The war over water

In the past, we have discussed the problems that threaten the already ‘shifting’ situation in East Africa, a region plagued by political instability, extreme poverty and the rise of jihadist terrorism.

Unfortunately, one of the reasons for many of these problems is water scarcity, a factor that many analysts, and even official reports from agencies such as the US State Department, have long pointed to as the main potential cause of conflict in the medium-term future. Perhaps that window of opportunity has now closed.

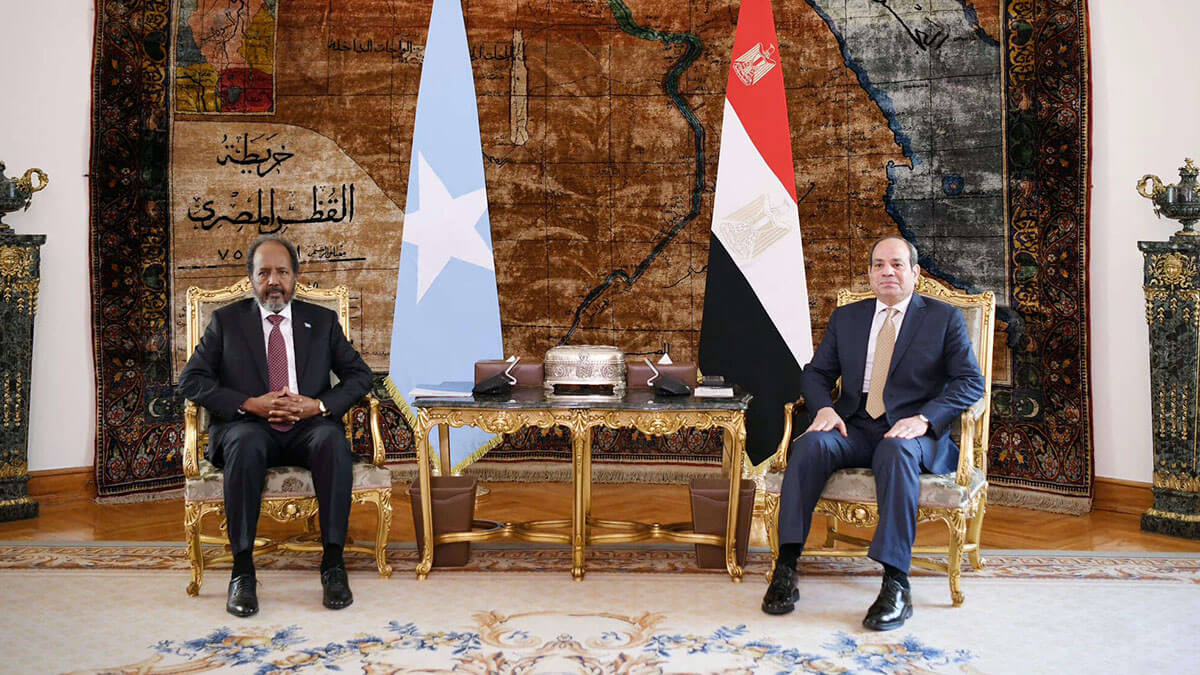

At the end of last month, news broke that Egypt had, after four decades of not having done so, made its first military aid action to Somalia in the form of arms deliveries. This set off alarm bells, as the obvious consequence of this action is a worsening of tensions between the two countries and Ethiopia.

The explanation for this long-standing rapprochement between Egypt and Somalia can be found in Ethiopia's signing of a preliminary agreement with the breakaway region of Somaliland to lease coastal land to secure a sea outlet in exchange for possible recognition of its independence from Somalia.

This move is not something that has been decided at random. It comes in an attempt to take advantage of Somalia's status as a failed state and against the backdrop of regional tensions over water resources. The Mogadishu government was quick to describe the agreement as an attack on its sovereignty, and subsequently stated its intention to use all necessary means to block it.

But at the root of this three-way confrontation lies a more important issue, which is forcing those involved to seek alliances, support and ways to weaken their opponent. And that issue is related to access to water, which is key to the region's economy and development.

Egypt has been at loggerheads with Ethiopia for years over Addis Ababa's construction of a large hydroelectric dam at the headwaters of the Nile River, known as the ‘Grand Renaissance Dam’, an engineering feat that could be described as pharaonic. It is this confrontation that has led him to condemn the Somaliland deal.

His way of materialising this disagreement was to sign a security pact with Mogadishu, offering, in addition to military equipment, to send troops to a new peacekeeping mission in Somalia.

