New Prime Minister in France, same debt

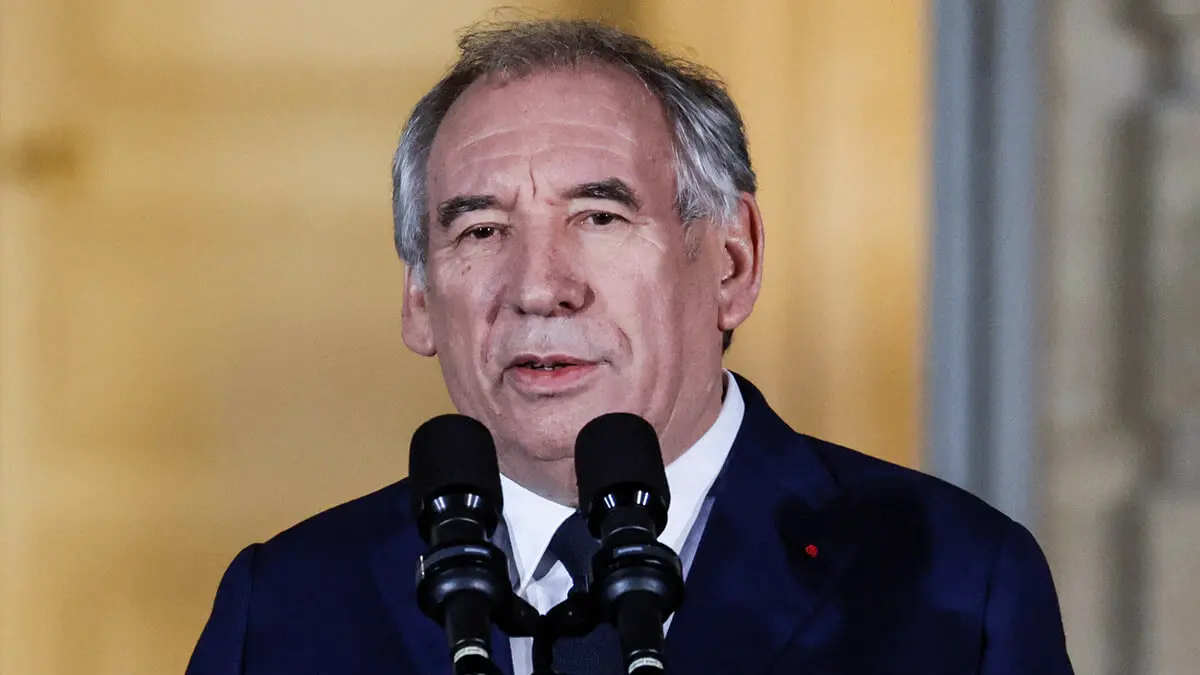

Not even a hint of euphoria. Almost at the same time that the centrist François Bayrou, 73, leader of the Democratic Movement (MoDem), took office as prime minister of France, the US agency Moody's gave him his first disappointment by downgrading the country's sovereign rating from Aa2 to Aa3 with a stable outlook.

Moody's, along with Standard & Poor's and Fitch (which had already anticipated downgrading France's debt), dictate the parameters accepted by the universal lending banks to determine how much and under what conditions loans can be granted to a given state.

The truth is that if the previous Prime Minister, Michel Barnier, did not manage to push through a budget that, between cuts and new taxes, managed to obtain 60 billion euros to cover the bulging deficit, the aforementioned agencies do not believe that François Bayrou will manage to do so either. Barnier was aiming for a public deficit of 6.1% of GDP by 2024, reducing it to 5% in 2025 and reaching the maximum 3% demanded by Brussels in 2029.

Moody's does not believe this and considers that France will not fall below 6.3% of GDP in 2025 and will stagnate at 5.2% in 2027. Far from reducing the 3.3 trillion euros of debt, which currently stands at 113.3% of GDP, the agency points out that by 2027 it will have risen to 120%.

With these figures, Bayrou, who has already stated that his priority is to reduce the deficit, is going to find it even more difficult to form a government in which, although he does not have any of the extremes that united to overthrow his predecessor - the extreme left of France Insoumise (LFI) and the extreme right of Rally Nationale (RN) - he will have to make quite a few contorting moves to marry the demands of the indispensable Socialist Party, now detached from the New Popular Front, and the conservatives of the Republicans (LR), who are no less necessary for the formation of a more or less viable government programme.

Bayrou, a perennial mayor of Pau, is an old rock of French politics, which he entered in 1979: three times Minister of Education, twice as a candidate for the Elysée, and always in the reserve as a consensus figure to make the leap to higher missions. He is one of the few political ‘friends’ of President Emmanuel Macron, if such a degree of trust is possible in politics. At least it is commonly believed that Bayrou is practically the only colleague who can speak clearly and without hot air to the president, and without fearing reprisals or any kind of animosity for telling him the truth.

It remains to be seen whether all the political and human capital accumulated to get the French National Assembly to abandon its cricket-cage state will be enough to get it to do so.

Meanwhile, the population is seeing its standard of living and its prospects of keeping its job deteriorate day by day, all this in the midst of unprecedented levels of growing insecurity. With the promise of the socialists and lepenists not to present him with a motion of censure for the time being on pins, his main mission is to achieve a budget that cannot be very different from the one that Barnier's was voted down. And so, at least until next summer, when it would be constitutionally possible to call new general elections. A not-so-distant date for which some parties are already calling for the introduction of reforms that, for example, would make up in a second round for the uncontested triumph of the NR in the first round.