The next leader in Iran

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

Rumours related to the delicate health of Iranian leader Ali Khamenei have resurfaced during the 2023 summer. The succession issue could come at a very sensitive time for Iran, given its serious internal problems. This is intensified with Iran's important position in its regional sphere and the significance of its actions in the changing international system. The election of a new leader will bring with it a fierce struggle between the various Iranian power groups, who will seek the victory of the candidate that suits them best. Given the time passed, the new leader could belong to a generation that did not participate in the Islamic revolution or in the patriotic war against Iraq. Whatever the outcome, the situation will be one of increased uncertainty and destabilisation.

Introduction

The age and health of Iranian leader Ali Khamenei are issues of concern due to the domestic and external situation of his country, and the path that Iran’s next leader will take.

The leader's ailments date back to 2014, when he underwent surgery for possible prostate cancer. He was also seriously ill in September 2022, having to cancel several public events and undergo surgery due to an intestinal obstruction1. Rumours about his health circulated again in summer 2023, but his chief of staff had a strange way of playing it down, stating that "every now and then it is said that the leader is sick"2.

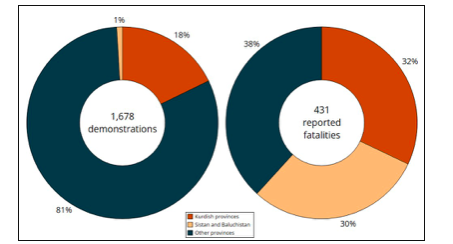

With its highest authority in poor —if not precarious— health, the Iranian regime has had to face internal destabilisation with strong repercussions on social media around the world. September and October 2022 saw a series of violent protests following the death of Kurdish-born activist Mahsa Amini, who was held in police custody, resulting in more than 200 people killed and thousands arrested3.

The existence of social movements in Iran throughout its history and repression by authorities is nothing new. Popular outbreaks have traditionally had a vindictive character, usually seeking some kind of economic concession or the modification of certain regulations. In this way, the groups concerned sought the recognition of some kind of right by demonstrating4.

However, the latest protests marked a turning point because they sought regime change based on the concession of political and human rights demands. Moreover, despite the fact that Mahsa Amini was a woman, Kurdish and Sunni, the protests united most social groups against discrimination based on gender, origin or religion. Likewise, protests were transversal across all social classes, unifying the urban middle classes and workers in the main cities and extending both within the country and in the diaspora. This also took place against a backdrop of social media activity, which led to the suspension of internet services5.

Despite all this, it seems that the Ayatollahs' government has been able to resolve this crisis, as neither the bazaari system traders nor the oil workers have joined the protests, which faded away over the course of 20236. It also seems that external threats are a cohesive factor for the Iranian people, who feel at odds with Israel and the US. At the same time, Iran maintains common ground with its Russian ally of convenience over the Ukraine conflict and relations with the Saudis have improved exponentially under the auspices of China7.

Meanwhile, the different power factions of the politico-clerical elite await the change in leadership. One possible orientation of the positioning of these elites could have been the outcome of the last presidential election, which was won by the ultra-conservative Ebrahim Raisi, a ruthless prosecutor during the purge of the Islamic revolution and political prisoners in the late 1980s8.

It should be taken into consideration that presidential candidates are selected or discarded by the Guardian Council of the Revolution, so only seven candidates could run. Only Abdolnaser Hemmati, president of the Central Bank, was selected among all the moderates, with little chance of success. Moderates rejected include Mostafa Tajzadeh, a former interior minister who had been imprisoned for protesting against the regime, and Ali Larijani, a prominent former speaker of parliament. More radical fundamentalists, such as former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, were also ruled out9.

