The Houthi militia, an unusual prominence

Some believe that Hamas has at least partially achieved its objectives. However, nothing could be further from the truth.

So far, it has only succeeded in getting Israel to raze the Gaza Strip (with sometimes highly reprehensible methods and consequences) and eliminate Hamas's operational capacity (and all without the international reaction of condemnation they hoped to provoke), that the operation continues on the same terms, but against Hezbollah, and again without the timid or limited protests affecting Tel Aviv in the least, and that Iran's involvement has been as limited as Israel's response to the attacks received.

In other words, the terrorist group's ‘win-win’ theory, that if they overpowered Israel they would win, and if Israel reacted, there would be an earthquake of protest in the Muslim world that would probably lead to a regional conflict in which they would regain lost support, which would also be a victory, has collapsed irrefutably.

It might even be inferred that Iran has left its proxies, if not alone, then quite helpless. Perhaps the risk of unwanted escalation is too great. Or perhaps its pawns decided to act on their own or without sharing the true magnitude of what they were planning, and that put Tehran in a very complicated position.

Hamas's action and Israel's subsequent reaction spurred the other Iranian militias to react in support of their allies - in fact, it was the only real and effective support that was forthcoming. The main ones were Hezbollah and the Houthi militias. The former have followed the same path as Hamas, something we had already noted would happen almost as early as 7 October. However, the Yemeni militia has demonstrated capabilities and determination that deserve a closer look, as they are great unknowns who, as we have seen, can put part of the world economy in check with their actions in the Gulf of Aden.

And this does not seem far-fetched when we see an international coalition deploying dozens of warships to counter their attacks. Such a thing is not done if it is not considered vitally important.

The Red Sea, a key maritime link between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal, has for centuries been a hub of world trade. Its strategic location has made it an invaluable route for maritime traffic that has shaped the economic and political landscape, not only of the Middle East, but arguably of the entire world.

Historically, the Red Sea was a key part of the Spice Route, serving as a trade corridor for early civilisations, including the Egyptians, Phoenicians and Romans, transporting goods such as frankincense, myrrh and precious metals. Control of this waterway has long been disputed, and various empires have recognised its pivotal role in controlling trade and influence.

The Suez Canal, completed in 1869, revolutionised maritime trade by providing a direct route between Europe and Asia, avoiding the long and dangerous voyage around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa.

The construction of the canal was a testament to human ingenuity and ambition, and forever altered the pattern of world trade and navigation. Today, approximately 12% of world trade passes through the Suez Canal, underlining its position as one of the busiest maritime trade routes in the world. To get some idea of the impact of a blockage of this sea route, we need only go back a little more than a couple of years ago, when a container ship of the Evergreen company blocked the canal for a few weeks. The consequences then continued to be felt more than a year later.

