Duel of the titans in the "backyard" of the United States

As much as, to paraphrase Alfred North Whitehead, it seems that the episodes of Donald Trump's presidency will eventually be considered as mere footnotes in the book of American history, it is likely that his name will be associated with the moment when America chose to make a virtue of necessity, after noting the difficulty of continuing to be the dominant economic player in Latin America and the cost of sustaining in the long term the strategic control the United States has had in the region since the enactment of the Roosevelt Corollary in 1904, which gave a charter to the Monroe Doctrine.

Washington's policy of "regime change", in which it has been known as its "backyard" since the beginning of the 20th century, has taken the form of bloody and bloodless interventions in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Chile, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela, supporting governments and political factions with economic, security and foreign policy interests of the United States.

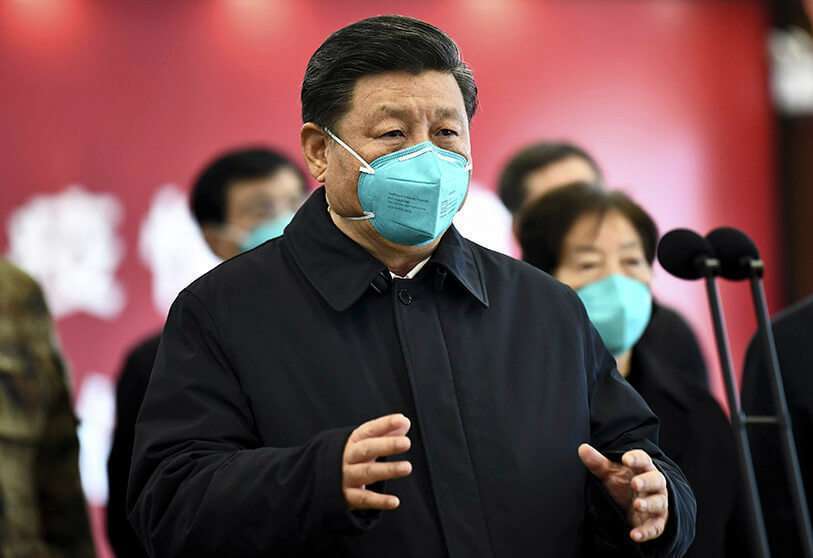

As a result of these policies, America's economic hegemony in Latin America had never been disputed in over a hundred years. In 2017 the situation became less clear, with Panama joining the Belt and Road Initiative promoted by China, which quickly spread to Trinidad and Tobago, Bolivia, Guyana, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Grenada, El Salvador, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Ecuador, while Barbados, Jamaica, Peru and Argentina. With the pace of change, and despite Trump's lack of rhetoric about the region, when he witnessed the relative decline of China's progress, the State Department set to work on developing a continent-wide initiative designed to counteract China's growing influence, known as "America Grows"; a programme of private investment in infrastructure and energy which was soon joined by Argentina, Chile, Jamaica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil, El Salvador, Honduras and Boliva, while Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua were explicitly excluded from the programme. "America Grows" is a corrected and expanded version of the "Partnership for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle", a plan whose investments, through the Inter-American Development Bank, produced meagre results.

From a geopolitical perspective, while China has prioritised its presence in South America, the US is focusing on Central America, under the premises of the "Caribbean 2020" plan, something that is not unrelated to migratory pressure and drug trafficking towards North America. These compartmentalisations will make it very difficult for investments in infrastructure to be carried out not with criteria of collaboration, but with the vision of strategic unity that suits Ibero-America.

On the contrary, the rivalry between the two giants and the zero-sum mentality they both display may end up benefiting the investment banks of both countries more than the population of the Ibero-American states. Indeed, some macro-projects such as the Central Bi-Oceanic Railway Corridor-which is expected to run for over 3,800 km to link Brazil, Bolivia and Peru-have already been negatively affected by China's participation.

