InCels and the emergence of possible misogynist terrorism

InCel violence represents a great danger

For some years now, the media, academia and the security world have been reporting on a new and growing threat to society: InCel extremism. The essence of this ideology is a disastrous cocktail of misogyny, frustration and obsession with physical attractiveness, the result of repeated failure to establish social and romantic relationships with women. Although misogyny and sexual frustration are not unknown phenomena, new media and online spaces have promoted the emergence of new expressions of misogyny, such as the very emergence of InCels.

InCel ideology is an excellent example of new radical narratives that challenge traditional images of extremism and terrorism. Despite its global reach and almost exclusively online, InCel-related mass killings have resulted in 74 deaths since the first massacre officially linked to InCel extremism in 2014. The increased lethality of their actions and the apparent mimicry of the modus operandi of other violent extremism has put the debate over whether InCel violence should be categorised as acts of terrorism on the table.

Involuntary Celibates or more commonly known as InCels (Involuntary Celibates) are an online community of mostly heterosexual men with little or no ability to establish successful sex-affective relationships with women. For the self-described InCels, the assumption of biological determinism, women's preferences and the prevailing unjust social structures have established themselves as the leitmotif of their sentimental failure and the cornerstone of their radical narrative1.

The first time the InCel concept appeared publicly under this very name coincides with the advancement and democratisation of internet access. In 1997 a Canadian student created an online forum dubbed the "Involuntary Celibacy Project". In the beginning, it was intended to be a "friendly"2 and mutually supportive place that brought together those who, regardless of gender, were single, had never had sex or had not been in a relationship in a long time3.

It was simply a space in which to share their frustrations and difficulties in developing social and/or romantic relationships. Over time, however, the forum became a more twisted space and was overshadowed by endemic misogyny, violent sexual iconography, rancour and sexual frustration. Sympathisers and supporters of male supremacy, stemming from what academics referred to as the Manosphere, appropriated the concept, imbuing it with radical and violent undertones. The commission of the first attack by a self-proclaimed InCel (Elliot Rodger), the 20144 Isla Vista Massacre, revealed the perversity of violent InCel ideology, and in subsequent years, unleashed the perversity of violent InCel ideology, and in subsequent years, unleashed a series of commensurate attacks by other InCel sympathisers.

In the academy, the Manosphere is referred to as an uncompromising and radical by-product of the 1970s Men's Liberation Movement of vigorous opposition to the rise of second-wave feminism5. Despite the ideological plurality of these groups, which include Men's Rights Activists (MRAs), Pick Up Artists (PUAs), Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOWs) and Involuntary Celibates (InCels), their common denominator is discord with feminism, hostility to women and the Red Pill philosophy6.

The Red Pill doctrine is inspired by the well-known scene from the science fiction film 'The Matrix' (1999). In InCel jargon, taking the Red Pill is equivalent to an awakening that presupposes the revelation of the reality world. Specifically, it refers to an awareness of both the frivolous nature of women and the feminist yoke, which in their view "has robbed them of their right to a wife and sex"7. They are thus convinced that the real victims of gender oppression and discrimination are, in reality, men8. Therefore, the symbolic act of taking the Red Pill is ultimately the appropriation of a new set of antithetical beliefs that can become the trigger for a process of radicalisation9.

But beyond the Red Pill and the Blue Pill, which represents ignorance or unawareness of this supposed reality, the InCels have popularised a third and more extreme one: the Black Pill, a cruel epiphany about the unchangeability of reality. Simply put, it puts an end to any aspiration to escape their involuntary celibate status, which by default condemns them to the bottom rung of the social hierarchy. As a consequence, they believe that any attempt at improvement is futile and that it is only possible to break the immutability of this social stratification through changes at the societal level. In practice, however, there is no evidence of peaceful offline activism to promote social change10.

Broadly speaking, the InCel community can be divided into three main groups: those who simply subscribe to the literal meaning of Involuntary Celibates, those who believe in the pill theory, and adopt the radical Red Pill perspective, and those who also take the Black Pill.

While the Red Pill narrative displays the classic characteristics of a radical worldview, a combination of grievance, victimisation, blaming and a polarised perception between the ingroup (us) and the outgroup (them). The Black Pill, broadly speaking, adds more radical indicators that are identified as attributes of violent extremism such as glorification and incitement to violence, violent and hostile rhetoric (hate speech) and actual acts of violence.

Thus, the InCel community must be considered as a spectrum, as they do not form a uniform social and political body. Sylvia Jaki et al. highlighted the heterogeneity of both profiles (nationality, age, economic situation, educational level etc.)11 and ideological convictions. As a result, it is a space where more or less radical, hostile and violent opinions converge.

