The new Peruvian scenario: hopes and fears

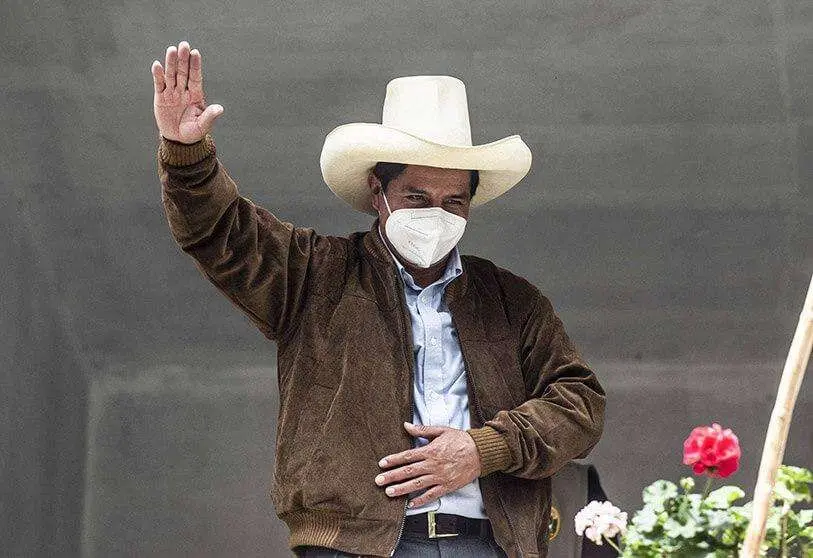

The victory by just a quarter of a point - not even half plus one of the votes - of Pedro Castillo over Keiko Fujimori has created an unprecedented situation in Peru, characterised by the rise of an anti-capitalist left-wing platform, precisely when the country had begun to reap, before the pandemic, the fruits of the economic liberalisation that has placed Peru among the most advanced economies in Latin America, thanks to the collective effort to overcome the years of leadenness of Abimael Gúzman's Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path). The statistics speak for themselves; the poverty rate has fallen from 60% in the 1990s to 21% today, while inequality has fallen 13 points over the same period, thanks to a 60% increase in GDP, a 78% reduction in malnutrition, and a 10-year increase in life expectancy. These figures are endorsed by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America, which predicts that Peru will be the country in the region with the highest economic growth in 2021, at around 9.5%.

However, this progress has not been accompanied by a reform of the political system, and Peru suffers from a fragmented and weak party system, which hinders governability and gives rise to uncertainty derived from the perennial conflicts between the executive and a frequently obstructive legislature.

Castillo's rise to power thus leads one to wonder what it is that his triumph at the ballot box addresses. He certainly lacks sufficient parliamentary support to turn the political system around, however much he persists in pushing for a Constitutional Assembly that puts him on a collision course with Congress without having an undisputed mandate to undertake such a process. Castillo must have understood on election day that the only way to implement part of his redistributive programme is through social democracy, not communism. Or, in other words, the path of evolution, not revolution.

Probably because he himself has reached this conclusion, Castillo has moderated his maximalist rhetoric, and has made gestures to send a signal of stability and legal security to the Peruvian and international business world, incorporating personalities such as Pedro Francke and Oscar Dancourt into his economic team, Socorro Heysen is expected to continue as head of the Superintendency of Banking and Insurance and Julio Velarde as president of the Central Reserve Bank, while the weight of someone as openly in favour of dialogue with sectors of the Peruvian establishment and gradualism in fiscal policies as Verónika Mendoza should not be underestimated.

All these people are solvent technocrats perfectly aware that the Peruvian economy cannot afford capital outflows or a credit rating downgrade that would exacerbate the exchange rate disparity between the sol and the dollar, something that the Peruvian banking system could hardly withstand. We should therefore pay more attention to deeds than words, no matter how inflammatory the rhetoric coming from Castillo's entourage, who will be forced to channel the expectations of the most radical elements of this cohabitation of government, such as Hector Béjar and Vladimir Cerrón, both very close to Castroism and with notable influence over Guido Bellido, the brand-new Cuban prime minister, into the realm of possibilism. It is from this perspective that Peru's exit from the Lima Group can be interpreted, a gesture that is more symbolic than substantial, given the meagre results achieved by this international alliance in resolving the Venezuelan situation.

In any case, Peru, like most Latin American countries, is going through a serious social crisis as a consequence of the pandemic, which has resulted in ten million Peruvians living on less than 100 euros a month, in a labour market in which underground and precarious jobs provide employment for 80 per cent of the population. The particularity of Peru is the structural dichotomy between the rural and urban worlds, with a poverty differential of 35 points to the detriment of the population of the interior. The risks of this social powder keg exploding are so obvious that even Roque Benavides Ganoza, Peru's leading mining magnate, has expressed his willingness to support the increase in mining taxes advocated by the new cabinet.

All in all, Castillo's victory has bought the country time by averting for the moment the danger of popular revolts driven by the radical left, something that would hardly have been avoided had Keiko Fujimori won. By not giving anyone an overwhelming majority, the Peruvian electorate has sent a clear message to the polls: understand each other.