Adam Michnik regrets that Europe lacks a great leader

Adam Michnik's (Warsaw, 1946) relationship with Spain dates back to the 1980s. A leader of the Polish dissident movement, he was a member of the Round Table that in 1989 decided on a transition similar to the Spanish one, so that the communist regime would step aside and make way for democracy.

Michnik was one of the great supporters of the transition model in Spain and a tireless advocate of a Europe that would take on and help the countries that had suffered the relentless rigours of Soviet communism to integrate into the Western model.

Often invited by the Association of European Journalists, he was also one of the regular speakers at the Menéndez Pelayo University in Santander for an annual seminar on Central Europe, which soon became a classic.

The creator and editor of Gazeta Wyborcza, the newspaper he turned into the most influential in Poland, he acknowledges that he learned and took many examples from El País, from which he now hopes to ‘get back on the right track’. Although he displays his tenacity and the same desire as ever to fight for the consolidation of democracy in Europe, he recognises that the EU, this Europe, has too many enemies who want to destroy it: ‘Russia wants to take over Ukraine; Trump has never liked the democratic model of Europe..., and we also have within us quite a few underminers of the project of European construction: Orban, Salvini, Le Pen, all of them financed by the Russian secret services of Vladimir Putin’.

Michnik considers the left-right debate to be outdated, and believes that the situation is dangerously similar to that of the 30s of the last century. ‘Then the antagonism was either with Adolf Hitler or against him. Today, the confrontation is between those who defend liberal constitutional democracy and those who want to destroy it’.

He believes, therefore, that Europe is already fighting a war, and that it would therefore do well to replicate now the same bloc that was assembled in the UK in World War II, when Labour and Conservatives joined forces to preserve democracy. ‘The problem,’ he stresses, ‘is that today we lack a great leader like the giants that emerged then, Churchill, De Gaulle, Adenauer...’.

