Turkey at the crossroads

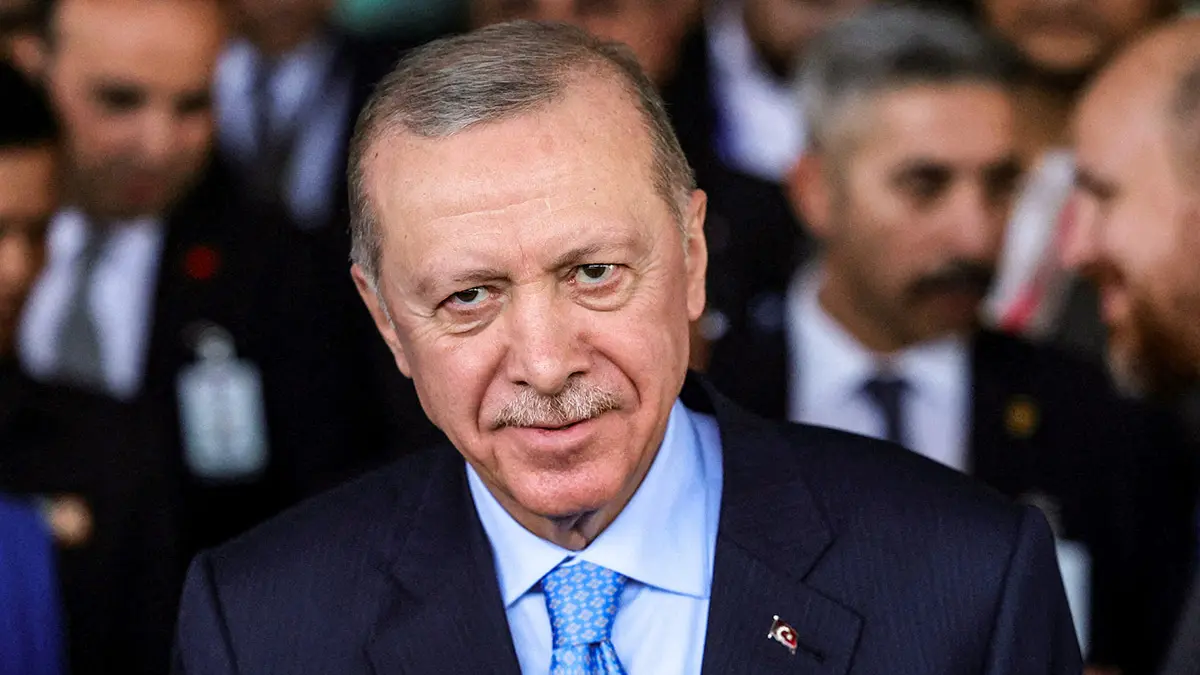

As if the conflict generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine were not enough, the first disturbing moves of the Trump administration (although it must be recognised that they should not have surprised anyone), the resumption of the war in Gaza, the Houthi attacks in the Strait of Bab el Mandeb, and the alarming news about the possible progress of the Iranian nuclear programme, Turkey, and more specifically President Erdogan, has taken another step on the road to authoritarianism, provoking major protests that place the country in an unstable and very dangerous position.

Turkey is a country that, despite its short history as a modern nation and its turbulent beginnings after the end of the First World War, has almost infinite potential and enormous geopolitical weight, largely marked by, as Tim Marshall would say, ‘The tyranny of geography’.

Not long ago I read the most brilliant summary I have seen on the origin of modern Turkey and I reproduce it here because it is very useful for understanding some elements of the current situation and its possible evolution: ‘In January 1919, the victorious countries of the Great War held a conference in Paris to set the conditions of peace with the defeated countries...’ ‘The San Remo conference, held in April 1920, continued the negotiations on the division of the remains of the Ottoman Empire, the terms of which were specified in the Treaty of Sevres, signed on 10 August of the same year...’ ‘...unhappy with the terms of the partition, Turkish nationalists, led by the most prestigious officer in the Ottoman Army, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, began the so-called Turkish War of Independence...’ ’...new borders were internationally recognised in June 1923, through the Treaty of Lausanne, and in October of that same year the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey was officially proclaimed. The leader who had promoted it, Mustafa Kemal, assumed the presidency and became Ataturk, father of the Turks...’ ‘... Ataturk set in motion the most ambitious political experiment in secular reform that an Islamic country would face throughout the 20th century...’ [i]

Many experts base the rapid development of a nation that is barely 100 years old and its prominence in scenarios where it is not usual to have Muslim countries on this secularisation. Even though religion is an important element of identity for Turkey and its people, unlike in most Muslim countries, it is not as present in political and economic life, etc.

However, since the arrival of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as prime minister in 2003, the country has taken a different course.

The former prime minister and current president of the Republic, a position he has held since 2014, has made no secret of his authoritarian character and his firm determination to accumulate more and more power and to remain at the head of the country at all costs. And one of the tools he has used has been to change course from what had been the great work of ‘Ataturk’, promoting a progressive Islamisation of the country.

When he came to power, Erdogan privatised large public groups such as Türk Telekom, the big gas and oil companies, ports and airports. He liberalised the labour market, reformed the banking and credit systems and fostered entrepreneurship. This policy significantly increased foreign investment and boosted growth in the early years, but at the same time a high level of corruption began to be perceived in which important families, including Erdogan's own family, benefited from these privatisations.

This drift, as well as the increasingly clear perception of Erdogan as an autocrat and the clear evidence of corruption and nepotism, were largely the cause of the coup d'état that took place in 2016 by a faction of the army with links to a former ally of Erdogan, Fetullah Gullen. The failure of this led to a purge at all levels of the state, with special emphasis on the armed forces, a situation that has continued over time and still endures.

