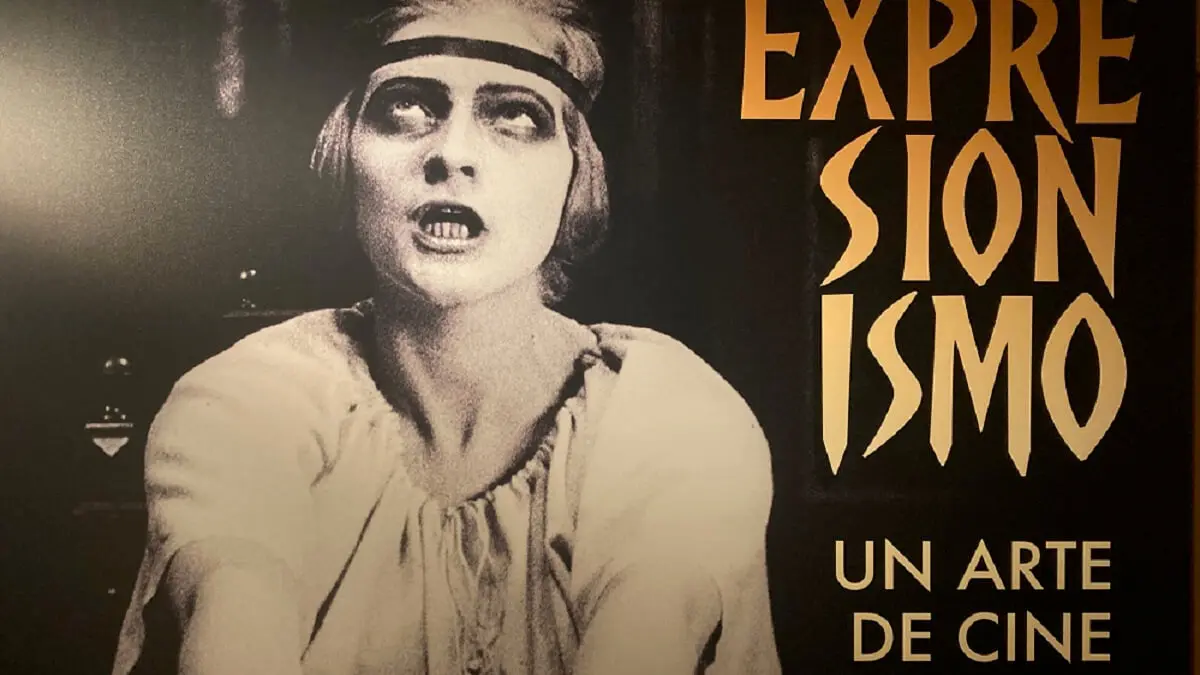

Expressionism, an art of cinema

With a carefully curated setting and curated by Maximilian Letze, director of the Institut für Kulturaustausch in Tübingen, the Canal Foundation is hosting the exhibition ‘Expressionism, an Art of Cinema’ at its headquarters in Madrid, which is already attracting record numbers of visitors eager for strong emotions.