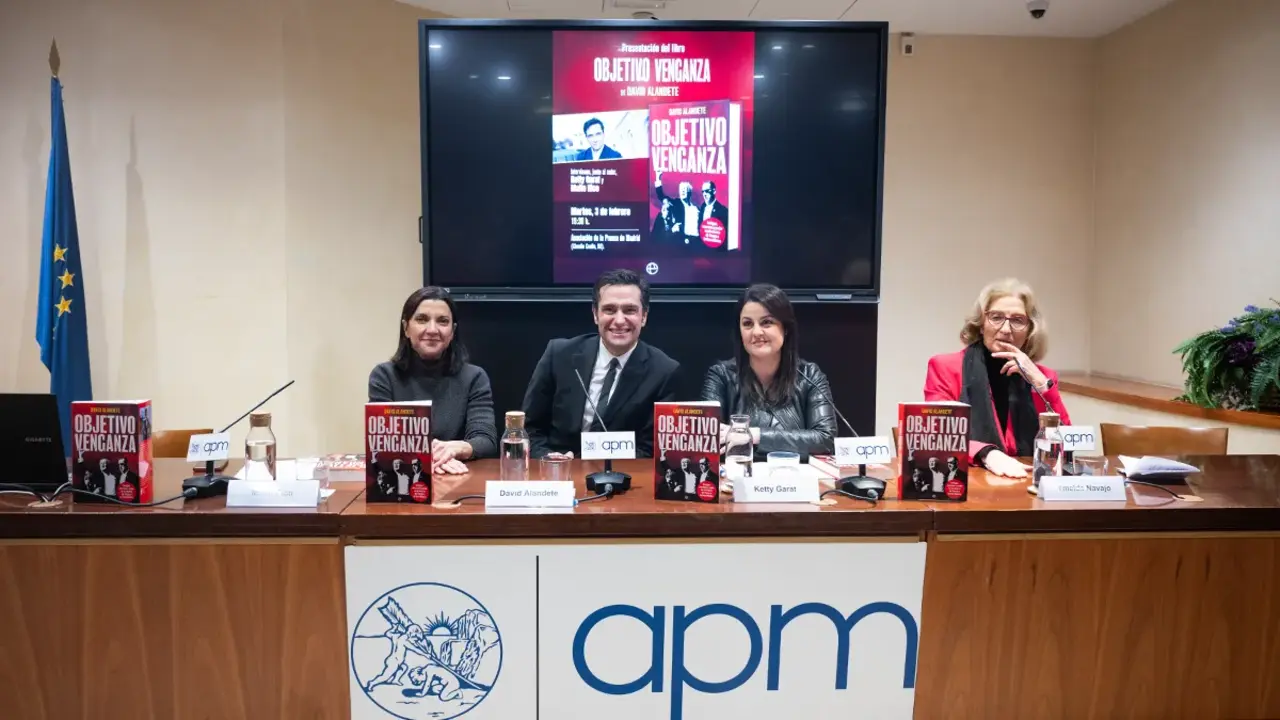

In the open conversation that Michnik holds at the APE's Madrid headquarters, the Polish opinion leader certifies that ‘social democracy is dead... of success, since its objectives have been adopted and assimilated by all’. And, in his opinion, that same social democracy, lacking new and ambitious universal goals, has dedicated itself to perverting the language, which it has turned into the language of a sect. ‘Let us not allow this perversion of language to take hold,’ Michnik cries, quoting George Orwell.

The author also revolts against those who want to rewrite history. He cites Rodríguez Zapatero, who wants to win the lost Spanish Civil War, but also those who try similar manoeuvres in Poland with regard to its 1921 Constitution or in the United States with regard to the Civil War. ‘There is a strong tendency to falsify the historical reality of countries’. In his opinion, this provides the basis for justifying current claims. And in this respect, he points out with his characteristic dialectical brutality that ‘the concessions to Catalonia and the Basque Country will lead not only Spain as a whole, but also both regions to catastrophe’.

Michnik, winner of the Robert Kennedy Prize, the Erasmus Prize and the Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities, defends the Spanish Constitution of 1978 as ‘the great example of how to deal with differences’, while emphasising how PSOE and PP always settled their disagreements within the Constitution. ‘Now I see that there are political forces that transgress the country's fundamental rule’.

Of course, he vindicates the figure of the leader of the Solidarity trade union, Lech Walesa, whom he describes as ‘a myth similar to St. George slaying the dragon’. He says it is undeniable that Walesa changed the course of history, but he is not shy about saying that ‘Walesa was not a good president; successfully leading a large, indefinite general strike with millions of followers does not make you a good president of the nation’. Michnik recounts that it took Walesa a long time to come to terms with it when he was no longer president. ‘He was surprised that the phone was no longer ringing, even though he himself had no one to call...’.

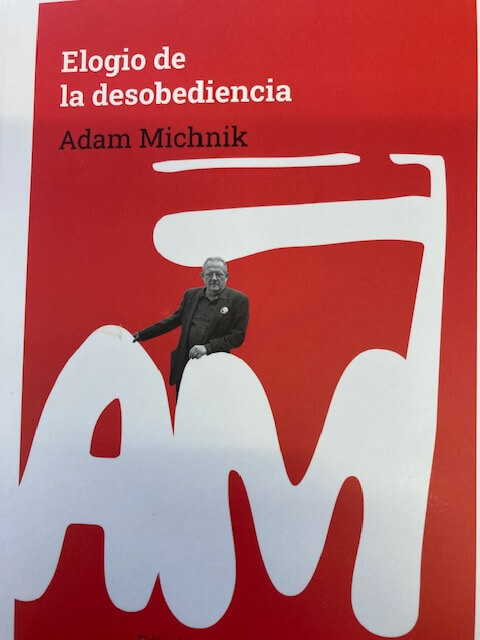

This anthology, entitled ‘In Praise of Disobedience’ (Ed. Ladera Norte, 247 pp.) closes with an epitaph to Aleksiey Navalny, the ‘heroic democrat who gave Russia his talent, his passion and his courageous heart, in short, his life’. Michnik sees him as a victim of Putin's war against civil society in Russia. ‘For we must remember that Putin's criminal invasion of Ukraine was preceded by his aggression against Russian society, independent of power, against that Russia which is being murdered, outraged and imprisoned’.