Selecting a leader in the context of power factions

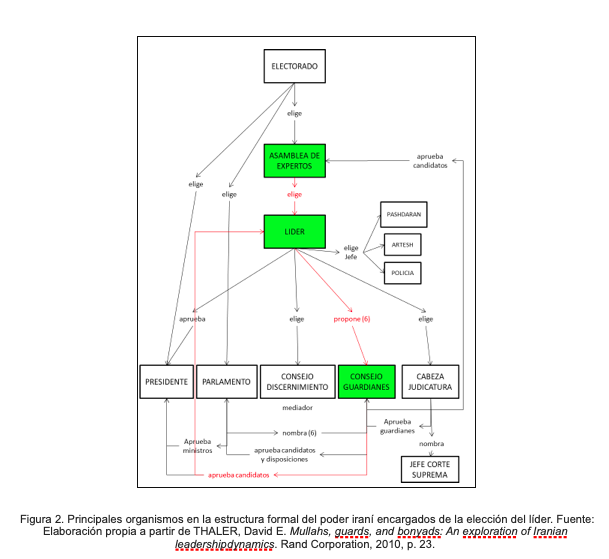

Iranian state institutions ensure their survival through a sophisticated and redundant system of power balances and checks between the various bodies that make up the regime. The position of the leader in this framework is very important because as it is vested with great powers. As such, he not only directs state action from a religious and political point of view, but can also authorise or reject the appointment of leading figures in public life, creating a structure of dominance in tune with his own person.

This complex web is reflected in the Constitution, where the religious nature permeates the entire text. The existence of a leader is justified in Article 5, as this figure occupies the position of the Wali al-Asr10 during his occultation. The leader's powers are very broad and are reflected in Article 110, where he is granted power to design broad outlines of policy in general and the supervision of activity during its development. The leader also has command of the armed forces and the power to accept or dismiss the main state authorities. Article 57 of the constitution states that the branches of government are independent of each other and consist of ‘the legislature, the judiciary, and the executive powers’. However, they must all carry out their functions under the supervision of the supreme leader11.

According to Article 107, the Assembly of Experts is the body responsible for appointing or replacing the leader in the event of death or lack of capacity or suitability. This 88- member assembly is elected every eight years based on a quota proportional to the number of residents in each of the provinces. Furthermore, the leader retains the power to appoint, reject and dismiss Assembly members. Effective control over the leader's decisions could be glimpsed since, according to Article 110, the Guardian Council can veto candidates. However, the leader's power over the Guardian Council is significant, as he directly appoints 6 of its 12 members from among prominent jurists. The other six are appointed by the Parliament or Majlis12. Thus, concentrating power in the leader is seen to give him great capacity to control the Assembly and the Council during his term of office and to leave the members most sympathetic to his tendencies on his death.

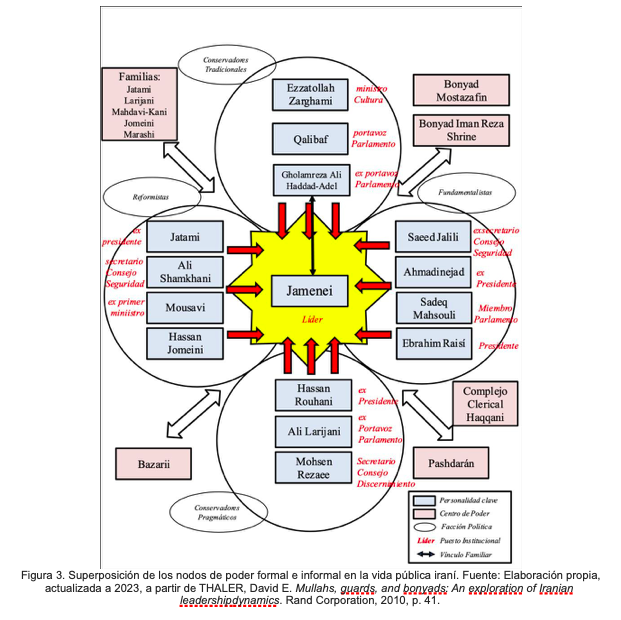

Despite the formal mechanisms in place for leadership succession in Iran, a number of informal relationships overlay the official structure.These consist of religious, cultural and economic power groups, as well as the armed wing of the revolution formed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard or Pasdaran. The elite Quds Force, commanded by General Esmail Qaani, plays a very active role in this organisation13. In addition to all of the above, affinity and family ties place their individuals at the centre of the power structure.