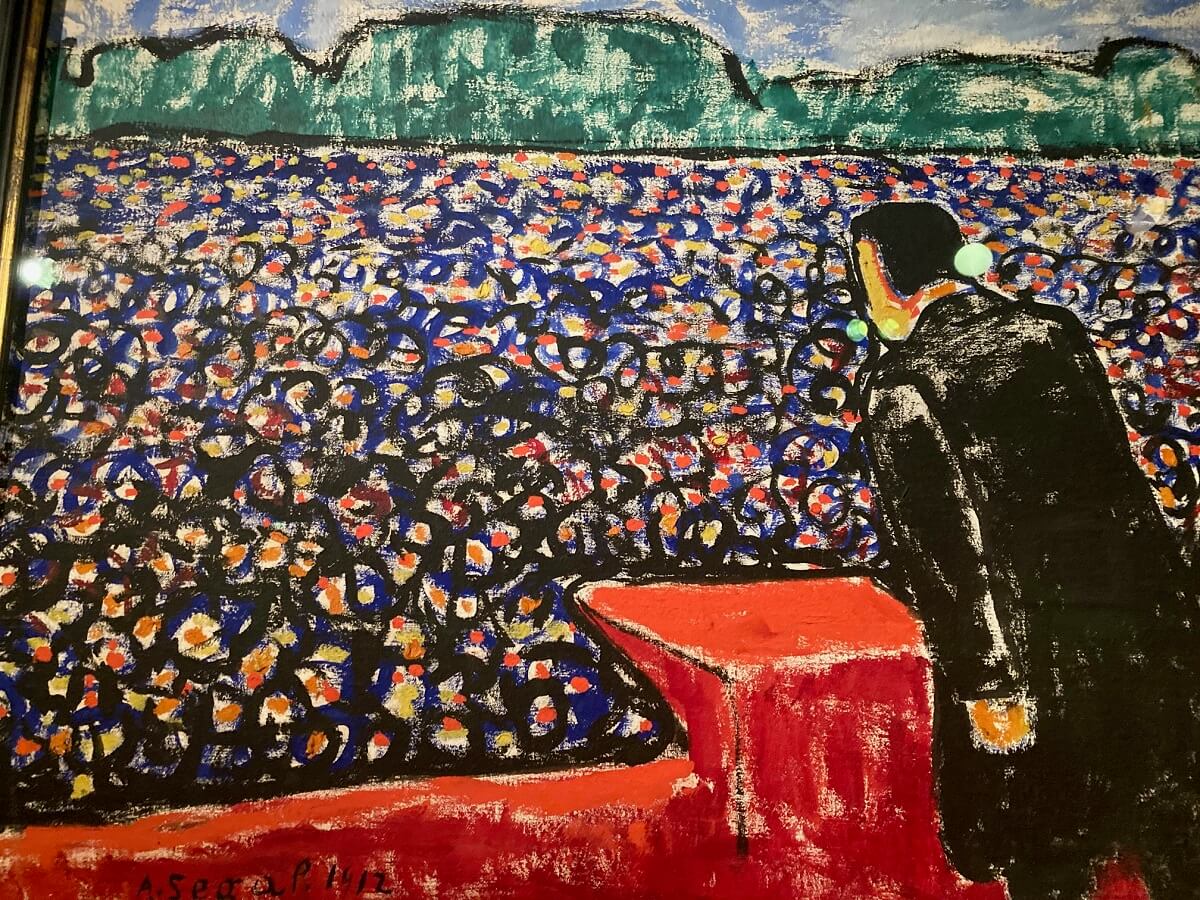

It was in the early decades of the 20th century that expressionism emerged in Germany as a revolutionary movement that transformed the visual arts, merging disciplines to create a unique aesthetic and emotional experience. In a context marked by the trauma of World War I, social tensions and industrialisation, the expressionist movement moved away from the objective representation of reality to focus on the expression of emotions and the inner world of its creators. To achieve this, artists used intense colours, distorted forms and twisted perspectives, elements that, afterlife their aesthetic function, manifested the collective feeling of existential unease that pervaded European society at the time.