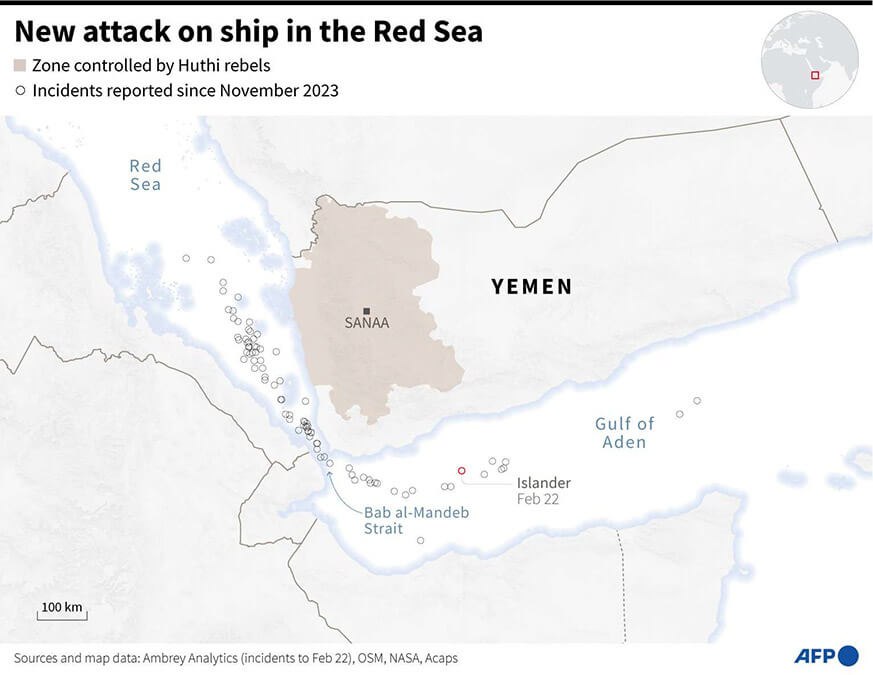

The stability of the Red Sea region is crucial to maintain the uninterrupted flow of trade from the Bab el Mandeb to Suez. In this scenario, the emergence of the Houthi insurgency in Yemen raises a multitude of security concerns, as, in the current context, the insurgent group targets ships using this sea route, threatening one of the world's major maritime choke points, the Bab el Mandeb Strait. The implications of these disruptions are far-reaching, affecting not only regional but also global trade dynamics.

The Yemeni Shia militia, supported by Iran through the Quds force, has been used by Tehran to try to undermine the stability of its main enemy and competitor in the region, Saudi Arabia, and through this support they have acquired an increasingly sophisticated arsenal, posing a greater threat to commercial shipping.

Not surprisingly, the group has claimed responsibility for a growing number of high-profile incidents. These incidents have led to the deployment of an international naval coalition to secure passage through these waters, and even to the US using one of its most prized assets, B2 bombers, to attack pro-Iranian militia targets.

The conflict has immediately resulted in fluctuations in world oil prices, influenced insurance rates for shipping in the region, and prompted a reassessment of security strategies by shipping companies.

The tactics used by the Houthi rebels have evolved significantly and, although still underestimated by some, their ability to carry out targeted missile attacks and the strategic deployment of maritime drones and unmanned aerial vehicles poses a significant danger to commercial and military vessels. These actions have not only threatened the security of the Red Sea transit corridor, but have also had a ripple effect on international shipping and commercial practices.

Freedom of navigation is often at the epicentre of geopolitical confrontations with global repercussions.

These precedents highlight the critical role that unimpeded maritime passage plays in global trade and security. Analysis of past conflicts reveals a pattern in which threats to navigational rights not only adversely affect regional stability, but also have far-reaching implications for the global economy.

As an example, a little known fact. Between December 2023 and February 2024, maritime traffic of all types (containers, products of all kinds and crude oil), has suffered a decrease of between 48 and 72%. By contrast, the increase in the same traffic over the same period via the Cape of Good Hope route has increased by 64-73%. Needless to say.

A noticeable trend can be established in the frequency of attacks that seems to increase or be maintained at a steady rate over time. The incidents involve ships sailing under a variety of international flags, suggesting that these events are widespread and not limited to ships of a particular nation, which belies the claims that they only attack ships bound for Israel or whose companies have relations with the Hebrew country.

The timing of these attacks, while somewhat indiscriminate and taking advantage of windows of opportunity, may, at a given moment, reveal patterns or escalations in the conflict with Israel.

The fact that there are sometimes several simultaneous attacks on the same day suggests the possibility of coordinated actions, while the attacks that have been carried out using a sophisticated combination of missiles and unmanned aerial or naval vehicles point to a high level of strategic planning and capability on the part of the perpetrators, as well as the existence of intelligence support, and probably guidance, from Iran, and more specifically participation, targeting and guidance from a number of vessels deployed in the area.

These incidents, which we will not list here, highlight a significant level of maritime insecurity and the presence of complex threats to both commercial and military vessels.

The implications of this security landscape are far-reaching and have the potential to affect global trade, maritime law and international relations. And all this at the hands of a hitherto underestimated group that, against all odds, is becoming Tehran's most influential tool in the region. What happens in this corner of the world's most volatile region will have to be closely monitored.