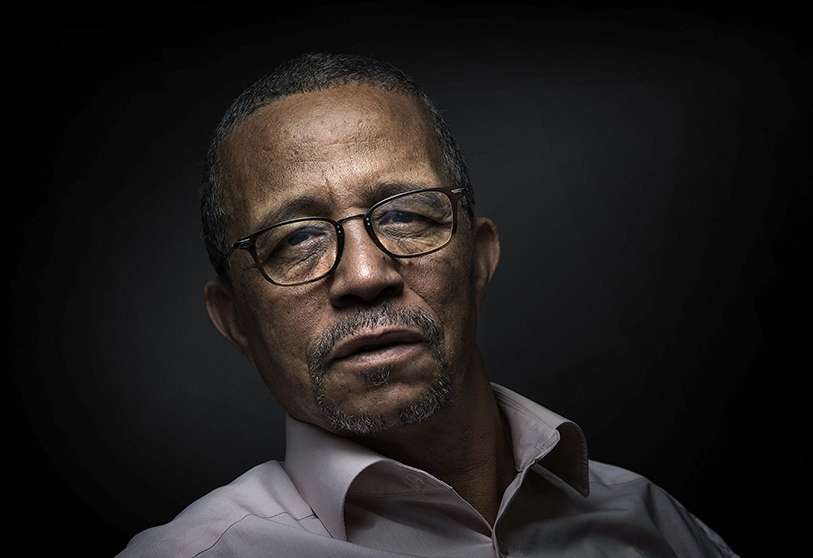

Yasmina Khadra: "Humanity has always disregarded values when interests and careers take precedence"

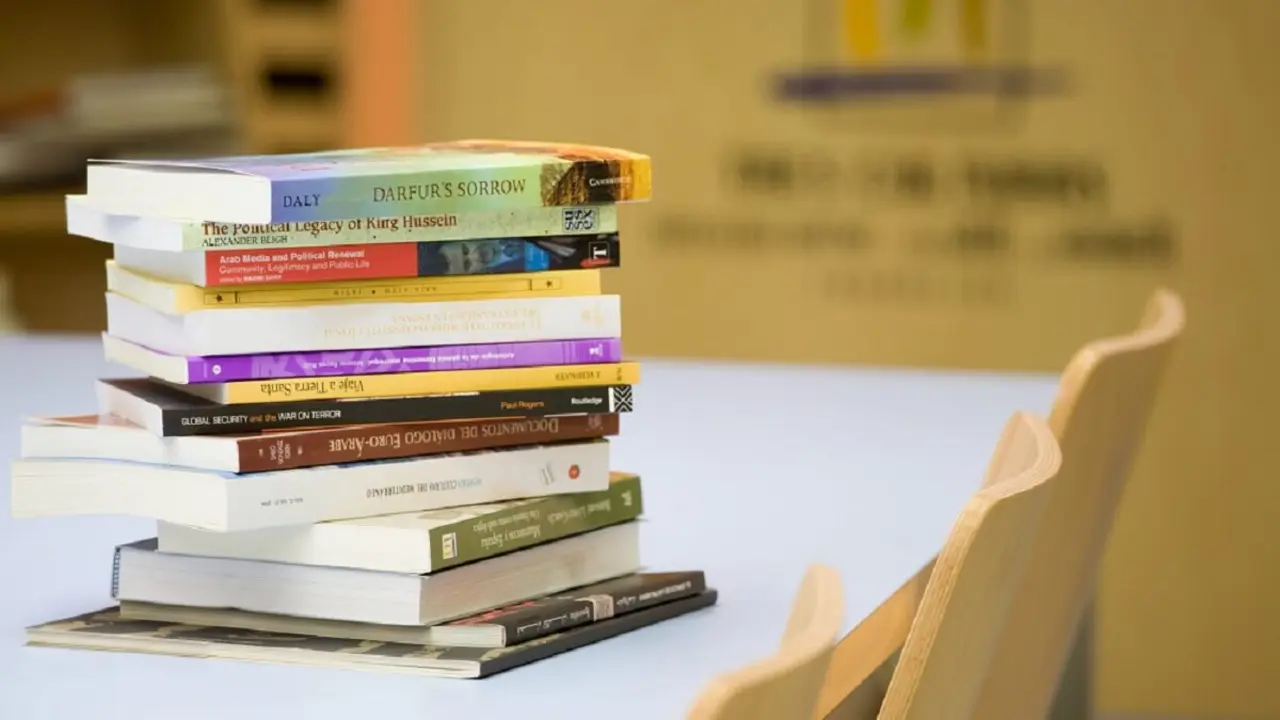

Yasmina Khadra is the pseudonym under which the Algerian author Mohamed Moulessehoul, with a very important literary career, writes. He talks to Atalayar about himself, the situation in Algeria and his work, which has already been translated into more than 53 languages and 58 countries.

THE WRITER

At what age did you start writing and under what name and why did you decide to start writing?