It should also be borne in mind that many former leaders of these influential groups belonged to an earlier generation and that a significant proportion are now deceased or have retired from public life. As a result, the landscape of formal and informal power structures has been renewed with new members who, while maintaining an ideological current, bring new ideas into Iranian politics.

The arrival of Khamenei marked a second stage, as his religious authority was not up to the standards of the previous marjas and he had to make changes in the structure to consolidate his power. For this reason, during this period the role of the foundations was strengthened, gradually placing related people in key positions, who, due to family ties or gratitude, positioned themselves in favour of the faction that had given them their privileged position. A veritable network of clientelism and a heterogeneous and adaptive web of relationships was formed at the end of this stage, in which the different factions fought to place their acolytes in order to extend their power. For their part, individuals were adapting to the situation according to their own interests and it was not uncommon to see certain changes of attitude so as not to be displaced from their positions.

The third stage was the integration of the previous religious, economic and political powers with the elements of military power linked to the revolutionary elites. It is therefore understandable that Pasdaran figures such as Ahmadinejad, Qalibaf and Shamkhani have appeared in public life. This military organisation, but linked to the other elements of power and with its own internal dissent, aspires to high power quotas and is often favoured by the more conservative tendencies.

It is feasible that the generational handover could lead to a fourth stage, with new individuals occupying key positions who have not experienced the Islamic revolution first- hand. Regardless of their bias and affiliation, these new elements are likely to impose new ideas within their currents of thought, giving way to a possible evolution of the Iranian regime.

Throughout this succession of stages there has only once been a change in leadership, following the death of Khomeini and the appointment of Khamenei as the new leader. As discussed in the preceding paragraphs, the process leading up to his appointment was tortuous and somewhat unpredictable.

Grand Ayatollah Montazeri had been appointed as Khomeini's successor in 1985, but in 1989 he fell out of favour with the leader for criticising the loss of social rights and freedoms caused by the government's stance and the executions of prisoners. The leader’s change in attitude could have been the result of a smear campaign by reformists, who thus removed Montazeri from the path to leadership. This campaign may have been orchestrated by then parliamentary speaker Rafsanjani, together with Prime Minister Mousavi, who had previously supported Montazeri's thesis but had distanced themselves from him because of their opposition to the arms deals with the US, in what became known as Iran-Contra14.

After Montazeri's dismissal, Khamenei was appointed by Khomeini to lead Friday public prayer in Tehran. Following his death that same year, a closed meeting of the Assembly of Experts was held with each power group seeking to position its aspirant. Externally, however, the Assembly declared that it had several candidates. The fact is that the main marjas, such as Golpayegani, were eliminated and the names of those backed by the most influential groups emerged, most notably Rafsanjani and Khamenei. A possible consensus solution by forming a collegiate leadership between then president Ali Khamenei, the chairman of the Assembly of Experts, Ayatollah Ali Meshkini, and the head of the judiciary, Abdul-Karim Mousavi Ardebili, was even discussed for some days. When the short-list was set, Rafsanjani, as parliamentary speaker, opted for Khamenei, possibly hoping for a reward in return15.

The assembly eventually elected Khamenei, who did not hold the highest rank in the clerical ladder, and the constitution was amended accordingly so that this would not be a stumbling block. He was then elevated to the rank of ayatollah and the figure of the prime minister was abolished in the Constitution, sacrificing Mousavi in order to promote Rafsanjani as the future president16.

As can be seen from the facts, the factionalism of the groups combined with the personal interests of individuals produced a relatively unexpected result. This was a reversal of a situation that should have seen a reputable religious figure, with a high position in the clerical hierarchy and with significant support from the reformists appointed as Khomeini's successor. However, the more radical conservatives, starting from a position of weakness, eventually managed to unite other interests that led to Khamenei's leadership. That a situation similar to what was once described as ‘spontaneous divine intervention’ could occur again after the death of the latter, leading to a similar fate, should not be ruled out17.