One of the reasons for the incompatibility between the two initiatives is that the modus operandi of the two titans is radically different: While China cares more about mice than about the colour of cats, and does not make its investments conditional on political reforms that question the legitimacy of the established power, the United States operates through memoranda of understanding that oblige the signatory states to change their regulatory frameworks and tendering processes, increasing transparency and good practices, effectively implementing US standards in third countries, This ultimately puts sticks in the wheels of the agreements with China, while facilitating tenders with US companies, which by definition comply with US regulations, especially after the enactment of the "BUILD Act" of 2019, which encourages US private sector investment in Latin American countries, de facto encouraging US disinvestment in Chinese territory.

What China and North America do agree on is prioritising investment in infrastructure related to the extractive industry, though China has opened up another front in the field of telecommunications, where it has a technological advantage in 5G and high-voltage networks, from which it benefits by transferring industrial resources through the China-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States Fund. Some estimates indicate that the region has a deficit of some 500 billion euros in the sectors on which the Americans and Chinese have set their sights. This suggests that investments of around 7 per cent of GDP, sustained over decades, are needed to subvert these shortcomings that are hampering Ibero-American progress.

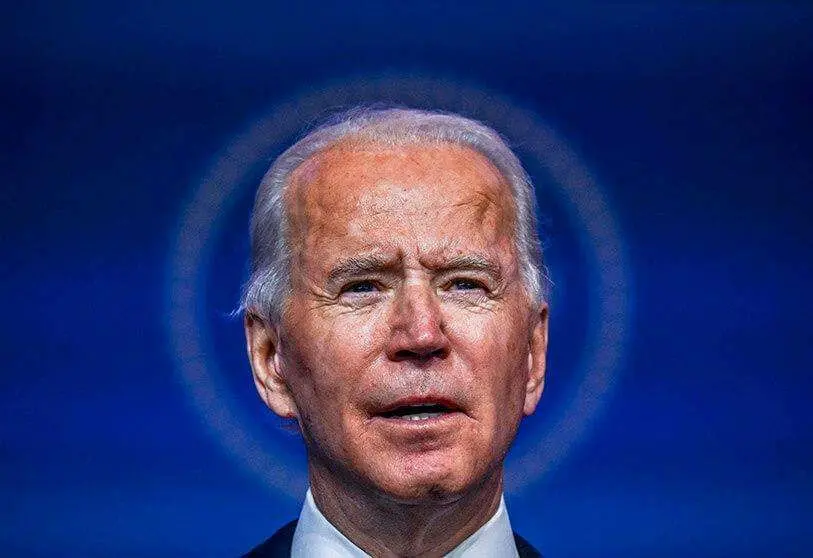

Given the cross-cutting nature and weight of the interests at stake, it is quite implausible that Joe Biden's new administration should substantially alter the course of the surreptitious interventionism that lies beneath the surface of the "America Grows" plan, just as it is implausible that China should desist from its efforts to invest in creating new markets for its products in Ibero-America. It is therefore to be expected that friction between the two giants will have repercussions on the region's national policies.

One of the countries whose medium-term situation may serve as a thermometer of the state of Ibero-American geopolitics is Chile, which is currently undergoing a constitutional reform process. One of its objectives is to amend the rights to exploit natural resources, particularly water resources, a strategic element for the extractive industry, the main beneficiary of the liberalisation promoted by Pinochet, from which an economic ecosystem has emerged in which politics and business often overlap.

China is struggling to make a place for itself in the Chilean economy, a market whose main investors are Spain, the US and Canada. Recently, China acquired 24% of Chile's Sociedad Química y Minera, and 27% of the energy distributor Transelec. Paradoxically, these investments have been possible because China has benefited from the regulatory laxity that has historically favoured North American companies in Chile, so that, a priori, it has no incentives to support a new constitution that would restrict its investment capacity and limit the environmental impact of the businesses it controls.

On the contrary, the United States is interested in precisely the opposite, as can be inferred from the text of the memorandum of understanding signed between "América Crece" and the Chilean authorities, which was drawn up to avoid parliamentary scrutiny. Chile is scheduled to hold a referendum on the ratification of the new constitution in mid-2022. What happens in the Andean country during this interim period will be a good indicator of how this unprecedented duel of the titans in the "backyard" of the United States of America evolves.