I was born to write. Since childhood I have been fascinated by the musicality of words. Besides, poets and writers have always been my best confidants. I try to be that for my readers, in turn, by sharing with them my hopes and dreams, and what I think I know.

The human factor in your novels is at the centre of the universe... loneliness, disillusionment, anger, but also love, reconstruction of the spirit and hope. What can you tell us about this? Have you encountered these situations in your country? Is there a kind of emotional misery in your work?

There is no emotional misery in my books, only a concern to popularise the human factor by opening it up to other cultures and mentalities. We live in a tormented age that distorts our judgement. Frustrations and unhappiness, uncertainties and ideological drifts, electoral promises and the disillusionment that accompanies them, all these unfortunate factors take us away from our share of humanity and place us in dangerous situations that sometimes degenerate. I try to shed some light on what we lack to better reconsider our prejudices and make it possible to wake up to the real issues instead of looking for scapegoats and scapegoats as we see in some countries where amalgamations and stigmatisation encourage the awakening of the foul beast that lies dormant in all of us. When I see fascism returning with a vengeance, and racism discovering its zeal, with all its shame, and outrageous radicalisation contaminating all militancy, I say to myself that we must react before misfortune strikes simultaneously in the four corners of the planet.

Did your experience as a soldier help you understand the human factor?

No doubt about it. Sharing your life with a multitude of people gives you access to each other's characters, anxieties, doubts, ambitions and defeats. For a writer, it is the best research centre, the most compelling and suitable breeding ground for inspiration.

What does your military experience mean in your life and work?

It is my whole life. It has enriched me emotionally, humanly and intellectually. And it allows me to stand my ground in the midst of storms. Without this experience, I would not have been able to stand behind the minefields I was forced to cross in order to advance. It forged my convictions and turned my setbacks into life lessons.

We have a lack of values in today's world, your books describe this very well. What can you tell us about this?

Humanity has always disregarded values when interests and careers take priority. We have given up what should make us feel better and help us to remain ourselves in a world where appearances attract all the limelight in front of the pyres. Nobody believes in themselves any more and everyone wants to be the product of others, even if they have to make a fool of themselves or sell their soul to the devil. Human values do not weigh much before stock market values. Money has become the absolute religion, the only prophet capable of bringing about miracles at any time and in any place. At one time, the Earth was spoken of as a village with Man at its centre. It was too good to be true. Man has no place in the race for profit. From now on, you are worth what you have. If you have two euros, you are worth two euros. You have an empire, you are an emperor. Talent, art, genius fade before any opportunist who has managed to make millions. You can be the bravest of the good, the Good Samaritan par excellence, the most charitable of the generous, the most gifted of the entertainers, if you're broke, you're not worth much. I don't know where greed will take mankind. One thing is certain, not where poets sing of life.

During the Algerian terrorist war (which is not exactly a civil war), where did your life go? If I am not mistaken, you were in the war for about 8 years... tell us about it.

There is nothing to tell. All wars, civil or classic, are monstrosities. The one that terrorised Algeria for more than fifteen years is no exception to the rule. It was the culmination of the rottenness of spirits, the breakdown of common sense and the implosion of frustration. When a nation does not pay attention to its mistakes, it ends up suffering. Algeria played with fire, and the fire almost destroyed it. No people is immune to excess. I spent eight years in the terrorist maquis wondering how the same people could harbour such fierce hatred against their own institutions and their own children. Even today, I do not have the answer. But there are many reasons for such tragedies, and there is one reason that wins the day: injustice! Because justice is the true foundation of social equilibrium, the only guarantee of the stability of a state. But there was no justice in Algeria, and what was supposed to protect it from itself collapsed when the anger of the humiliated broke all chains and deflowered all taboos.

When and where exactly did the pseudonym Yasmina Khadra appear, and is it a pseudonym that will remain so until posterity? What is the history of this pseudonym (I imagine you have already told it several times)?

My pseudonym is made up of my wife's two first names, a way of expressing my gratitude for what she has given me. She was born on 1 November 1994 in the Sid Ali cemetery (in the west of the country), where the 40th anniversary of the outbreak of the Algerian War of Independence was being celebrated. A homemade bomb, hidden in the grave of a martyr, exploded in the middle of the celebrations, killing five little scouts on the spot. I was there. And that was the day it all began.

Your work is very visual and poetic, I always see it surrounded by images, I imagine it every time I read it, I think that's very revealing of your writing style. If I were a film director, I would film 90% of his work. What I don't know is whether cinema would reach the depth of these works. How did it happen and what is your relationship with cinema and what kind of cinema?

Four of my novels have been adapted into films. Others are of interest to producers and directors. I have also written two screenplays that have nothing to do with my books. I love cinema. It is a wonderful invention and I would be happy to devote some of my time to it. Of course, adaptations, whether for film or theatre, are not necessarily faithful to the written work. Sometimes you are disappointed by the result. But you have to be reasonable. Directors are artists in their own right, their perception of the work they adapt is not always that of the writer. When you go from imagination to image on a screen, many filters are passed and that diminishes, distorts, overloads, impoverishes or enriches the original text. Personally, I respect directors for the interest they show in my novels and for the efforts they make to give them another dimension and another audience. I don't always agree with them and I'm not always satisfied with their work, but I don't try to interfere in their affairs or impose my vision of things on them.