The process of appointing the future leader

The plot for electing the next leader will be controversial to say the least. As seen in the previous section, many of those responsible for this selection belong to power groups and will be strongly influenced by them.

Iran’s history is dotted with many examples of bitter factional fighting. One of the most significant was in 2011 when President Ahmadinejad dismissed Oil Minister, Masud Mirkazemi, before a meeting of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)18. This infighting among hardline conservatives ended with the leader withdrawing his support for Ahmadinejad, who was accumulating too much power. Meanwhile, Mirkazemi was allowed to continue in government structures, becoming vice- president in Raisi's executive before being dismissed19.

Factional conflict has not only spilled over into political life, but also into relations between institutions. A paradigmatic example is the struggle between the Foreign Affairs Ministry and the Quds Force in areas critical to Iran such as the Middle East, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Its chief, General Esmail Qaani, decided in 2022 not to include foreign affairs representatives in a meeting in Najaf with Iraqi Shiite leader Muqtada al-Sadr. The effect of the meeting resulted in increased tension in Iraq between pro-Iranian Shiite and Iraqi nationalist factions and the consequence was a rift between Baghdad and Tehran20.

Media scandals are also the order of the day. For example, a possible case of corruption within the Pasdaran in 2022 was leaked to the media by releasing an audio tape in which its former chief, General Qasem Soleimani, openly discussed the issue with his generals21. Note that the news was reported by Yashar Soltani, a former candidate for mayor of Tehran in 2017 and head of the Memari News agency. Soltani was arrested in 2015 for spreading news about other possible corruption cases in Tehran, which were criticised by reformist Ali Motahari when he was vice-president of the Islamic Council22.

Given the evidence of the above cases, the appointment of the new leader is expected to be a power struggle with potentially damaging results. Far from seeking a consensual solution, what emerges is likely to be the result of an exacerbated struggle of interests over the selection of each group's candidate, dispelling the possibility of electing the most virtuous and prepared person for the position.

In the absence of an ethical code of conduct, it is quite possible to see volatile alliances supporting each other in exchange for obtaining important positions for their members within the nodes of the formal and informal power structure. Certain personal scandals, licentious behaviour or family ties may also be aired, which could detract from the credibility of the different aspirants or prevent certain endorsements for fear of falling from grace.

The enigma of potential candidates

The foreseeable contingency of Khamenei's death has been contemplated for several years. In 2019, the Assembly of Experts announced that it had established a committee two years ago to examine the most relevant people who could aspire to the leadership position. The results of their work remained secret, with only the current leader being informed23.

Prospective studies usually divide candidates into three categories in order to explore their potential. The first of would be made up of winning horses. These are individuals who have held a position of prominence in government, with a clerical status at least similar to that of Khamenei when he was elected leader, and who have experience in public office. Secondly, one could consider the long shots, made up of those aspirants who, although they do not have a great deal of experience in administration, have strong family ties, popular charisma or occupy relevant positions in important institutions. The third position in this race would be reserved for dark horses, made up of clerics who, without having great administrative experience, have shown such virtuous conduct that they have earned the affinity of Khamenei24.

Candidates to be considered in the first group include President Raisi, a ruthless prosecutor and close to the leader, with whom he shares important affinities. However, Raisi has the status of Hujjat al-Islam within the clerical hierarchy, which would place him in a middle position, and it does not appear that the leader will change this status. His position as president has also caused him significant wear and tear, losing the support of the most conservative, while reformists are directly calling for his resignation. Raisi appears to have been brushed aside by Supreme National Security Council Secretary, Ali Shamkhani, who has sidelined his foreign minister by directly taking on important issues such as restoring diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia25.

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei is head of the judiciary and also holds the clerical rank of Hujjat al-Islam. He is also close to Khamenei, as evidenced by his dismissal as intelligence minister during Ahmadinejad's second presidency, when he was at odds with the leader26. He has long distanced himself from President Raisi, expressing concern about the economic situation27. However, he has been adamant on increasing death sentences, stating that "sentences will be carried out without hesitation"28.

