Journalistic Orientalism: When Le Monde Reinvented Morocco

- Exoticism and fidelity to reality

- Direct observations and precision

- Reproduction of Orientalist discourse

- Media Orientalism

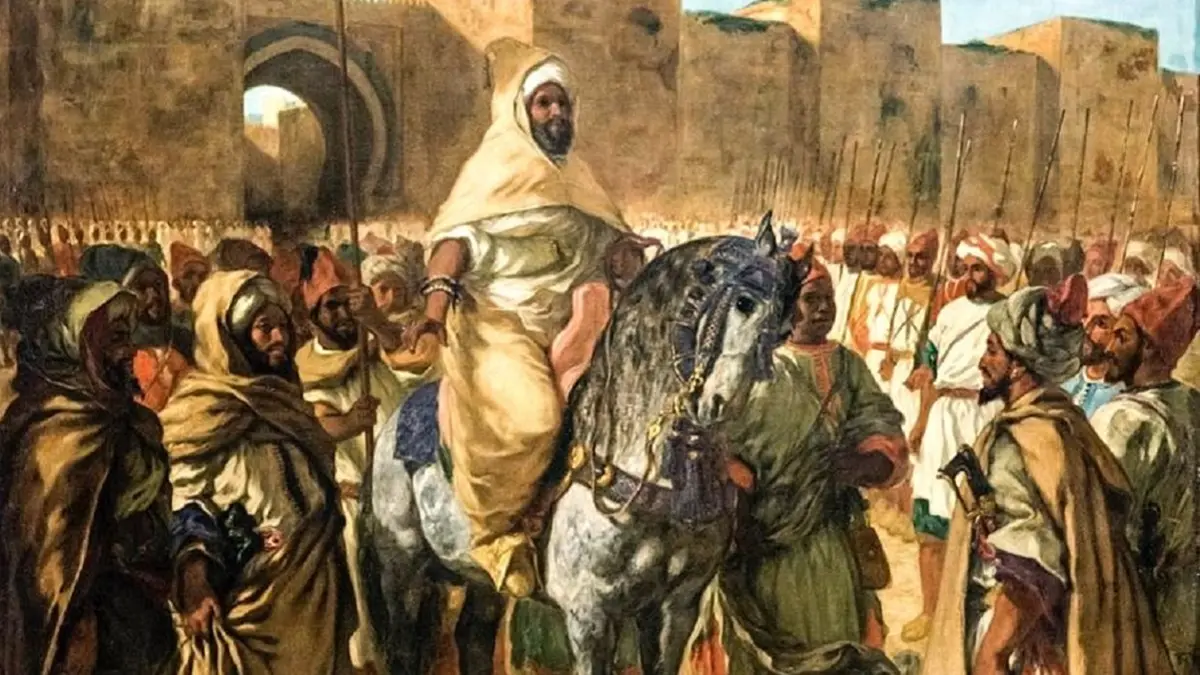

The first is that of Sultan Mulay Abderrahmane, proudly emerging from his palace, mounted on his horse, dressed in a gold and white costume, surrounded by his guard and his principal officers, as immortalised by the brush of Eugène Delacroix. The second image refers to Sultan Mulay Hassan I, as recounted by British journalist Walter Harris in his work Morocco Vanished, when he writes:

"It was in 1887 that I first entered the Moroccan court, only a few months after my arrival in Morocco, following an invitation from the late Sir William Kirby Green to participate in his embassy to the Sultan. Mulay Hassan was then at the height of his power. He was a strong, sometimes cruel and undoubtedly capable ruler. His energy never faltered; he maintained order among the rebellious tribes and constantly suppressed uprisings, travelling tirelessly throughout the country, always accompanied by his multitude of harkas."

These two images, full of rigour and precision, which present the two powerful Commanders of the Faithful and Heads of State in all their majesty, contrast sharply with the vague, fanciful and misleading portrait that the newspaper Le Monde attempts to paint in its so-called investigation. These two deeply divergent representations of monarchical power in Morocco seem to reflect the gap between two Orientalist sensibilities: one classical, enlightened and based on a sincere and authentic concern for reality; the other modern, erroneous and marked by a media drift devoid of any scruples towards the truth.

Eugène Delacroix depicted Sultan Mulay Abderrahmane of Morocco in a famous painting made in 1845 entitled ‘Mulay Abderrahmane, Sultan of Morocco’. This work shows the sultan leaving his palace in Meknes, in a majestic and imposing posture, embodying both the power and dignity of the sultan. Delacroix captures a fascinating moment in an impressive ceremony, where the sovereign is shown in a solemn setting, as an iconic figure of monarchical power in Morocco. This image, although imbued with an artistic style rooted in the tradition of classical Orientalism, highlights both the sultan's direct authority and his connection to an ancient tradition. This painting, preserved in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, is historically linked to a French diplomatic mission led by the Comte de Mornay, in which Delacroix accompanied the delegation as a painter and witness.

Exoticism and fidelity to reality

In this representation, the sultan appears on horseback, a rule among Alawite sultans for giving audiences, gazing towards the horizon, a symbol of his authority and vigilance over his kingdom. The details of the setting and the key figures of the Majzén reinforce the impression of a well-established and respected power. In this work, Delacroix combines the documentary precision acquired during his trip with a romantic and Orientalist vision of the grandeur of the Moroccan sovereign, making this portrait a major reference point for pictorial Orientalism.

