Don't miss the EU-Mercosur agreement train

We have alternated between phases of optimism and disillusionment when moments that promised the conclusion of the agreement were followed by disappointments caused by last-minute demands from both sides. All this had been going on for a quarter of a century, until 6 December 2024, when the negotiations were concluded and the hundreds of pages and annexes of the long-awaited and eagerly anticipated agreement were ready for final drafting.

The European Council was due to give its final approval last week in Brussels. This did not happen. The takeover of the Belgian capital by 15,000 European farmers, accompanied by hundreds of tractors, who erected barricades of animal excrement and scattered thousands of kilos of potatoes around the European institutions' premises, ultimately dissuaded the heads of state and government from ratifying the agreement with Mercosur.

France maintained its opposition, based on the ‘asymmetry of requirements and demands between agricultural and livestock products on either side of the Atlantic’. French President Emmanuel Macron secured Italy's decisive support for not signing the agreement. The Italian Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, was content with a postponement and made this known to her South American counterpart. Spurred on by his farmers, who in turn are leading the protest of their Spanish counterparts, Macron assured that France would not sign the agreement as it stands, aware that its farmers will continue to block the country's roads, motorways and railways, crushing tens of thousands of lorries, especially Spanish ones, which are powerless to prevent their perishable goods from spoiling.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz expressed his disagreement, seconded by Pedro Sánchez, both convinced that the overall benefit of the agreement for the EU outweighs the negative aspects of a less competitive European agriculture compared to the legumes, vegetables and meats of Mercosur.

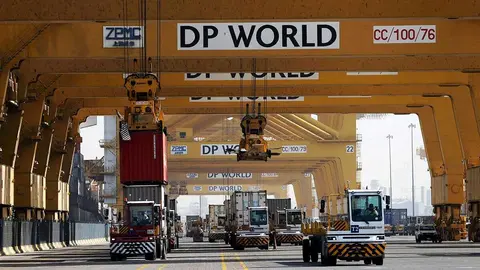

The agreement was scheduled to be ratified this past Saturday in Foz de Iguazú, on the Brazilian side of the impressive waterfalls, where the top leaders of the four countries that make up Mercosur gathered. All agreed that they would wait for the EU to iron out its internal differences, but agreed that in the meantime they had to send a ‘signal’ that they were in the process of agreeing similar pacts with other countries. If these agreements with other countries were to materialise, and without a response from Europe, it would be very difficult to maintain ‘exclusivity’, which could ultimately make the ratification and entry into force of the EU-Mercosur agreement impossible. Specifically, they cited the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, Indonesia and Malaysia as ‘alternative countries’, in addition to Vietnam, with whom they have announced that negotiations are already underway for a tariff preference agreement. The host of the meeting, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, said that Mercosur ‘has already made all possible concessions through diplomatic channels,’ hinting that if Europe does not accept the current terms, it would face much tougher negotiations.

The European Commission has reportedly committed in writing to signing the agreement definitively on 12 January, in Paraguay, the country that has taken over the rotating presidency of Mercosur. It is assumed that until then Giorgia Meloni could change the direction of her decisive vote in exchange for some small inter-European concessions. On the other hand, it seems much more difficult for Macron to change his vote, given the intransigence of French farmers. They, like their Spanish counterparts, would be the clear losers in the deal. But, as with any leap forward, there are always winners, in this case industry and services, and losers.

A hypothetical break between the two blocs, the EU and Mercosur, would not benefit the Ibero-American countries either. Argentinian President Javier Milei gave some clues when he attributed the postponement of the signing of the agreement with the EU to the ‘rigidity of Mercosur's rules’, which oblige the bloc's countries to negotiate trade agreements with third parties jointly, a way of warning that such an obligation could be blown up.

Milei, like his three colleagues in Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, surely had China and the United States in mind, especially the latter, as President Donald Trump is a staunch supporter of bilateral agreements