Another important candidate could be Sadeq Amoli Larijani, a member of an important dynasty with proven loyalty to Khamenei, despite relations with his family. His career has been highly significant as he has been head of the judiciary, a member of the Assembly of Experts and the Guardian Council, and currently chairs the Discernment Council.

Although he has an extensive administrative career and profound knowledge of Islamic law, accusations of corruption coupled with his family's loss of power undermines his credibility as a potential candidate. Given that Raisi led the investigation against Larijani, Raisi could possibly use certain information against Larijani29.

Former President Hassan Rohani is another strong contender for the leadership. His political and clerical career has been significant, including posts as secretary of the National Security Council, nuclear negotiator and member of the Assembly of Experts. Although he is moderate and pragmatic, he has always been in line with Khamenei's provisions, but lost the leader's support after former US President Donald Trump abandoned the nuclear deal secured by the Obama administration30.

Second-tier candidates could include the son of the leader and son-in-law of former parliamentary speaker Gholamali Haddad Adel. His status in the clerical hierarchy is not that of Hujjat al-Islam but only ajund, which is considered a basic level. A track record in the administration of little significance detracts from his credibility. Moreover, being Khamenei's son is detrimental to his nomination because his appointment would be a source of disintegration and confrontation within the regime itself. Nevertheless, Mojtaba has facilitated the actions of his father and his followers, placing in a position of shadow power that has had a far-reaching influence on Iranian political life31. Today, the leader's son heads his office, comprising more than 4,000 members, from which day-to-day affairs in Iran are controlled through two power nodes. The intelligence node on one hand, which coordinates 17 agencies and the propaganda body, and the influence node on the other, which is in charge of Friday prayers32.

In view of the above facts, the leader's son does not appear to be in an advantageous position to win the nomination, but such is his significance in the shadows that any power group will have to count on his support.

Another possible candidate in this category could be Hasan Khomeini, grandson of the first leader and from another important lineage. He has devoted most of his life to religious issues and in 2016 tried to run as a candidate for the Assembly of Experts. However, his candidacy was rejected by the Guardian Council33. This may have been caused by Khomeini's reformist character and his participation in the 2009 uprisings, following the second election victory of former President Ahmadinejad, who is on the hardest line of the political spectrum34. In the wake of the protests following the death of Mahsa Amini, in early 2023 Khomeini declared himself in favour of dialogue in order not to lose social support, although he acknowledged that there are forces that want to overthrow the regime and that the solution is a return to the principles of the Islamic revolution35.

Ayatollah Seyed Ahmad Khatami, who was appointed to the Constitutional Council upon the death of Ayatollah Yazdi, can also be included in this second group. He has held prominent positions as a member of the Assembly of Experts but has no experience in the field of administration and has always positioned himself against reforms, within the conservative hard line. With regard to the latest demonstrations, at the end of 2022 he called for the "toughest punishments" against troublemakers36.

Another possible member of this second option could be Ayatollah Alireza Arafi, who has a broad academic and religious profile and is a member of the Guardian Council. However, his lack of experience in administration is also a stumbling block to his possible election37.

As third options, candidates could be considered who, without starting from advantageous positions, could turn the situation around in a scenario of deadlock between power factions and counterweights. These possible candidates include the popular Hujjat al-Islam Mohammad Ali Ale-Hashem38.

Conclusions

Succession in Iran is a matter of deep concern given the regime's evolution towards a fourth stage, in which many of its future leaders have not been directly involved in the Islamic revolution and there are a number of tensions within the regime itself, with reformists and fundamentalists reaching positions that are difficult to reconcile. Khamenei has also granted extensive religious, political, economic and cultural powers to the Pasdaran, who will represent an important decision-making group in addition to the factions vying for their respective power quotas. Add to this a new generation of Iranians who did not experience the revolution or the war against Iraq and who are clamouring for greater freedoms and social rights.