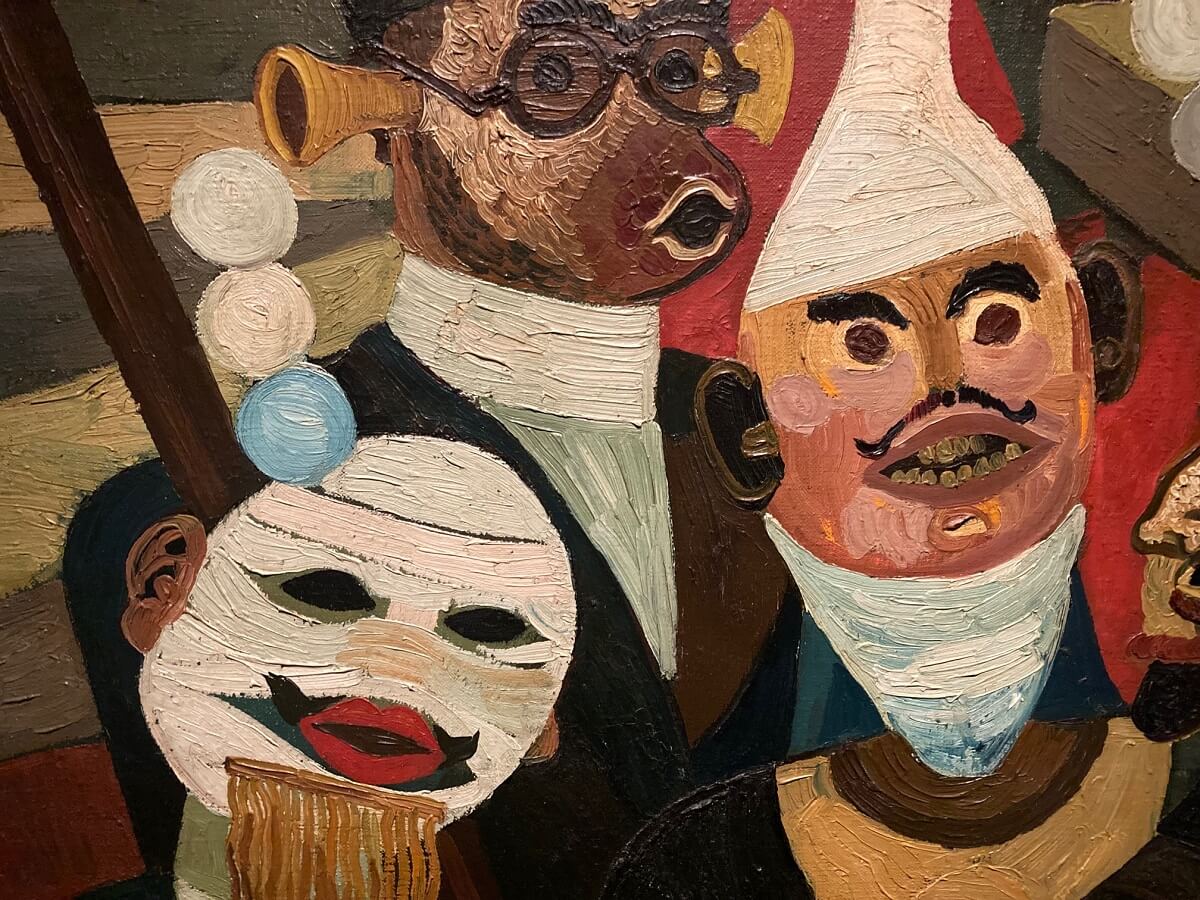

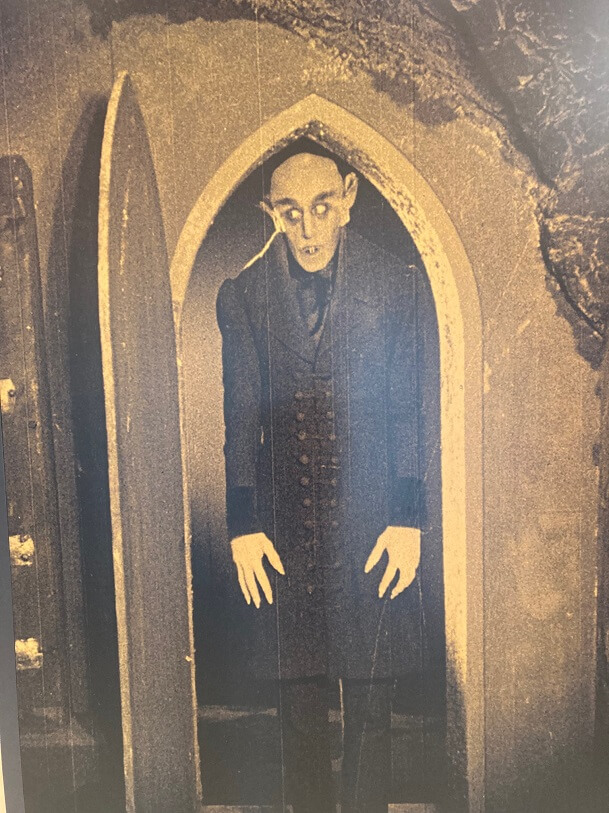

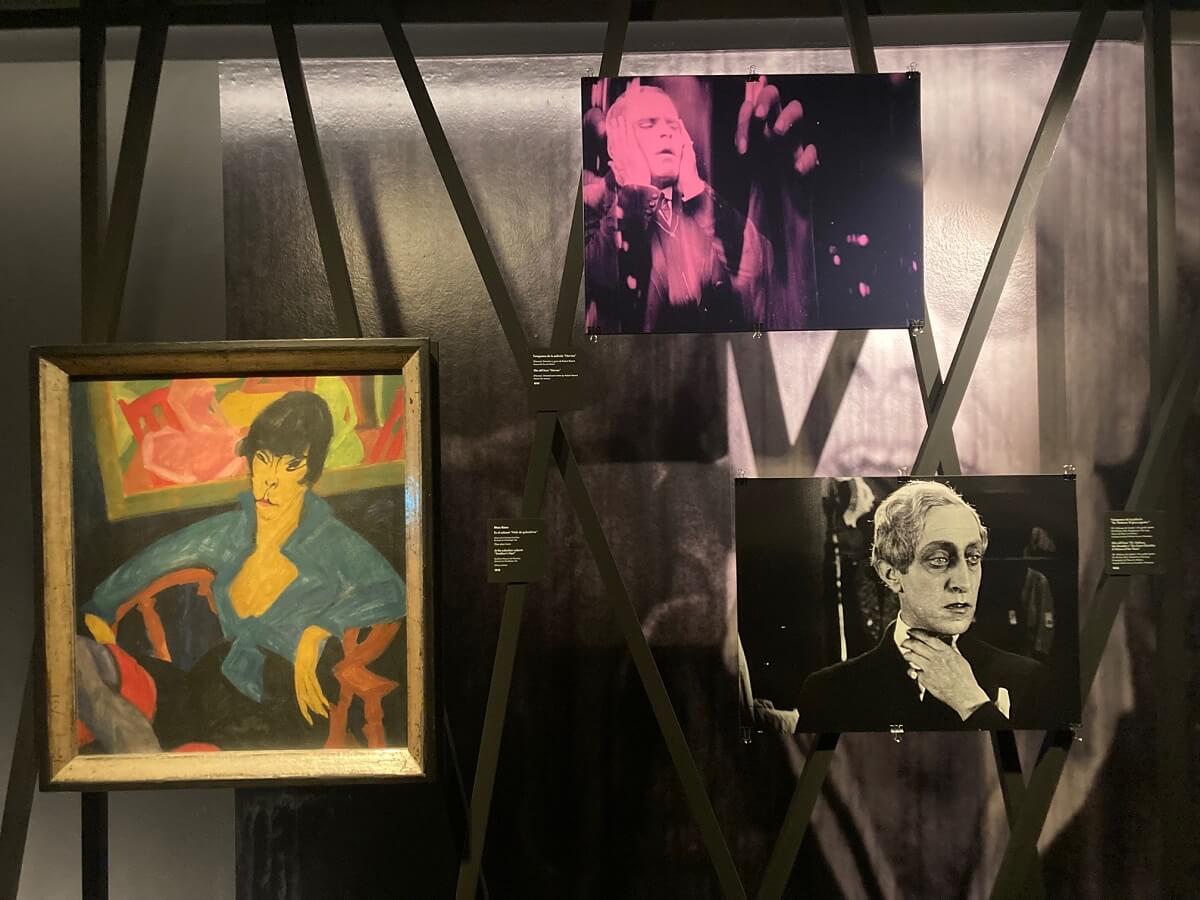

Within this movement, expressionist cinema found a new aesthetic framework, establishing an intimate dialogue with the visual arts and thus approaching the romantic ideal of the gesamkunstwerk or “total work of art”, a type that integrates all the arts. Iconic films of expressionist cinema such as “The Cabinet of Dr Caligari” (Robert Wiene, 1920), considered the manifesto of the genre; Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (F. W. Murnau, 1921) and Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927) stand out for their oblique sets, contrasting lighting and plots laden with symbolism. These works shared the aesthetic of artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, Franz Marc and Paula Modersohn-Becker, as well as the two main expressionist movements: ‘Die Brücke’ (The Bridge), founded in Dresden in 1905, and ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (The Blue Rider), which originated in Munich in 1911, whose expressive brushstrokes and distorted figures reflected themes of neurosis and social criticism.

