Catching the spirit... with no ulterior motives

The North American Consuelo Kanaga (1894-1978) ‘was the first press photographer, a person far ahead of her time’. This is how her friend and fellow photographer Dorothea Lange defined her. Like Imogen Cunningham, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Alma Lavenson, Tina Modotti and Eiko Yamazawa, she sought advice and professional help in a society in which it was already difficult for blacks, but even more so if you added the fact that you were a woman.

Kanaga is considered a pioneer of photojournalism, giving her graphic documents for the San Francisco Chronicle and the Daily News from 1915 onwards a broader content than the merely testimonial.

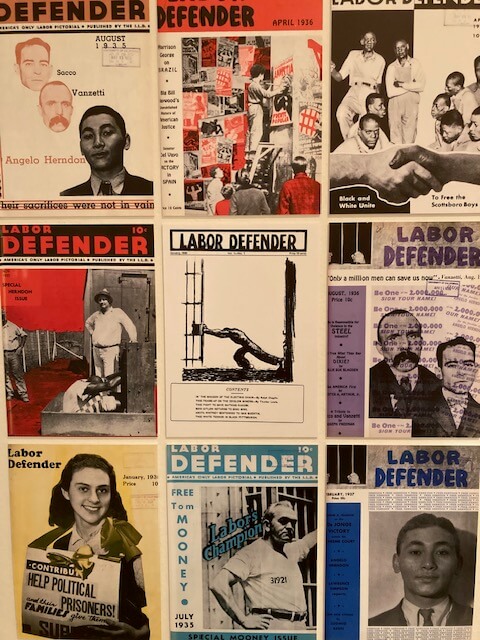

In the United States, in response to the prevailing racism, magazines and novels created by black men and women began to appear in cities such as San Francisco, Washington and New York at the end of the 19th century. This literary boom was the precedent for what is known as the ‘New Negro’ movement, which emerged in Harlem, New York, between 1920 and 1930, and which also gave its name to the most complete anthology on this cultural current, written by Alain Locke, considered at the time to be ‘the foundation of the black canon’. Kanaga was linked to it through his personal relationships and his photographic work, calling for a redefinition of African-American identity.