Should the power mix opt for a fundamentalist-oriented cleric, the transition would be quicker and less disruptive to the Iranian governance system. In this case we could contemplate the possible options of Ebrahim Raisi or Mojtaba Khamenei, but neither can count on strong initial support.

The future leadership of either two would entail a continuation of Khamenei's policies, though possibly from weaker positions, due to waning popular support and pressure from other power groups. In this situation, the new leader would have to seek sustenance from the Pasdaran, who are already sufficiently empowered by Khamenei's need for support. Further accumulation of power in the hands of the Pasdaran could constitute a counterweight to the new leader’s authority.

Another less likely option is for a moderate or reformist cleric to become supreme leader. In this case, candidates such as Rohani or Khomeini could be considered. While popular support for this option is likely to increase, the power system would suffer greatly, as it would be opposed by fundamentalists and Pasdaran.

An additional possibility is that no consensus could be reached and the appointment of the leader could be delayed, thus avoiding direct disputes and allowing time for negotiations between power groups. Even if rival factions were to be appeased, it would lead to a stalemate in decision-making at a time when the world is changing rapidly, and the Iranians could lose leverage if they are unable to gain an advantageous position in the international system. Likewise, the lack of guidelines could eventually affect the economic and social well-being of the country, leading to situations of popular discontent.

A variant of the possibility described above could be the formation of a triumvirate or interim diarchy, as was envisaged during the decision-making process that brought Khamenei to leadership. Mixing representatives from various factions would not be the ideal solution, but it would at least allow the most important decisions for the country's progress to be taken. However, the weakness of this collegiate body vis-à-vis the Pasdaran would give the latter a strong ability to influence the most important decisions on Iran's future. Given the nature of this organisation, Iran is likely to pursue a more aggressive and expansive policy in the regional arena.

Another variant to the lack of consensus could come from confrontation between the different factions, including the possibility of violence. In that case, the Pasdaran could be the element that pacifies Iranian public life, but again their share of power would be increased vis-à-vis the other factions.

In any case, and given the power wielded by the Pasdaran family, it would not be out of the question that a military officer with great prestige within this group might surprise us with his appointment. While Qasem Soelimani may have been the most charismatic figure in the past, his replacement in the Quds Force, Esmail Qaani, is also prestigious and has many supporters.

Finally, the more remote possibility of a regime change should be considered. Although Iran has evolved since the time of the Islamic revolution, it seems that Iranian society is not yet ready for it and the revolutionary system still has a sufficiently robust structure to prevent this from happening.

Whatever happens, the change of leader scenario will be a critical phase for Iran at a geopolitical time when it cannot afford to make mistakes or miss opportunities. Regardless of the new leader’s orientation, the major lines of Iran’s long-term strategy are expected to be maintained.

José Ignacio Castro Torres*

COR. ET. INF. DEM

PhD in Peace and International Security Studies

IEEE Analyst

References:

1 FASSIHI, Farnaz. Iran's Supreme Leader Cancels Public Appearances After Falling Ill’, The New York Times. 16 Sept. 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/16/world/middleeast/irans-supreme-leader-ayatollah-ali-khamenei- ill.html (accessed 01/08/2023)

2 IRAN INTERNATIONAL. ‘Khamenei's Chief Of Staff Denies Rumours Of Ill Health’. Tuesday, 7/11/2023. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202307119739 (accessed 02/08/2023)

3 WINCHESTER, Nicole. ‘Protests in Iran: Death of Mahsa Amini’, In Focus. House of Lords Library. 21 October 2022. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/protests-in-iran-death-of-mahsa-amini/#heading-3 (accessed 08/08/2023)

4 For an evolutionary follow-up of the social protests in Iran, we suggest reading CASTRO TORRES, José Ignacio. Ten years of the Green Movement in Iran. IEEE Briefing Paper 14/2019. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_informativos/2019/DIEEEI14_2019CASTRO-VerdeIran.pdf (accessed 08/08/2023)

5 HRANA, Human Rights Activists news agency. ‘Woman, life, freedom; Comprehensive report of 20 days of protest across Iran’. 12 October 2022. https://www.en-hrana.org/woman-life-freedom-comprehensive-report-of-20-days-of- protest-across-iran/ (accessed 08/08/2023)