It is fair to say that pictorial Orientalism, despite its marked exoticism and its tendency to convey an essentialist vision of the East, also had the merit of presenting a certain fidelity to reality and a capacity for ethnographic understanding, qualities that are sorely lacking in certain forms of contemporary journalistic Orientalism. In fact, from the mid-19th century onwards, some Orientalist painters became true travellers and meticulous observers, carrying sketchbooks, collecting objects and inscribing their works in an aesthetic approach that was often faithful to what they had seen in the field. This formal fidelity to material and cultural reality is expressed in the detailed representation of costumes, landscapes, architecture, as well as social and political customs.

However, this visual accuracy is often accompanied by an adapted interpretation, shaped to meet Western expectations, emphasising fantasies of leisure and sensuality, which produces a dreamlike and sometimes stereotypical image of the Orient. Nevertheless, the attitude of certain artists at the end of the 19th century was oriented towards an ‘ethnographic realism’ in which the representation of the East became more scientific and documented, with the aim of bearing witness to real life and Eastern customs. Thus, pictorial Orientalism oscillates between exoticism and attempts at objectivity, contributing both to the construction of a Western imaginary and to the enrichment of a more documented view of the Orient.

In ‘El Marruecos desaparecido’ (The Disappeared Morocco), Walter Harris develops a vision of Morocco at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries that is both historical and tinged with colonial Orientalism. His work recounts a bygone era in Morocco before and during the turbulent times of the French protectorate, highlighting the political tensions, power struggles and complex relationships between the majzen, the tribes, the chorfas and the religious brotherhoods. His perspective shows a Morocco in profound transformation, where traditional structures are slowly fading away in a context of decline of an old order mixed with the rise of European domination. Thus, Harris paints a kind of nostalgic and critical portrait of a ‘Morocco of yesteryear’ given over to the mutations and upheavals of its time.

Direct observations and precision

Walter Harris, like Eugène Delacroix, demonstrates in his writings a marked concern for precision and direct observation of the terrain. As a British journalist and correspondent, Harris lived in Morocco for several years and had privileged access to the Moroccan court, which allowed him to offer accurate and detailed descriptions of the country's political and social realities. Unlike some journalists caught up in an ignorant and arrogant orientalism, Harris adopted the stance of an attentive and often critical observer, seeking to describe the power of Sultan Mulay Hassan with a mixture of admiration for his energy and lucidity in the face of his cruelty. He highlights his role in maintaining order in a context marked by anarchy and constant rebellions, meticulously describing the movements of the Sultan and his military cohort.

This approach testifies to a desire to faithfully reflect the complexity of Morocco at the time, through direct and concrete observations, comparable to Delacroix's ethnographically precise pictorial method in his portrait of Sultan Mulay Abderrahman. Harris thus combines journalistic rigour with a keen sense of detail in the field, which reinforces the historical and documentary value of his work.

Despite a certain Orientalist inspiration typical of his time, Walter Harris does not allow himself to be confined by essentialist stereotypes or a simple taste for exoticism, preferring a perspective based on lived experience, direct observations and a keen sense of political complexity. His work ‘El Marruecos desaparecido’ (Morocco Disappeared) is certainly part of colonial and Orientalist literature, but it offers detailed, accurate and documented descriptions of Moroccan realities.

Reproduction of Orientalist discourse

Orientalist discourse as an essentialist ideology has never really disappeared from the political scene and the mainstream Western media; it is constantly reproduced in various forms and with varying intensity depending on the period. Through contemporary information and entertainment media, Orientalist clichés about the Arab world perpetuate a distorted image of the ‘Other’, reinforced by erroneous and substantialist cultural representations.

This modern Orientalism no longer responds solely to curiosity or artistic, scientific or media interest, but, as Edward Said, the founding theorist of postcolonial studies, pointed out, is an ideological tool that serves to justify power relations and maintain Western cultural and political domination. Thus, these media representations often contribute to the dehumanisation, marginalisation or caricaturisation of the peoples concerned, obscuring their complex social, political and cultural realities.

It is in this continuity of Orientalist discourse that a number of Western journalists today write about North Africa and the East based on clichés and stereotypes without any respect for professional ethics, which corresponds to what can be called “media Orientalism”, a phenomenon characterised by a simplistic, essentialist and often biased reproduction of the societies of these regions, perpetuating fixed and negative representations inherited from colonial and imperialist discourse.

Media Orientalism

If it was not this negative and substantialist view, saturated with fake news, simplistic judgements and slander, that presided over the supposed investigation by the newspaper Le Monde into the reign of Mohammed VI, how can we explain that this widely read media outlet could have strayed so far from all journalistic and ethical rigour?

From the perspective of journalistic Orientalism, as a system of representation and thought that continues to shape the Western perception of the Other (the East and North Africa) through an often dismissive and unquestioning view, the daily newspaper Le Monde represents a typical example which, through a series of sensationalist and controversial articles written to the detriment of the tradition of rigorous investigative journalism, illustrates how an influential media outlet can perpetuate an Orientalist vision that conveys stigmatising and derogatory stereotypes about the Other. Thus, France's leading newspaper contributes to keeping alive an Orientalist imaginary, built around a large North African country, while feeding a fabrication of reductive and erroneous perceptions about the Moroccan monarchy.