The Tibet problem resurfaces

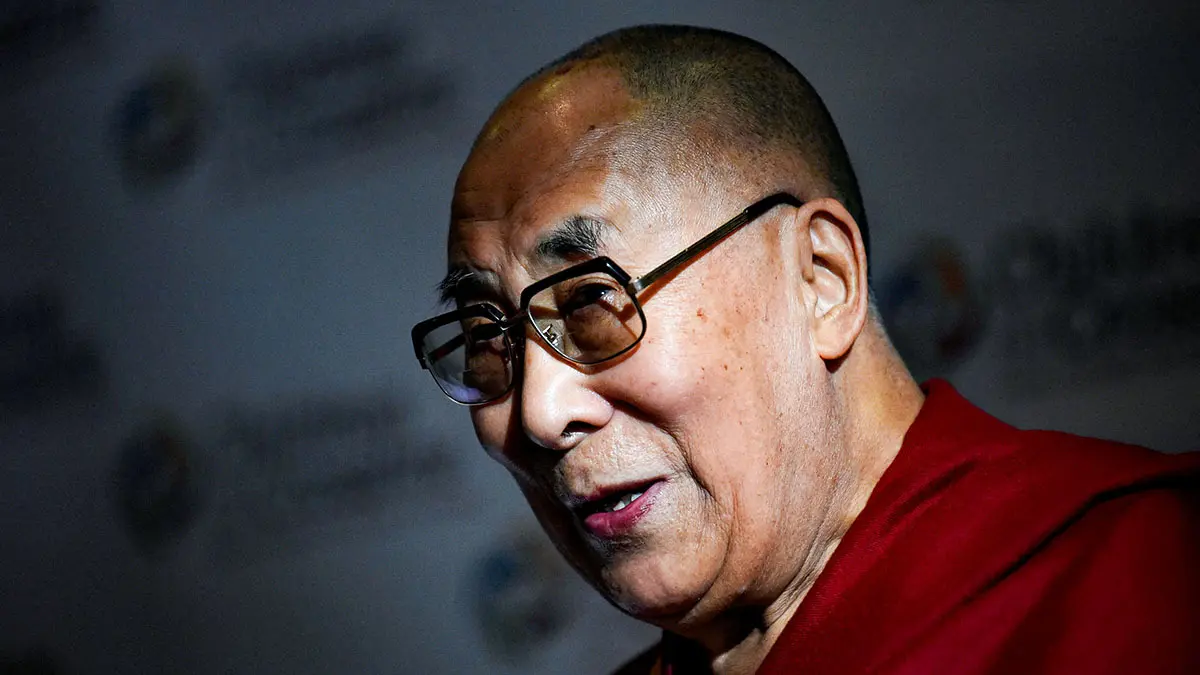

Annexed by Mao Tse Tung in 1950 under the pretext of liberating it from its feudal regime, its spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, has always maintained a political struggle with Beijing, which is now once again experiencing another crucial moment.

On the occasion of his 90th birthday on 6 July, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th spiritual and political leader of the Tibetans, has launched a new challenge to Chinese power by announcing that, after his death, ‘the institution of the Dalai Lama will continue, and it will be the Gaden Phodrang Trust, that is, his council of elders, which will identify his successor in accordance with the procedures of search and recognition in accordance with tradition’. This provision has a final clause of utmost importance: ‘No one else has the authority to interfere in this matter.’

With this categorical statement, the Dalai Lama opposes the manoeuvres that the Chinese Communist Party has been carrying out to appoint Tenzin Gyatso's successor, arguing that both he and the Panchen Lama, the second spiritual authority, must be chosen in accordance with 18th-century imperial rules and the ritual of the Golden Urn, an interpretation that the still Dalai Lama expressly rejects by adding that his successor ‘will be someone who must have been born in the free world’.

His Holiness, as the Dalai Lama is addressed by his devotees, recognised as the reincarnation of his predecessor when he was just two years old, fled Tibet when Chinese troops invaded the country in 1950, subjecting it to violent repression. The Dalai Lama took refuge in northern India, living his entire life in a monastery in McLeod Ganj, known as ‘Little Lhasa’, near the main town of Dharamsala.

In his latest statement, the Dalai Lama also urges his followers to reject any figure imposed by China, arguing that ‘the authentic reincarnation must be free from political manipulation and born in an environment where religious freedom is respected.’

The Tibetan community in exile fears that China will encourage internal divisions among the Tibetan people if, as expected, Beijing ends up appointing an alternative Dalai Lama. There is already a precedent in the form of the current Panchen Lama, who is loyal to the regime. In 1995, the Dalai Lama publicly recognised Ghedun Choekyi Nyima, then six years old, as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama. The Chinese regime immediately kidnapped him and has since kept him in an unknown location, while choosing Gyaltsen Norbu, who has always strictly followed the guidelines issued by Beijing.

Although China has made a significant investment effort to modernise Tibet, even providing it with the impressive tourist attraction that is the so-called Transtibetan or Cloud Train, the highest in the world, which connects Xining with Lhasa in 21 hours, it has not been able to eradicate the intense Buddhist spirituality of the Tibetans. It has therefore opted to ensure ideological control over the region and its religious institutions, trusting that the passage of time and the distancing of Tibetan Buddhist figures in exile would weaken resistance.

Furthermore, given the protection that India has offered the Dalai Lama and his governing council for seven decades, this issue could also be a source of tension between the two major powers in Asia.

Furthermore, Tibet, a region two and a half times the size of the Iberian Peninsula, is the continent's largest plateau and the source of the main waterways of the Himalayan mountain range, which are increasingly vital for supplying both the intensive agriculture of China and India and a large part of their huge populations. It is therefore also a natural treasure that would be a source of dispute if global warming were to substantially reduce the water supply from the Himalayan mountains.