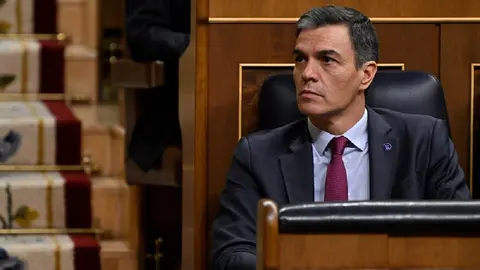

Pedro Sánchez, Yolanda Díaz and the rabbit in the hat

The audience in the hall knows that the hat is not empty, that there is a rabbit inside, that sooner or later, it matters little, but that it is there. The conjurer tries to make believe that the hat is clean, that there is nothing, but the expectant agora knows that he is dissimulating. It doesn't matter, because the power of the magic is such that everyone, young and old, awaits the climax when the immaculate gazap will emerge from the hat, white and glistening.

In politics the same thing sometimes happens, but not always. Pedro Sánchez, who has been in the Moncloa for five and a half years now, and who leads his party, the PSOE, with an iron fist, made Spaniards believe that Yolanda Díaz, the trade unionist and labour lawyer - of the former she worked, of the latter little -, a specialist in navigating all the acronyms of radical observance, who was not in her ranks, who went her own way, was in no way hiding in the socialist hat.

And unlike the public towards the conjurer, the Spaniards did believe him, starting with the miscellany that emerged in the heat of the Iberian spring of 15 May 2011, which gave rise to the Podemos movement, and the various Mareas and Comunes across the country. And when the vedette announced with a smile on her face that she was going to create a new party, they went after her as if she were the pied piper.

However, there are many who think that the dapper figurine has been hidden in Pedro Sánchez's hat for several years. It is not true that SUMAR and PSOE have taken months to draw up what they have presented as the coalition's programme; it is not true that there are abysmal differences between the two figures; nor is it true that, at times, even in the sessions of the Council of Ministers, they have been on the verge of breaking the deck. This is all part of the theatrical staging, like that of the conjurer when he prepares the suspense of the rabbit.

Pedro Sánchez and Yolanda Díaz have always agreed on the fundamentals. "Operation Chistera" was aimed at sinking the Podemos movement and winning back the voters that the PSOE has always believed belonged to it by historical right. The creation of SUMAR, bringing together twenty political formations at state and regional level, has been aimed at dynamiting the assemblyist party that emerged from 15M, which possessed the legitimacy of the support of millions of young and not so young people. It still has some of it left, although less. SUMAR has no legitimacy or historical trajectory, it is a cafeteria invention. Izquierda Unida did have trajectory, legality and legitimacy, but it allowed itself to be fobbed off with the Yolandist invention.

Now that the rabbit has come out of the hat and Yolanda is clearly presenting herself as "the left wing of the PSOE", the game is far from over. Because Díaz can only be sure that the 10 deputies of her obedient clan in the SUMAR bloc will follow her and vote for the investiture of the future PSOE centre-PSOE left government. Not so the five from Podemos, the five from the Comunes, the other five from Izquierda Unida and the remaining six from Más Madrid and other regional acronyms. In the ranks of the most veteran members of the 15M legacy, there is a feeling of having been deceived, manipulated. Some speak of "betrayal", but that is a big word.

Pedro Sánchez, then, has a problem; not only in taming independentistas, republicans and abertzales, but also among his own members of his past coalition government. And it is not certain that the talk of sumarísima will convince veteran preachers like Errejón, Belarra, Pisarello, Enrique Santiago and others to say "yes".