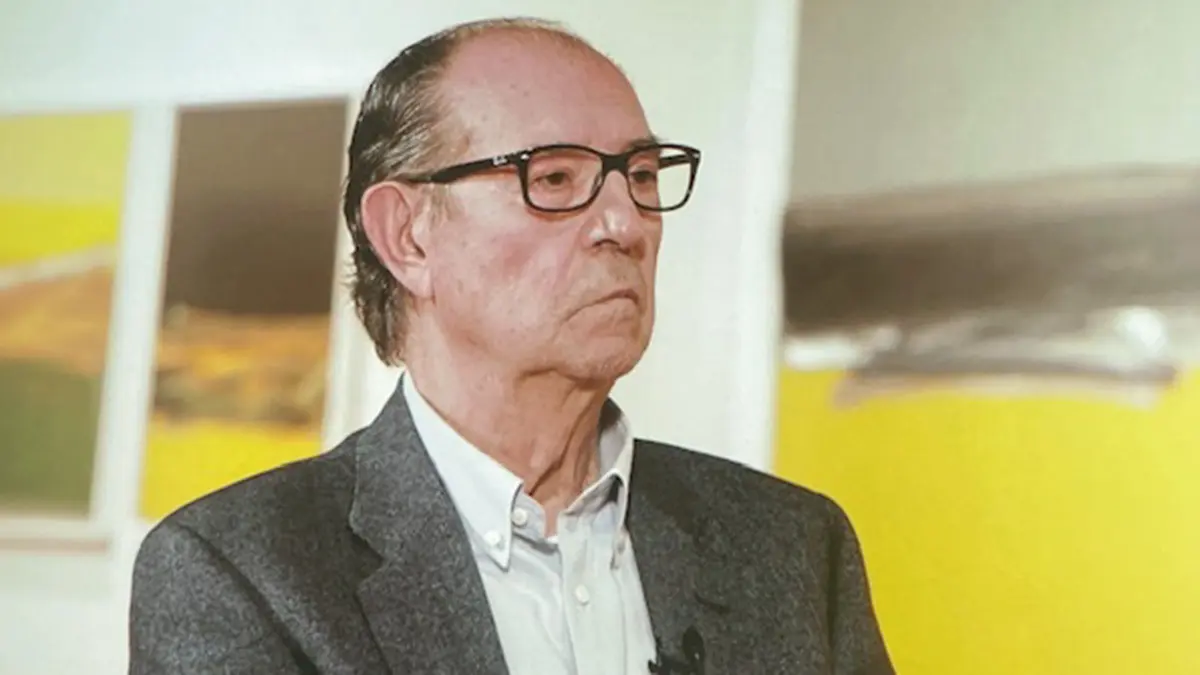

A monumental anthology of Rafael Canogar

At the age of 90, the Toledo-born painter Rafael Canogar (1935) is one of the most prolific artists: he has produced 5,000 works, far from Picasso's 20,000, of course, but almost as present as the genius from Malaga in the great museums and art galleries around the world.

We are dealing with an immense painter, as can be seen in the sixty or so works that make up the anthology that is on display in the CentroCentro space of the Palacio de Cibeles in Madrid, curated by Alfonso de la Torre. The exhibition includes mainly paintings, but also collages, sculptural reliefs as well as a free-standing sculpture, ‘Homage to those Fallen by Covid’.

Some of the works, divided into five sections that are not exactly chronological, come from the artist's personal collection, which is why they have rarely been seen in public before now. The exhibition traverses and summarises Canogar's work, giving a full account of his transition from early figuration to abstraction and his continuous closeness to, if not total immersion in, the artistic debates of his time, from 1949 to the present day.

The exhibition therefore refers to the work of an artist who always seems to be at an extraordinary moment in his creation. He is characterised by the evident intensity of his dedication to painting, ‘a fire that does not cease in the face of the abyss that the craft of creating entails’, in the words of his friend and great scholar of his work, Alfonso de la Torre.

Under the generic title of [I]Realidades, the five chapters into which the exhibition is divided constitute an ‘iconographic realm that reveals the fortune of those who have come to possess the joy of true knowledge’.

Nature, you have moved me; Circa 1957. Matter and sign: art other; Circa 1968. The secret royalty of pain; Abstractions and constructions: circa the eighties, and 1954-1955. Klee and Miró, magicians, make up this great universe compressed in the rooms of CentroCentro.

Both those closest in age to Canogar and the younger generations can contemplate the great commitment to society of this co-founder of the El Paso Group. He is now the only survivor of that legendary cast of great artists who, in the period 1957-1960, burst onto the scene with a bang to put Spanish artists back at the forefront of the art world. Luis Feito, Juana Francés, Manuel Millares, Antonio Saura, Pablo Serrano, Antonio Suárez, Martín Chirino, Manuel Viola, and the writers Manuel Conde and José Ayllón, together with Rafael Canogar, made up that unique group, all of them with the common denominator of commitment. That group opened up the channels of the avant-garde in our country, through expressiveness and chromatic austerity, with a peculiar treatment of light.

It was on this basis that Canogar reflected especially on the human condition and the effects of pain and time on it. If informalism was the common note, he returned to what he peculiarly called ‘realism’. His compositions, then, through relief and the fragment of the body or of fabrics, show fallen or wounded individuals, markedly alone or submerged in the mass, mourners, what Jean Genet called ‘the secret royalty of pain’. Works such as The Prisoner, in which he uses polyester, fibreglass and oil on board, when contemplated make discourses against violence unnecessary, because the violent, inhuman or dehumanised is inseparable from the materiality of the object.

If the exhibition opens with a view of the garden of the house of his first teacher, Vázquez Díaz, it closes with paintings that refer to the worlds of Klee and Miró, relevant both for American abstract expressionists and for European informalists. In both he found support for delving into expressionist abstraction.

‘I would like to have my feet on the ground, to be in touch with reality, to create organic, living forms, because art can no longer (today less than ever) be dehumanised... By finding (that reality) in its subjective and intimate truth’. He wrote this in 1959, and he has certainly fulfilled it amply.