6 SAMMY, Dana. ‘Anti-Government Demonstrations in Iran. A Long-Term Challenge for the Islamic Republic’, The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). 12 April 2023. https://acleddata.com/2023/04/12/anti- government-demonstrations-in-iran-a-long-term-challenge-for-the-islamic-republic/ (accessed 08/08/2023)

7 SARIOLGHALAM, Mahmood. ‘Diagnosing Iran's emerging pivot toward Russia and China', Middle East Institute. 1 June 2023. https://www.mei.edu/publications/diagnosing-irans-emerging-pivot-toward-russia-and-china (accessed 08/08/2023)

8 THE IRAN PRIMER. ‘Raisi: Profile of President-elect’. 20 July 2021. https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2021/jun/21/profile-president-elect-ebrahim-raisi (accessed 09/08/2023)

9 BENÍTEZ, Juan Carlos. ‘Ali Khamenei's Succession Within the Iranian Political Framework’, The Geopolitics (TGP). 19 December 2021. https://thegeopolitics.com/ali-khameneis-succession-within-the-iranian-political-framework/ (accessed 09/08/2023)

10 Twelfth imam or mahdi. Messianic leader who will come at the end of time to restore justice and religion.

11 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran 1989. Iran Chamber Society. https://www.iranchamber.com/government/laws/constitution.php (accessed 09/08/2023)

12 Ibid.

13 AL MANAR. ‘General Qaani: Irán impidió que EE. UU. estableciera su control sobre la región de Asia Occidental’. 23 February 2023. https://spanish.almanar.com.lb/729808 (accessed 12/08/2023)

14 HAGHIGHATNEJAD, Reza. ‘Montazeri and the Men who Mattered: Iran Then and Now’, IranWire. 16 March 2016. https://iranwire.com/en/features/61942/ (accessed 10/08/2023)

15 UANI, United Against Nuclear Iran. ‘Who Will Be Iran's Next Supreme Leader?’ November 2021. p. 3. 16 BBC News. ‘Iran How Ayatollah Khamenei became its most powerful man’. 9 March 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-29115464 (accessed 10/08/2023)

17 ESHRAGHI, Ali Reza. ‘Iran's Coming Succession Crisis. The Race to Be the Next Supreme Leader Will Be Chaotic and Perilous’, Foreign Policy. 24 May 2023. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/iran/irans-coming-succession-crisis (accessed 10/08/2023)

18 RADIO FREE EUROPE. ‘Ahmadinejad Rebuked Over Oil Ministry Grab’. 20 May 2011. https://www.rferl.org/a/ahmadinejad_rebuked_cabinet_appointment/24181087.html (accessed 10/08/2023) 19 AMWAJ.MEDIA. ‘Amid rising criticism over economy, Iran's president shakes up cabinet’. 21 Apr. 2023.

https://amwaj.media/media-monitor/amid-rising-criticism-over-economy-iran-s-president-shakes-up-cabinet (accessed 10/08/2023)

20 DAVISON, John and RASHEED, Ahmed. ‘Rift between Tehran and Shi'ite cleric fuels instability in Iraq’, Reuters. 23 Aug. 2022. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/iraq-iran-shiites/ (accessed 10/08/2023)

21 IRAN INTERNATIONAL NEWSROOM. ‘Hard To Deal With Massive Corruption In Iran, Says Whistleblower’. Monday, 31/10/2022. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202210317807 (accessed 10/08/2023)

22 BBC News Persian. ‘یلع یرهطم زا همادا تشادزاب راشای ،یناطلس ریبدرس یرامعم زوین داقتنا درک / Ali Motahari criticó el arresto continuo de Yashar Soltani, el editor de Memari News’. 15 October 2016. https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran- 37665917 (accessed 10/08/2023)