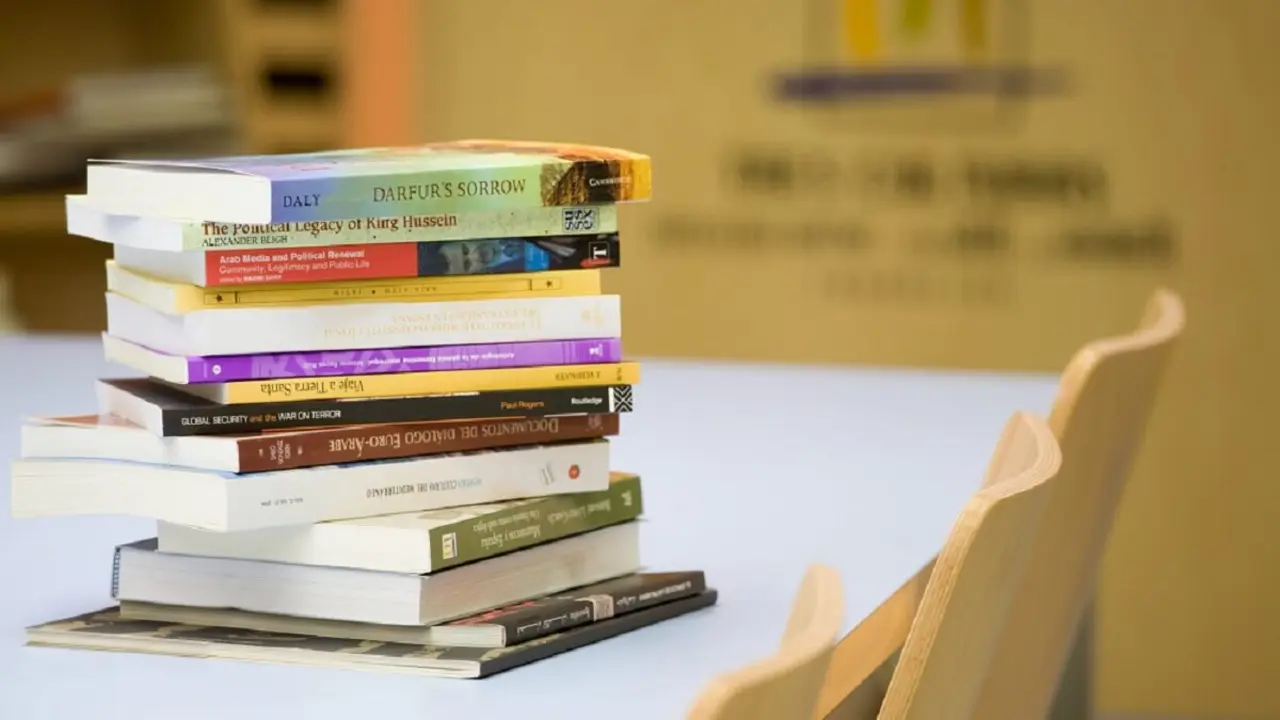

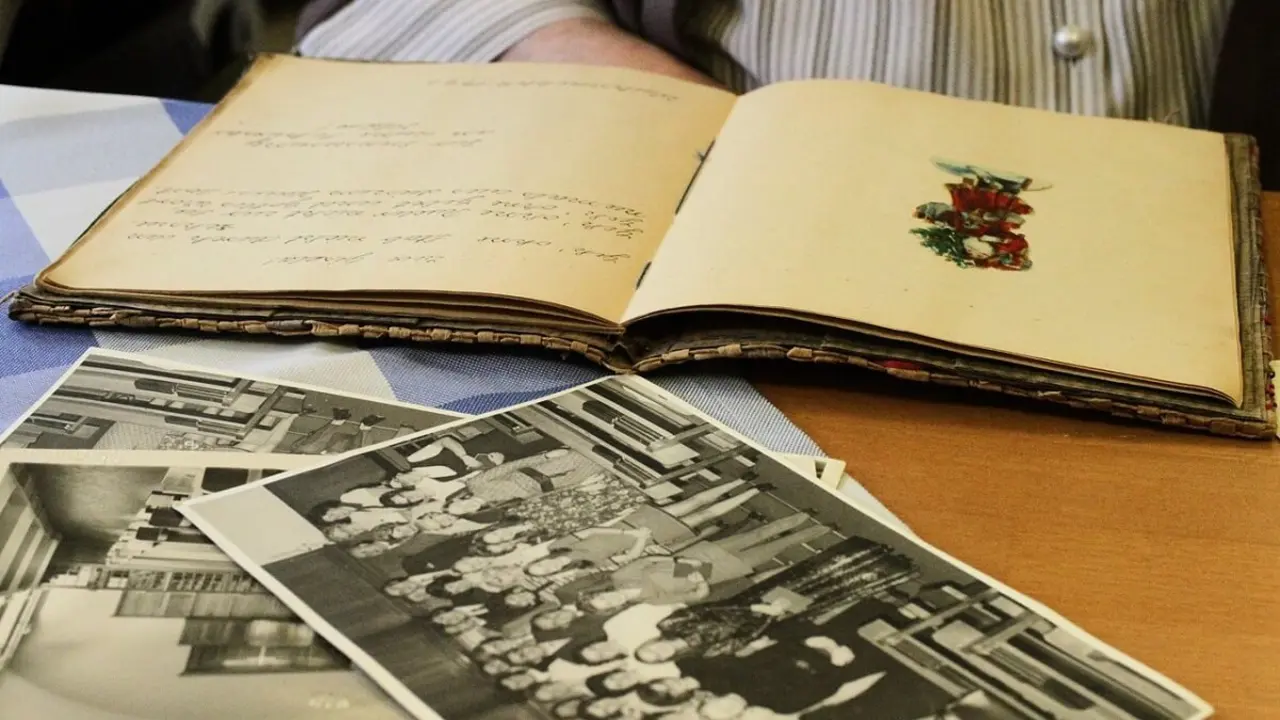

Her exhibition at the Mapfre Foundation in Madrid, entitled ‘Consuelo Kanaga: Catching the Spirit’, traces the six decades of this fundamental figure in the history of modern photography. Organised on the basis of the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, which has ensured the conservation of its archive, its curator, Drew Sawyer, has selected 180 photographs and diverse documentary material. While tracing and contextualising Kanaga's work and presenting some of his iconic images, it also focuses on the role of photography in the representation of the African-American world, with a splendid gallery of portraits and a good sample of what has come to be called working-class photography.

