Peace with the PKK in Turkey could be getting closer

The Turkish government has announced that the disarmament process of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) could begin in a matter of days, representing a significant step forward in the search for a solution to a conflict that has lasted more than 40 years.

This conflict has deeply marked Turkish domestic politics and its role in the Middle East. If the current dialogue succeeds, Turkey and the Kurdish communities could set a precedent for resolving identity-based armed conflicts, as Colombia, Ireland, Spain and Sri Lanka have done. Rather than simply defusing an insurgency, this would be about transforming a structural challenge into an opportunity for reconciliation and lasting peace.

Context

Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) proposed a reconfiguration of the map of the Middle East under the control of the European powers, including the possibility of a Kurdish state. However, the victory of Turkish nationalist forces led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in the War of Independence (1919-1923) prevented its implementation. The subsequent Treaty of Lausanne (1923) defined the borders of the new Republic of Turkey and ruled out any autonomous Kurdish entity. From then on, national policy focused on building a modern, unitary and secular state, inspired by Kemalist ideology, which promoted a national identity based on the Turkish language and culture, reducing the space for different expressions of identity such as the Kurdish one.

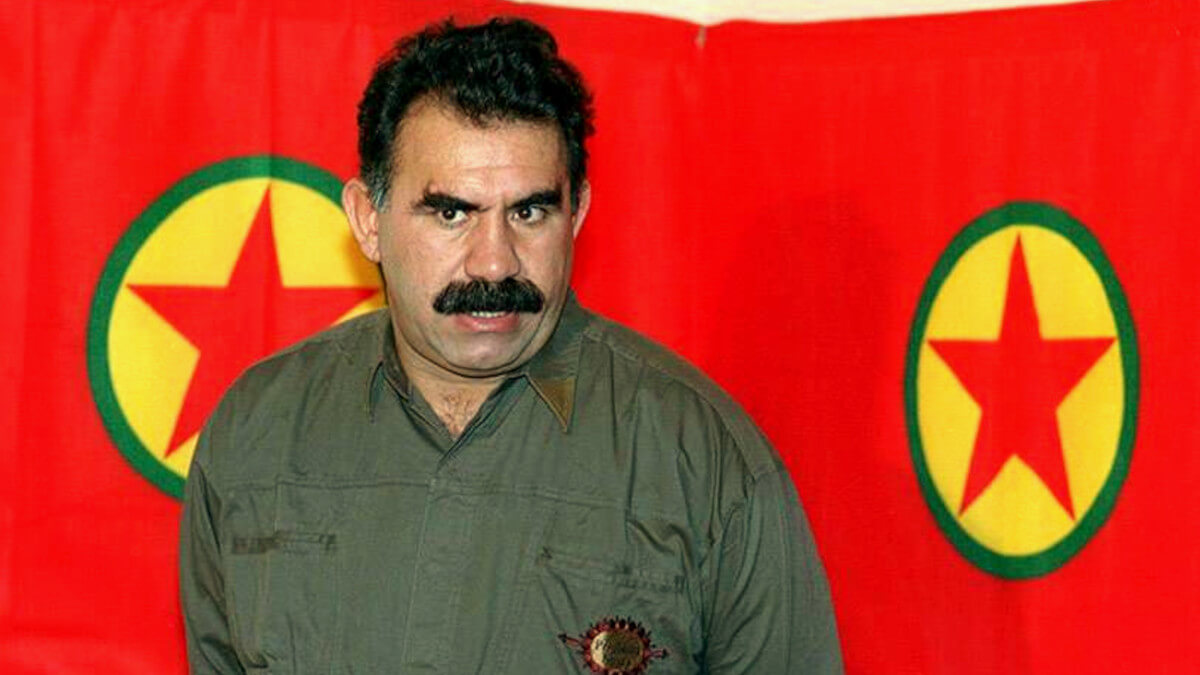

The Kurdish conflict intensified in the 1980s with the emergence of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), founded by Abdullah Öcalan in 1978 with a Marxist-Leninist ideology. In 1984, the group launched an armed insurgency with the initial aim of creating an independent Kurdish state, although it later reformulated its demands towards greater autonomy and recognition of cultural rights. Classified as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the European Union and the United States, the PKK has been at the centre of a conflict that has left more than 40,000 dead.

