Former Tunisian president convicted before "correcting the ways of the revolution"

He was the first elected president in the history of Tunisia's democratic transition, once considered an example that raised high hopes that Arab countries would embrace a political and social model similar to the Europe of freedoms. Now, Moncef Markuki, who was Tunisia's head of state between December 2011 and December 2014, has been sentenced in rebellion to four years in prison "for endangering the security of the state".

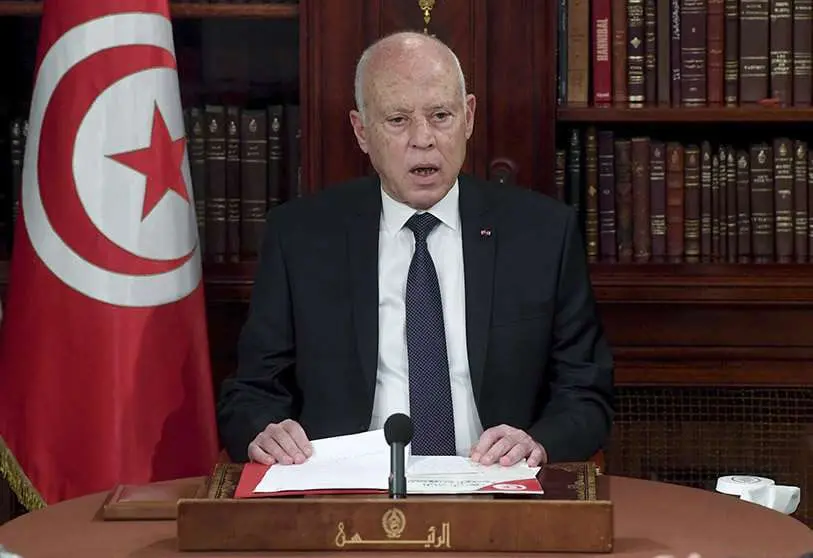

What was the offence for which he was sentenced? He took part in a demonstration in Paris in which he himself was particularly critical of the current Tunisian president, Kais Saied, whom he openly accuses of "clearly dictatorial behaviour" for having suspended the parliament and effectively arrogated to himself all legislative and executive powers.

Marzuki, who lives legally in the French capital, has been particularly critical of what he sees as the current president's 'totalitarian drift', and has gone so far as to call on the French government to reject its support for Saied. The hostility between Tunisia's current and former presidents reached its zenith when Saied dismissed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi last July, while issuing a decree suspending parliament indefinitely and his own assumption of all powers. "A classic coup d'état", Marzuki, who found himself stripped of his diplomatic passport, called it at the time, and decided to step up his critical activity on social media, where he says that "I keep telling Tunisia's friends and allies not to interfere in our affairs with any direct or indirect support for the coup, because it would be a stab in the back for democracy and the Tunisian people".

Marzuki had become an extremely uncomfortable enemy for President Kais Saied, who had already presented to the public his plan to "restore stability to the country", seriously threatened in his view by the continuing blockade of parliament and the ongoing demonstrations in the country's most important cities. The truth is that the main inspiration for the unrest and the resulting paralysis of the country were the Islamists of Ennahda, which in Arabic means renaissance, and which became Tunisia's main political force, impregnated of course with a strong religious component.

By dissolving the Parliament and assuming all powers, Saied declared the 2014 constitution 'defunct', which Islamists saw as a move to remove them from power, a claim that is likely to be true. It also seems to be true that the 2011 experiment did not go well, so that what is being proposed now is practically a return to the starting point.

President Kais Saied is going to begin this new journey with a massive popular and telematic consultation, theoretically aimed at all citizens, so that, through answers to supposedly very clear and concise questions, they can express what they want for the future of the country. A call that, in the president's own words, will be the first move "to correct the paths of the revolution and of history".

A group of experts, yet to be defined, will analyse the responses, the summary of which will be used to draft a new constitutional text, which will be submitted to a referendum on 25 July, six months before legislative elections are held on 17 December 2022 under the legal umbrella of the new Constitution.

A full decade on from the first revolution in Tunisia, which caused a chain reaction throughout North Africa, we are back to square one, although this time the people's spirits are far from the enthusiasm and excitement that presided over that movement, which put an end to dictatorships and caused a violent shock of instability throughout the southern Mediterranean region.