unity government led by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. This government committed to a handover to a civilian-led government in April 2023. Following the pattern we have seen in other countries in the region, the agreement was delayed for unclear reasons, increasing tensions between rival military leaders such as General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, both of whom serve as President and Vice-President of the Sovereign Council of Sudan, respectively.

FAR is a paramilitary organisation that inherited from the Janjaweed militia. In 2019, they took part in the crackdown on demonstrators protesting against the Al-Bashir government in Khartoum. After the fall of Al-Bashir, attempts were made to agree on a period of integration of the FAR into the structure of the Armed Forces, but there was no agreement on the terms and timeframe.

In an atmosphere of growing tension, exacerbated by the galloping economic crisis, on 11 April, FAR elements were deployed near the town of Merowe as well as in Khartoum. Government forces tried to force their withdrawal but refused. The fighting began when FAR took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum.

Thus, we can place the beginning on 15 April 2023, as a result of clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the Rapid Support Forces led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo throughout the country. On that day, fighting even reached the presidential palace, the headquarters of the SAF and the Khartoum and Merowe airports. Clashes quickly became widespread, with reports of gunfire and clashes in Khartoum and El Obeid in North Kordofan.

The various insurgent groups already operating in the country, especially in the hard-hit Darfur region, were taking sides and joining one side or the other. Thus, in June, the SPLM-N (Al-Hilu) confronted the army by positioning itself alongside the FAR, and in July, a faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement led by Mustafa Tambour (SLM-T) officially joined the war in support of the Sudanese Armed Forces, while in August, the Darfur and Kordofan-based Tamazuj rebel movement joined forces with the FAR. All of this made it clear that we were facing a civil war that had been simmering for years and could develop into a new failed state.

From October 2023, government forces began to lose steam and the balance of power shifted in favour of the FAR. This was evident in the defeat of the SAF in Darfur, where the FAR managed to take over the city of El Fasher, which is also home to a major airport, and also made gains in Khartoum State and Kordofan. Subsequent negotiations between the warring parties have so far failed to produce significant results, while many countries have provided military or political support to Al-Burhan or Dagalo.

In November, the SAF recaptured four of Darfur's five states, sparking fears of an imminent SAF assault on Al-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, prompting Darfur's rebel factions and ethnic militias to unite in defence of the city. Clashes began in mid-December, again resulting in heavy civilian casualties and further displacement.

Since the beginning of the conflict, there have been several initiatives for peace talks, most notably the Jeddah Treaty. However, they have all failed one after the other.

After a year of fighting between the army and the Rapid Support Forces, violence has only escalated, especially in Darfur. Some milestones, such as the killing of more than 800 ethnic Masalits by the FAR, momentarily attracted international attention, but that attention has been short-lived. The killing in mid-November of some 800 people, mostly from an ethnic minority - the Masalit ethnic group - by the Rapid Reaction Forces set off alarm bells in the international community.

The violence has spread beyond Darfur and now reaches every corner of the country, and there is every indication that the prolongation of the fighting will plunge Sudan into a state of chaos that will provoke a humanitarian crisis even greater than the one already being experienced.

By way of fact, since the outbreak of the conflict, more than 13,000 Sudanese have died as a result of the conflict, although the actual figure may be significantly higher. Between 1 December 2023 and 26 January 2024, 1,300 people were killed, most of them concentrated in Khartoum and Aj Jazirah, following the capture of Wad Madini The conflict appears to be intensifying and spreading eastwards into the heavily contested east, posing an increased risk of atrocities and mass displacement. Both the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Action Forces are receiving support and resources from third parties to enable them to continue fighting. The UAE is arming the FAR, Egypt, and possibly Iran, among others, are providing support to the SAF. Formal discussions between the parties to the conflict have been limited to technical and low-level issues, without addressing the broader issues that fuel the conflict.

The cross-border dynamics and communal ties of the tribes and ethnic groups involved in the Sudanese conflict could affect the stability and security of neighbouring countries such as Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR). These countries are already receiving refugees and returnees, requiring measures to contain potential spillover effects from tensions over both ethnic rivalries and lack of resources. Chad, CAR and Sudan have in common communities involved in one way or another in the conflict and whose movement has so far not been stopped by administrative borders, such as the Rounga, Zaghawa, Massalit and various Arab tribes.

In addition to the death toll, the reality of this conflict is that it has caused the internal displacement of 5.3 million people and driven 1.3 million out of Sudan. All this in a country where more than 50% of the population is unemployed and where basic infrastructure, already scarce, is being systematically destroyed by both sides.

If we take all this data coldly and seriously, we realise the magnitude of the tragedy and the enormous problem that is brewing in East Africa. If what is happening is not stopped and Sudan ends up drifting like Somalia, we can safely say that sooner rather than later Chad or the Central African Republic will be dragged into the same abyss, and that is something we cannot afford. As we noted last week, the greatest threat to Europe comes from the African continent, and life as we know it is inexorably dependent on stability in those lands. The ostrich technique has never worked and, if Europe does not get its head out of the ground soon, by the time it does, it will be too late.