It is clear to no one that this is yet another step in the escalation between the two countries (Egypt and Ethiopia), whose tensions, as we have mentioned, stem from the construction of the dam. The hostility, which has been simmering for years, could erupt on Somali soil, and that is what makes the situation more than critical, for the prospect of a war fought not on the soil of either country but on that of a third is often a spur to combat, as it would not be the population of either country that would suffer the consequences.

But let's put the real reason for the conflict into perspective: how has the issue of the Grand Renaissance Dam evolved in recent years?

Ethiopia defends the construction of the dam as an essential action that will kick-start the engine of its economic development. Indeed, the facility has the capacity to generate more than 5,000 megawatts of electricity. However, the Egyptian government has expressed concern about the impact that the filling of the dam may have on its access to water, especially in times of drought.

The dam, which has been under construction for more than a decade, has been the subject of controversy because of its potential impact on the flow of the Nile, on which Egypt and Sudan rely heavily for their water resources. Despite attempts at mediation by the African Union, and although talks between the three countries have yielded small glimpses of progress or possible agreements, substantive negotiations have been stalled for two years.

In 2011, the Ethiopian government announced the start of construction work on what it called the ‘Grand Renaissance Dam’. Work began unilaterally and without the consent of the riparian countries, Egypt and Sudan, which would clearly be affected in one way or another by their dependence on the waters of the Nile. This unsurprisingly led to early tensions in the region, especially with Egypt, which depends on the Nile for more than 90% of its water supply.

In an attempt to ease tensions, Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan signed a preliminary agreement in 2015 with a declaration of principles setting out the principles of cooperation and understanding on the use of the Nile. The agreement noted the need for technical studies and assessments on the impact of the dam.

These studies were delayed despite the fact that construction continued to progress, which made the negotiations between the three parties so difficult that Egypt accused Ethiopia of moving forward unilaterally without taking into account the concerns of the other countries. At this point, by 2018, the negotiations could be considered to have failed.

Even without any agreement with Egypt and Sudan, in mid-2020, Ethiopia announced the first filling of the dam. Egypt took the case to the UN Security Council, arguing that Ethiopia's unilateral action posed a threat to its water security and regional stability. However, Ethiopia countered by declaring that it has every right to use its natural resources as it sees fit to contribute to the country's development.

In 2021, the African Union stepped in and tried to mediate between the parties, but negotiations failed again in the face of Ethiopia's intransigent position and unilateral actions that materialised in the second filling of the dam. This increased tension with Egypt and Sudan, which issued communiqués warning of the consequences for water flow and access to water resources, and the implications for their respective economies. This was something they could not allow.

The fourth filling of the dam was completed in 2023, marking the beginning of the final phase of this ambitious project, which again raised tensions mainly with Egypt. None of the attempts at negotiation or mediation yielded positive results. It was then that Egypt decided to take stronger measures.

It was in January of this year that diplomatic tensions soared when Ethiopia announced the beginning of the filling of the fifth basin, bringing the project inexorably closer to full completion.

Egypt's response was swift and in February it announced its commitment to participate in the African Union Stabilisation and Support Mission (AUSSOM) in Somalia, which is the mission that will replace the current AU peacekeeping mission at the end of 2024. This move had consequences for Ethiopia, which saw the dam issue continue to seriously undermine its relations with Egypt.

Last August saw another flashpoint in the deteriorating situation when Somalia threatened to expel Ethiopian troops stationed on its territory if Ethiopia did not revoke its agreement with Somaliland. Egypt, seeing the possibility of increasing pressure on Ethiopia, reiterated its support for Somalia and its rejection of the Ethiopia-Somaliland agreement, reaffirming its willingness to defend Somalia against any external threat.

Egypt has taken advantage of these tensions to strengthen ties with Somalia, seeking to counter Ethiopia's influence in the region and reinforce its position in the conflict over the Grand Renaissance Dam.

There are several key points to understand what is happening. On the one hand, Egypt's dependence on the Nile accounts for almost all of the country's water supply. Added to this is Ethiopia's unilateral attitude, which sees the dam as a great opportunity to initiate an economic take-off after decades of misery.

It is this need that has led it to act without waiting for the conclusion of negotiations. The enormous subordination of both countries to the river is the reason why any kind of mediation has failed. And finally, there is the impact on Sudan, which is also affected, but whose current internal situation puts it in a weak position, although its position has always been supportive of Egypt.

The conflict over the Renaissance Dam has remained unresolved for more than a decade. With each filling phase, tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt have intensified, and there seems to be no prospect of a clear diplomatic solution. The next filling phases of the dam, especially in critical times such as drought, will be decisive in the evolution of this regional conflict, which is based on access to water, but which can drag in other countries such as Somalia, and which those really affected by the problem seem determined to use as a ‘playing field’, thus increasing the instability of a region in which there is no shortage of problems and whose development can have very serious consequences for everyone.