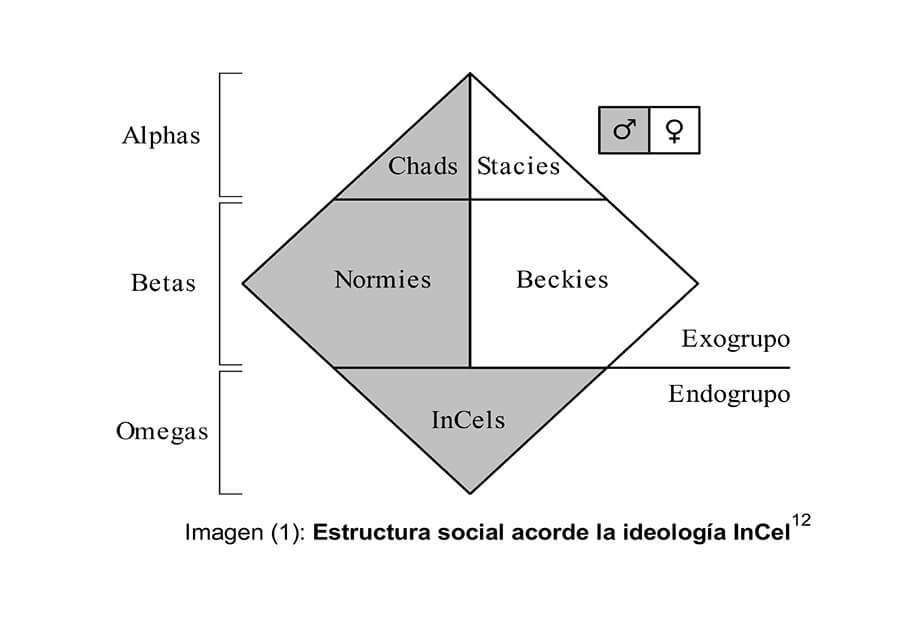

In the InCel imaginary, society is structured in a heteropatriarchal (not pyramidal) three-tiered hierarchy (Figure 1). Substantial aspects of the subsequent categorisation are based on prejudices and stereotypes corroborated with subjective reinterpretations of disciplines such as biological determinism and evolutionary psychology. The conclusions drawn from their own research often fall into confirmation bias as they tend to support their convictions and reinforce their sense of grievance and victimisation. The crux of their hierarchisation highlights their obsession with physicality that is intertwined with racism and class. Thus, race and economic status are additional qualities that add or subtract value in the sexual marketplace and thus impact on the respective categorisation.

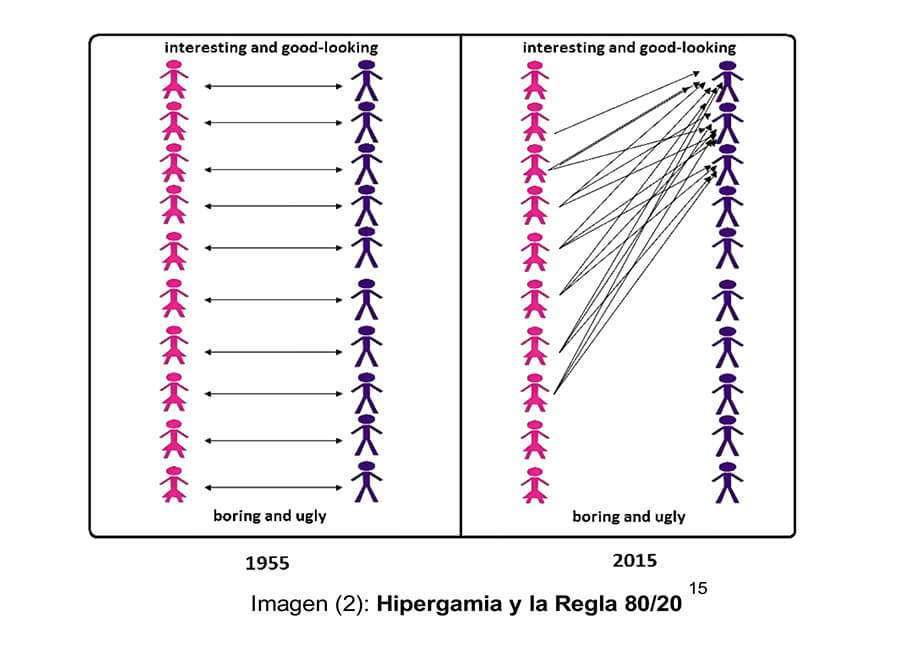

At the top of the hierarchy are the "Chads" or "Alphas", a minority of cisgender, charismatic, wealthy and sexually successful men among women. They represent an idealisation of virility typical of what is known in gender studies as hegemonic masculinity13. Because of their privileged position, Alphas have access to most women, creating sexual inequality. Some radical InCels corroborate this impression with a socio-Darwinian adaptation of the 80/20 Rule (Pareto Principle) in combination with the supposed natural tendency of women to practice hypergamy. Thus they believe, as illustrated in Figure 2, that Chads make up only 20% of the population and that 80% of women are exclusively interested in these men of equal or higher status than themselves14.

