Europe faces itself

Europe is at a turning point in its history. This is nothing new, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine brought about a change in the - erroneous - perception that a new war in the Old Continent was impossible. Years of disarmament, far removed from the seemingly forgotten idea of a Europe of Defence, have left Europeans several steps behind a reality that has ended up running over them.

A reality check

Sunday's elections have shown that a large part of European society is moving away from the spirit that gave rise to the EU more than three decades ago. Populism has grown, as many polls predicted. It is the natural consequence of the moment the continent is going through, threatened by the growth of violence around the continent.

The war in Ukraine is escalating, while the Hamas terrorist attack on 7 October triggered an escalation of violence in the Middle East that has led countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom to take an active role against the Houthi militias in Yemen. The climate of tension at the international level has led to a moment in which society is fearful of experiencing first-hand the clashes it sees around it.

The causes of this drift are many, but the perspective should not be lost. Europeanism remains in the majority, despite the growth of Eurosceptics. And the intention is to isolate all these formations, as Ursula Von der Leyen said shortly after the results were known. The centre-right will seek the support of the Social Democrats to avoid a pact with the far right, which could lead to even greater polarisation on the Old Continent.

The rise of populism as a consequence

The gap between the left - along with the centre and centre-right, as they now want to form in Europe - and the more conservative right has widened. Polarisation, attacks and disqualifications between formations are increasing. And this has been reflected in society, which is opting for more extremist formations, especially in the right-wing spectrum.

This is evident in such notorious rises as that of Marine Le Pen's ultra-right-wing party which, with its uncontested victory, has forced Emmanuel Macron to bring forward the legislative elections in France. But it is not the only one of concern in Europe. The far right has also won elections in Italy, Austria and, as usual, Hungary. But its rise has had an important weight in key countries in European politics, such as Germany, where the far-right Alternative for Germany has been the second most voted force, ahead of the Social Democrats of the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz.

In Spain, the growth of the extreme right is also a reality, although much more moderate than in France or Italy, where they are already the most voted parties. Vox has won six MEPs - two more than in 2019 - at the same time that the new ultra force, Se Acabó la Fiesta, led by Alvise Pérez, has burst into the European Parliament with three seats. Between them, the two formations account for almost 15% of the votes in Spain.

Although predictable, this rise of populist parties can be explained both by the tension in Europe and by the threats and fear that have flooded the Old Continent. Insecurity has grown at an alarming rate, due in large part to years of inaction in the face of the rearmament of countries bordering the European Union. And although belatedly, Europe is already putting on the table increased spending in the military portfolio and the revival of military service in more and more countries.

Bringing back compulsory military training

In some cases it never went away or, at the very least, it was revived only a few years ago. This is the case in a growing number of European countries. Greece, Austria, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Cyprus, Denmark and Sweden already have it. Latvia was the last of these, forcing 18-27 year olds to enlist for 11 months of compulsory military service.

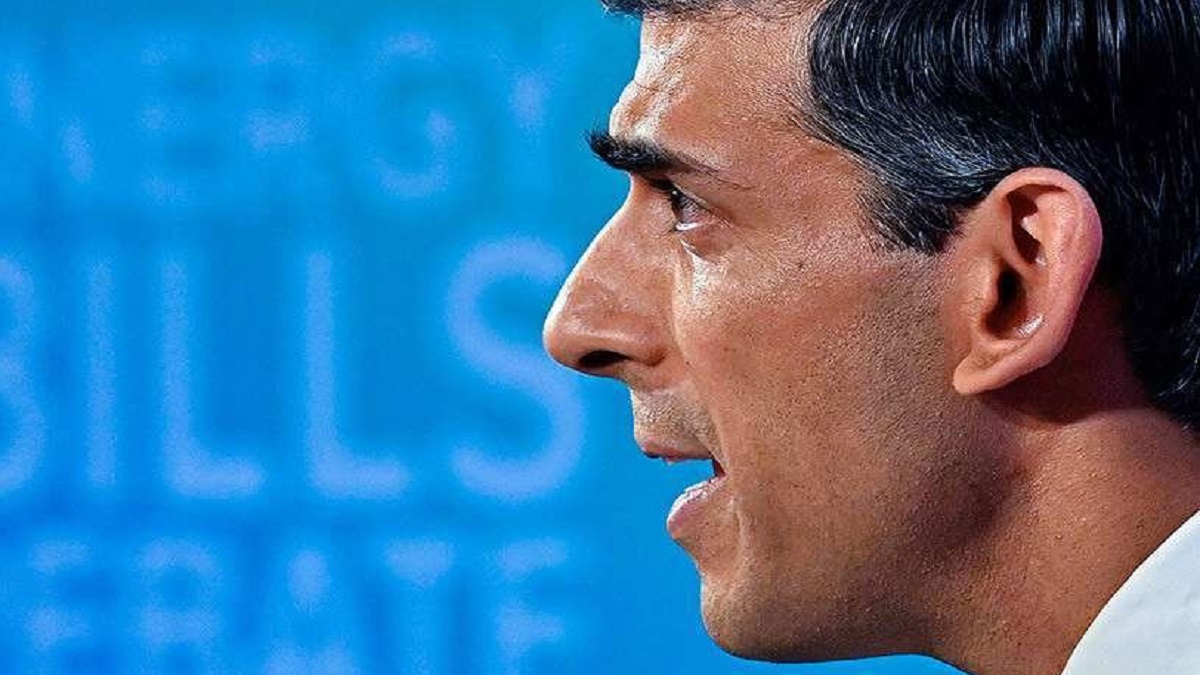

But there is every reason to believe that this list could grow significantly in the coming years. Rishi Sunak, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom - albeit with an almost certain defeat in the 4 July elections - has already put the idea of bringing back military service on the table. This is similar to the idea already being contemplated in Germany and France, which are fearful of the rise of warmongering both within and beyond Europe's borders.

Europe knows that war on its territory is a possibility. People should not be frightened, but neither should they deny what is happening on the continent's doorstep. The Europe of Defence, forgotten in the naïve belief that peace would live forever, can be rescued from the warlike drift of the international chessboard. And the sooner we work to prevent this, the fewer wounds we will have to heal.