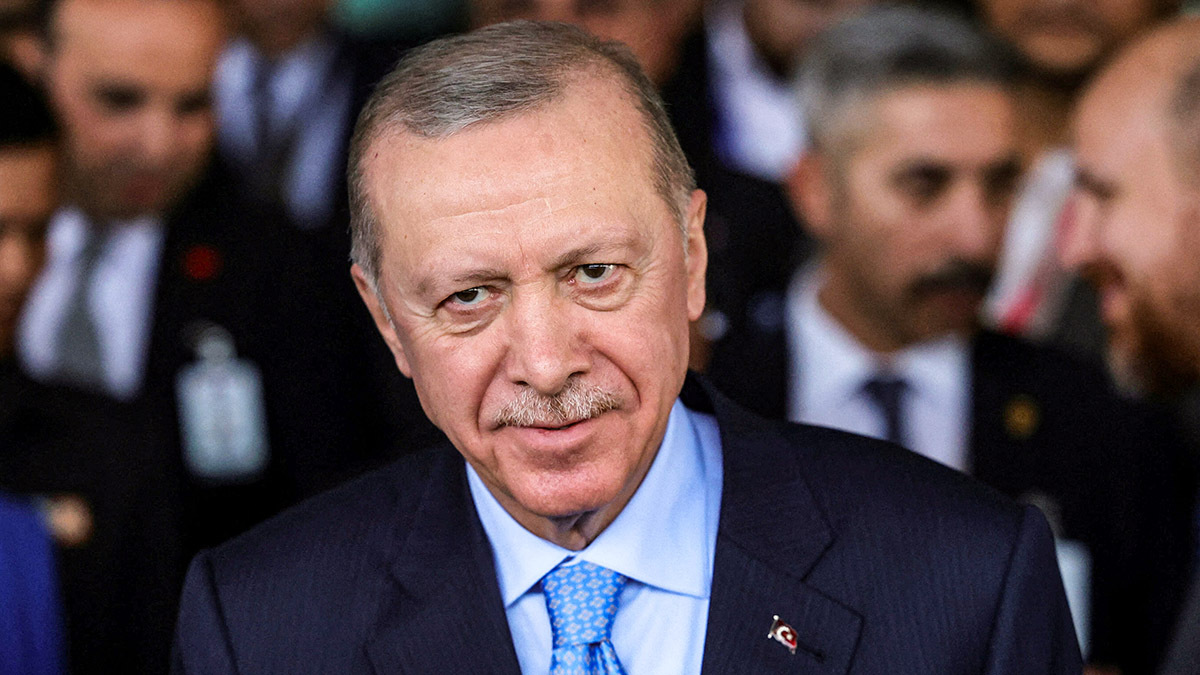

In the following decades, the Turkish state's approach oscillated between repression and attempts at dialogue, as was the case during the 1990s with the reforms of Turgut Özal and, later, during the first terms of the AKP. However, the hardening of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's government, especially after the attempted coup in 2016, consolidated an authoritarian line that securitises the Kurdish question and has weakened the avenues for political resolution.

However, recent signs point to a possible change in the dynamics, with concrete steps towards de-escalation and disarmament of the PKK, opening a hopeful window for reconciliation.

Are we getting closer to peace?

The Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) could begin handing over its weapons in a matter of days, according to the spokesman for Turkey's ruling party, Ömer Çelik, who described the coming days as ‘extremely important for a Turkey free of terrorism’.

This signal represents the clearest progress so far in the group's disarmament process, which in May decided to disband and end more than four decades of armed conflict with the Turkish state.

PKK sources in northern Iraq confirmed that a small group of fighters will hand over weapons at a ceremony in Sulaimaniya, under the supervision of the Iraqi central government. This act, considered a gesture of goodwill, seeks to build trust so that Turkey can move towards a lasting peace.

At the same time, Turkish intelligence chief Ibrahim Kalin visited Erbil to coordinate with Iraqi Kurdish leaders on measures against terrorism, in a context where the disarmament of the PKK could boost political and economic stability not only in Turkey but also in the Kurdish regions of Iraq and Syria.

A lasting peace would have large-scale implications

National

Over time, this conflict has contributed to the concentration of power in the central government and the weakening of local autonomy, especially in the Kurdish-majority provinces. It has also been used as a pretext to restrict fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, political participation and the use of the Kurdish language in the public sphere. The narrative of 'Kurdish separatism' and the violence associated with the PKK have facilitated the social acceptance of authoritarian policies under the logic of national security. A peaceful resolution of the Kurdish question would not only reverse this process, but also open the door to a more democratic and inclusive redesign of the Turkish state.

Regional

This conflict has deeply affected Turkey's relations with its neighbours—Iraq, Syria and Iran. From the Turkish state's point of view, Kurdish aspirations have been seen as a transnational threat. Therefore, instead of being seen as an opportunity for cooperation, Kurdish communities on both sides of the border have been treated as obstacles. Overcoming this logic would open up new possibilities for alliance in the region. An agreement with the Syrian Kurds, for example, similar to the one already in place with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Iraq, could mark the beginning of strategic cooperation. Instead of viewing the Kurds as rivals, Ankara could begin to treat them as key partners in its outreach to the Arab world.

A rapprochement with Kurdish communities would also shift the regional balance. Turkey and Iran, which have maintained an ambiguous relationship on this issue—cooperating at times, competing at others—support different Kurdish actors: Tehran has moved closer to more left-wing groups such as the PKK and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), while Ankara has backed conservative figures such as the KDP. As long as the conflict with the PKK remains active, this division benefits Iran. If the PKK dissolves, Turkey could gain influence.

International

The Kurdish question has also strained Turkey's foreign relations, particularly with the United States. US support for the YPG (the Syrian arm of the PKK) triggered a serious bilateral crisis. In response, Ankara sought alliances with Russia and Iran in the Syrian conflict, which led to the Astana Platform (2016). But this cooperation with Moscow is not stable. If the conflict with the PKK is resolved, Turkey could reduce its dependence on Russia and move closer to the West again.

Thus, peace with the PKK would eliminate one of the main sources of conflict in foreign policy, improve relations with Washington, strengthen Turkey's position in NATO and open a new chapter with the European Union. But for this shift to be real, a ceasefire is not enough: institutional change is needed to recognise identity diversity, protect linguistic and cultural rights, and guarantee the political participation of Kurds.

The moment is delicate but promising. There is social and political support for moving towards peace. The challenge is to turn that consensus into concrete reforms. If it succeeds, Turkey will not only heal a decades-old internal wound: it will also redefine its place in the region and the world.