You are a very popular and well-known writer (your works have been translated into 53 languages and 58 countries). What is your relationship with your translators, who are very good (at least the Spanish ones in our case)? Not to mention your publishers...

I don't know all my translators. I met some of them during my tours, but I didn't have enough time to get to know them. However, two of them have become my friends: Carlos, my Spanish translator, and Regina, my German translator. As for publishers, I have excellent relations with Alianza (Spain), Sollerio (Italy), Larousse (Mexico), Sonia (Poland). The others, apart from my French publishers, I meet them sporadically at festivals or international fairs and lose sight of them immediately afterwards.

A writer writes books and it is the reader who makes the writers, what do you think?

These are my own words. I would add: without readers, the writer is a dead letter.

Are your books also produced in Arabic? How is reading in the Arab world, and does the Arab press recognise you as a renowned writer?

I am known in the Middle East, but not widely read. However, a minority is discovering me. When I go to Dubai or Qatar, readers, especially women readers, come to listen to me. Things are starting to improve.

Algerian literature (in French) is becoming increasingly richer, especially since the works of Moulud Mammeri, Mouloud Feraoun, Mohammed Dib, and others, for example, have recently become known? What is the reason for this boom?

Talent. Algerians have a lot of talent, but little visibility. This is a loss for world literature, and it's a pity.

Your books have many settings, situations, places, villages, towns, cities, etc. Have you set foot on Algerian soil? Have you set foot on the soil in each of them for your work?

Flaubert said that everything we invent is true. I have not been to all the countries I describe in my books (except Mexico, Lebanon, the Maghreb and Cuba), but my readers find that I am quite accurate in my descriptions. I ask residents, I consult documentaries, I try to understand a country in terms of the mentality and culture of its people. This puts me in a situation. The rest I get from my intuition.

LITERARY WORK

Let's talk about some of your novels. Your first book is "Amen" in 1984. How did it happen...?

Very badly. It was my first publishing experience and I was cheated by a not very honest publisher. I self-published it and the novel never saw the shelves of bookshops.

"What are the monkeys waiting for in 2014"...An extraordinary crime and political novel. Worthy of the best Hammett, Chandler, James Ellroy, etc. A crime novel, but also a political novel about Algeria at the end. Is Algeria fed up with its leaders? Tell us about this book.

This novel is a radiography of a state taken hostage by the leaders of the mafia, most of whom are now in prison. It tells the story of their control over the country's wealth, the enslavement of an entire people, the institutionalisation of corruption, the law, influence peddling, the promotion of mediocrity, the rotting of mentalities and the perversion of justice. Some Algerians consider it their favourite novel because it is so blatantly true.

"Les Vertueux", 2022: the suffering of an (Algerian) person in the first half of the 21st century. A wandering person who suffers and desperately searches for answers... How does this period relate to Algeria today? A mention also of your birthplace KENADSA in the book (page 338) What influence does your birthplace have on your work and in particular on this book?

I prefer to let the reader discover this novel for himself. It is my most beautiful novel, the most precious too, because it is crossed, from beginning to end, by the memory of my mother, who died while I was writing it. I have put everything I know how to do into this book, which recounts a tormented period in Algeria, more specifically the first half of the 20th century, which shaped the Algerians of today. It is a formidable odyssey that begins with the war of 1914-1918 and extends into the 1950s. I can say no more. This novel is full of twists and turns, served by a sustained pace. It would be sad to spoil its intensity.

What is your relation with the world of comics, the cases of "The Attack" and "The Swallows of Kabul"?

It isexcellent. A very nice adventure and a magnificent initiative that can broaden the audience of a work even more. Just like the film and theatre adaptations.

The book "The Swallows of Kabul" was inspired by Afghanistan during the first reign of the Taliban. Years later, the Islamist movement returned to power in the country. So the repression suffered by the characters in the play, especially the women, is the same repression suffered by the citizens of Afghanistan today. What parallels do you draw between the first Taliban government - narrated in "The Swallows of Kabul" - and the present one? How do you think the international community should act against the Taliban?

They are the same caliphs of the Apocalypse. They have come back to finish the job of undermining that the previous Taliban did not have time to finish. It is really depressing. Twenty years of investment, of daily struggle, of hope and emancipation to come back to square one. When I think of the young girls who thought they were growing up in the open air and who are now forced to wear the burqa to mourn their happiness, who are forbidden to go to school, to work, to dream, I am on the verge of abjuring. But the struggle continues. No misfortune lasts forever. One day the Taliban must realise that they have not come to save a nation from sin and depravity, but that they are the sin and depravity. They will soon see that when one has no edifying plan for society, and opts for tyrannical repression, they will only erect their own scaffolds.