In the 2020s, however, the Turkish economy went into free fall, reaching an annual inflation rate estimated at between 108% (according to the government) and 185% (according to independent estimates).

Despite the havoc wreaked by the COVID-19 pandemic, 2021 was marked by strong economic growth, with GDP expanding by approximately 11%. This rebound was largely due to the recovery of domestic and external demand following the restrictions of the pandemic. However, towards the end of the year, significant inflationary pressures began to emerge, driven by factors such as the depreciation of the Turkish lira and rising commodity prices. In 2022, the Turkish economy faced considerable challenges due to rising hyperinflation. In April, prices rose by 69.97% compared to the same month the previous year, seriously affecting the purchasing power of citizens and reducing domestic demand. This situation was exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and problems in global supply chains. But even despite these challenges, the economy managed to maintain positive growth, albeit at a slower pace than the previous year. Despite the poor international situation and facing all kinds of adversity such as the devastating earthquakes in the south-east of the country, the Turkish economy grew by 4.5% in 2023, slightly exceeding government forecasts, which was attributed to strong domestic demand that offset the negative effects of natural disasters. However, once again, inflation continued to be a significant problem, with rates fluctuating around 65% during the year.

Over the last two years, growth has been declining, and although monetary policies seem to have stabilised the situation somewhat, inflation continues at unbearable rates and the currency has not stopped devaluing. Volatility is the word that best defines the situation of the Turkish economy.

And it was precisely this factor, the economic one, that meant that the last elections were the first in almost twenty years in which the victory of the party in power was in doubt. The possibility of Erdogan's defeat had never been on the cards, and it is exactly that which has led the current president to take this dangerous step.

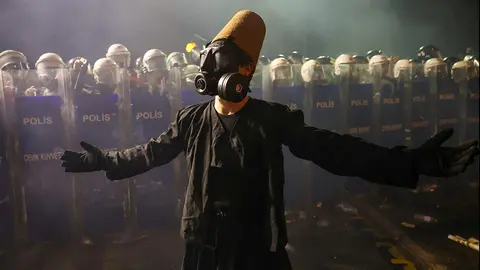

The arrest of the mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu, in the early hours of 19 March, a few days before his official nomination as presidential candidate by the main opposition party, the Republican People's Party (CHP), is nothing more than a new and alarming escalation in the continuous democratic regression of Turkey, which, however, should come as no surprise to anyone.

It is a calculated manoeuvre to eliminate one of the most popular opposition figures in the country and send a clear message to all those who dare to challenge the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

The timing of Imamoğlu's arrest has been carefully chosen. It is not the result of chance. Both national and international conditions are perfect for the AKP to have been able to act with minimal consequences.

Internationally, the return of US President Donald Trump has created a climate in which autocratic leaders feel emboldened or at least reassured. And given his past record, and his stated policy of not interfering in anything that does not directly affect the United States, it is to be expected that he has been counting on Washington not to challenge Turkey's actions.

On the other hand, recent events in Syria have increased Turkey's strategic importance. Following the collapse of the Assad regime and Iran's expulsion from key areas, Turkey has gained a lot of ground and the United States needs its cooperation to destabilise the region, especially to counter Iran's influence in the broader Middle Eastern security framework. The possibility of a conflict with Iran makes it highly unlikely that Washington will risk losing Ankara's support over the arrest of an opposition leader.

As far as Europe is concerned, the situation has also favoured Turkish action. The disengagement, at least in words, of the US from European security places Turkey - which has the second largest army in NATO - as an even more critical element in Europe's defence posture against Russia, although, and this is another possible consequence, the US has not withdrawn from the region. The USA's disengagement, at least in words, from European security places Turkey - which has NATO's second largest army - as an even more critical element in Europe's defence posture against Russia, although, and this is another possible consequence of the new geopolitical framework, it may lead Turkey to insist on its entry into the European Union as a consideration for its contribution to that defence against Russia. The EU governments, already struggling to reconfigure their security strategies in the wake of the war in Ukraine, do not seem to be in the best position to antagonise Turkey.

The CHP's decision to declare İmamoğlu the party's candidate ahead of time caused alarm in the ruling party, and may have been a miscalculation on the part of Erdogan's opposition. Knowing that his political momentum would only grow in the years leading up to the 2028 elections, the AKP has acted quickly and aggressively. But their decision to act now, before İmamoğlu could consolidate his support, is also a sign of weakness, revealing the extent to which they fear his candidacy.

But the elimination of the mayor of Istanbul three years before the elections could also have the consequence that the public reaction against the decision will be diluted over time and eventually disappear. Public resentment is now at its peak. If the elections were held next month, or even in six months' time, Imamoglu would win a landslide victory. However, although public anger and its support for Imamoglu may be a source of short-term problems for the AKP, with three more years to go, the hope is that it will dissipate over time.

Once again Erdogan has shown himself to be a bold and calculating politician, well aware of his surroundings and internal dynamics. However, his gamble is not without risk, because if the protests get out of hand, or even worse, if they are repressed, then everything could become unpredictable, because excessive violence, together with the serious economic situation affecting the most humble strata of a country where the middle class practically does not exist, could give rise to an unprecedented social explosion. And of course, in the current context, the destabilisation of a country like Turkey could provoke a chain reaction that brings us even closer to the perfect storm.

As we mentioned a few weeks ago, we are living in ‘interesting times’.

[i] De la Corte Ibañez, Luis ‘Historia de la Yihad’, Ed Catarata, 2021