The exhibition highlights the close relationship between expressionist cinema and art. Through a dialogue between a careful selection of paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures and the most representative films of the movement, it invites visitors to immerse themselves in an imaginary world that is both disturbing and fascinating, and explores themes such as the struggle between modernity and tradition and post-war trauma in interwar Europe. Although the rise of Nazism and the subsequent forced exile of many of its representatives marked the decline of German Expressionism, its legacy has left an indelible mark on contemporary art and artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and filmmakers such as Tim Burton and the recently deceased David Lynch, demonstrating how, in times of crisis, art and cinema reflected the human condition with an impact that still resonates today.

The creators of that era criticised the bourgeoisie, caricaturing it as superficial and hedonistic, while portraying the worker as a victim of mechanisation and new bourgeois values. For example, in Murnau's film The Last Man (1924), an elderly doorman at a luxurious Berlin hotel is demoted to toilet attendant due to his advanced age. In Metropolis, the workers live in an underground ghetto, operating machinery in oppressive conditions, while the bourgeois elite enjoy a life of luxury on the surface. Expressionism showed a fascination with the exotic and with spaces far removed from traditional high culture, such as the circus and fairs, which were seen as expressions of resistance and precariousness.

On the other hand, and in line with psychoanalytic theories, Expressionism maintained that the psyche exceeds the rational. The unconscious, dreams and repressed drives emerged in narratives that seemed to illustrate Sigmund Freud's theories. Thus, art turned towards the exploration of the unconscious, while cinema projected collective traumas and ghosts through nightmarish images.

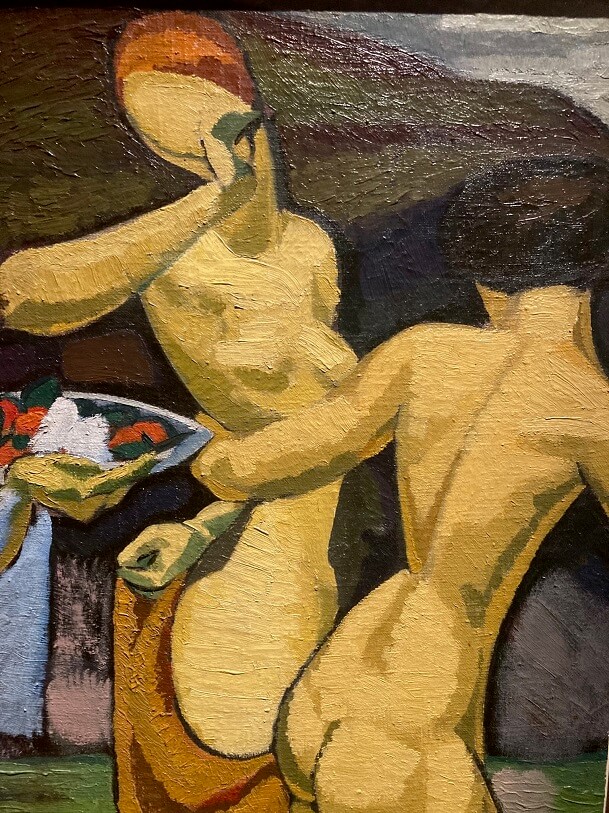

Women played a central role in this universe. In a Germany undergoing profound social transformations, with women gaining access to voting, education and the public sphere, Expressionism featured notable female painters such as Kollwitz and Modersohn-Becker, as well as the great screenwriter Thea von Harbou. Nevertheless, in artistic representation, women continued to appear as ambivalent figures: fragile and victimised, but also objects of desire or threat. Their iconography thus oscillated between ‘the fragile woman’, innocent and dominated, ‘the femme fatale’, independent and seductive, and ‘the grieving mother’, symbol of sacrifice and mourning.

In short, this is an exhibition that will certainly leave no visitor indifferent, and whose organisation and staging has been made possible thanks to the triple collaboration between the Canal Foundation, the Friedrich Murnau in Wiesbaden, and the Institut für Kulturaustausch in Tübingen.