23 RADIO FARDA. ‘Influential Ayatollah Says No One Designated To Succeed Khamenei’. 27 January 2019. https://en.radiofarda.com/a/iran-ayatollah-says-no-one-designated-to-succeed-khamenei/29734096.html (accessed 11/08/2023)

24 UNITED AGAINST NUCLEAR IRAN. ‘Who Will Be Iran's Next Supreme Leader?’ Op. cit., p. 4.

25 STIMSON CENTER. Raisi fails to boost Mojtaba Khamenei's chances of becoming Iran's next Supreme Leader. 12 April 2023. https://www.stimson.org/2023/raisi-failures-boost-mojtaba-khameneis-chances-of-becoming-irans-next- supreme-leader/ (accessed 11/08/2023)

26 SANCHEZ, Alba. ‘El conservador Mohseni Ejei, nombrado nuevo jefe del poder judicial iraní’, Atalayar. 1 July 21. https://www.atalayar.com/articulo/politica/conservador-mohseni-ejei-nombrado-nuevo-jefe-poder-judicial- irani/20210701162545151907.html (accessed 11/08/2023)

27 CRITICAL THREATS. ‘Iran Crisis Updates, January 2023’. 31 January 2023. https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-crisis-updates-january-2023 (accessed 11/08/2023) 28 DAWI, Akmal. ‘Rights Group: Iran Executed 142 People in May’, VOA News, 01 June 2023.

https://www.voanews.com/a/rights-group-iran-executed-142-people-in-may/7119143.html (accessed 11/08/2023)

29 United Against Nuclear Iran. ‘Sadegh Amoli Larijani Chairman of Iran's Expediency Council’, UANI. 3 August 2023. https://www.unitedagainstnucleariran.com/sadegh-amoli-larijani-chairman-of-irans-expediency-council (accessed 11/08/2023)

30 FRANCE24. ‘Iran's Khamenei says experience shows “trusting West does not work”’. 28 July 2021. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210728-iran-s-khamenei-says-experience-shows-trusting-west-does-not- work (accessed 11/08/2023)

31 GOLKAR, Saeid and AARABI, Kasra. ‘Why Khamenei is unlikely to pick his son to succeed him as Iran's supreme leader’, Middle East Institute. 21 September 2022. https://www.mei.edu/publications/why-khamenei-unlikely-pick-his- son-succeed-him-irans-supreme-leader (accessed 11/08/2023)

32 BUCHTA, Wilfried. ‘Will Khamenei's Son Play a Role in Iranian Succession?"’ The Washington Institute. 7 Apr. 2021. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/will-khameneis-son-play-role-iranian-succession (accessed 11/08/2023)

33 THE GUARDIAN. ‘Reformer Hassan Khomeini barred from Iran clerical body ballot"’ 26 Jan 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/26/iran-reformer-hassan-khomeini-barred-assembly-experts-ballot (accessed 11/08/2023)

34 LIM, Kevjn. ‘Iran The Ayatollah Succession Question’, The Diplomat. 11 October 2014. https://thediplomat.com/2014/10/iran-the-ayatollah-succession-question/ (accessed 11/08/2023)

35 ASHARQ AL-AWSAT. ‘Khomeini’s Grandson Warns against Regime Popular Base Shrinking’. 29 January 2023. https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/4125866/khomeini%E2%80%99s-grandson-warns-against-regime-popular- base-shrinking (accessed 11/08/2023)

36 IFMAT. ‘Seyyed Ahmad Khatami Info’. https://www.ifmat.org/03/20/seyyed-ahmad-khatami/ (accessed 11/08/2023) 37 VATANKA, Alex. ‘The Islamic Republic's next generation of leaders: A profile of Alireza Arafi’, The Middle East Institute. 6 July 2020. https://www.mei.edu/publications/islamic-republics-next-generation-leaders-profile-alireza-arafi (accessed 11/08/2023)

38 IRAN FRONT PAGE. ‘Popularity of Iranian Friday Prayers Imam Growing in Tabriz’. 17 March 2018. https://ifpnews.com/popularity-of-iranian-friday-prayers-imam-growing-in-tabriz/ (accessed 11/08/2023)