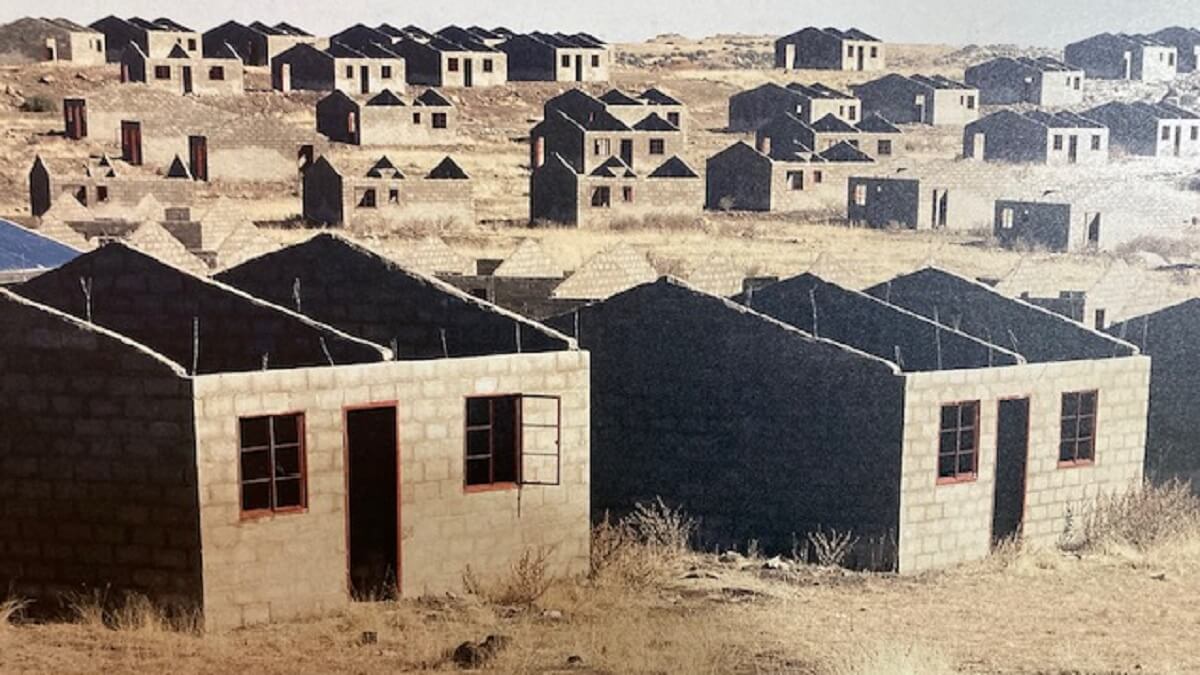

At the same time, the Foundation is also presenting a major exhibition of the South African David Goldblatt (1930-2018), who devoted his entire life to documenting his country and its people. Known for his subtle portraits of life under apartheid, the total segregation by race, his work, with its wide thematic diversity, is today essential for understanding what is undoubtedly one of the most painful processes and periods in contemporary history.

The grandson of Lithuanian Jewish refugees, David Goldblatt was the first South African to have a solo exhibition at MoMA in New York, and is recognised as a major artist by Germany, France, the USA and his own country, South Africa.

The exhibition highlights one of his most appreciated qualities, the apparent tranquillity of his images. Goldblatt fled from the more lurid aspects that were produced every day under the apartheid regime. And so, in this depiction of everyday life ‘where nothing was happening’, the viewer was encouraged to draw his or her own conclusions. The content was implicit in the apparent tranquillity and the very precise captions accompanying the image, showing the daily manifestations of racism, as well as the economic, social and political plunder of the black population under white rule.

Certainly, Gooldblatt's status as a white man allowed him greater freedom of movement. In the early 1970s, he published an advertisement in words: ‘I would like to photograph people in their homes for free (...) With no ulterior motives’. However, this impartiality professed by the author concealed a critical perspective towards the people, history and geography of his country.

The exhibition brings together some 150 works from several of his series to show the continuity of the artist's work. It also offers for the first time a dialogue with the work of other South African photographers between one and three generations after the author, such as Lebohang Kganye, Ruth Seopedi Motau and Jo Ractliffe.

Curated by Judy Ditner, Leslie M. Wilson and Matthew S. Witkovesky, the exhibition is co-organised by The Art Institute of Chicago and Yale University.

Both exhibitions are part of the official section of the PHotoESPAÑA Festival, and will be on view until the end of August.