Although Chads are considered Caucasian by default, within this category, racial subcategories are established with their respective terminology, for example "Changs" for those of Asian origin, "Gaston" for French and "Chadriguez" for Latin Americans. Ethnic variations also establish nuances that play into racist clichés, for example, the label "Tyrone", which refers to a dark-skinned Chad, is associated with stereotypes about African Americans that date back to the colonial era, such as hypersexuality. In fact, InCels use the acronym "JBW" ("Just Be White") to emphasise the advantage of white men over other ethnicities in their respective sexual success16. However, the violent racist discourse has proven to be rather ad hoc17. The female counterpart of a Chad is called Stacy who corresponds to traditional beauty standards: blonde, Caucasian, attractive, etc.

The next category down is the majority of the male population, the "Normies" or "Betas", ordinary people with a standard social and sexual life. The equivalent for women is "Becky". Finally, in the last social stratum are the InCels or "Omegas". Among the InCels there is also a subdivision in terms of ethnicity, e.g. "Rice-cel" refers to an InCel from Southeast Asia or "Currycel" to an InCel from India. Unlike the other strata, this category, from their perspective, does not have a female counterpart because of their belief that involuntary celibacy among women is impossible and that any woman, regardless of her physical appearance, can find a partner. However, there are women who identify themselves as "Femcel"18.

Their self-identification as a minority and the lowest point in the social hierarchy provides an ideal rationale for the construction of a narrative that emphasises their position as victims, from which bridges can easily be established for the blaming and consequent definition of the target of their hatred.

In this way, they establish a psychosocial distinction of reality in dichotomous terms, between victims and perpetrators, between the in-group (InCels) and the out-group (Chads, Normies, Stacys and Beckys). This antagonism favours the creation of their own identity, which is artificially constructed on the basis of the othering of the "others" - it is the "us" and the "them".

In the same vein, this binarism between ingroup and outgroup, in conjunction with perceived suffering, provides the more extremist InCel subspace with a solid legitimisation for violence against their external targets19. In this polarised scenario, InCels portray the ex-group, especially women, in a highly negative light, whom they, along with feminism, point to as being to blame for their situation and deserving of their hatred. But unlike other radical groups and ideologies that construct their group identity in positive terms, InCels default to a degrading and demeaning self-image20 and "a shared sense of inferiority"21.

The dehumanisation of women, often referred to as "foid" or "femoid" (Female - woman and Humanoid - humanoid) or "roasties", is common in discussions. Women are described as intellectually inferior people who are guided exclusively by the most basic instincts and emotions. Overall, the very figure of the woman is sexually objectified and reduced "to her physical appearance, sexuality or individual body parts"22.

This denaturalisation of women allows them to rationalise and justify their misogyny and in turn, legitimise "the right of men to oppress them"23. Dehumanisation and objectification have a disinhibiting effect by denying humanity. It is, therefore, the perfect combination for the nullification of empathy.

Their self-identification as true victims translates into demands and yearnings to subvert this perceived unjust situation. As a result, some evoke or express a certain nostalgia for an earlier patriarchal society, where the male gender guaranteed them a more privileged position. Many believe that they have a natural right to sex, and even to women, which is being violated24.

This feeling of injustice plays a fundamental role, for as R. Kalish and M. Kimmel underlined, "the wronged right is a gendered emotion, a fusion of that humiliating loss of manhood and the moral obligation and right to regain it"25. Thus, some call for the abolition of women's rights and freedoms such as the right to vote, the free choice of partner(s) or the restoration of monogamy as a general rule.

At their extreme, some radical InCels go beyond moral-ethical limits, calling for a kind of dystopian reality through threats and fantasies: the introduction of capital punishment for women for adultery, the subsidising of prostitution, the physical confinement of women26, sexual slavery27, the legalisation of rape or the introduction of what they call Sexual Marxism (the redistribution of sex)28.

However, there is a significant fraction of users who actively oppose these views and reject violence and who, above all, oppose the most extreme expression of this hatred: the commission of massacres. Some even agree that the problem with InCeldom's increasingly radical environment and the bad reputation of the Involuntary Celibates is the spread of the ideology of the macabre Black Pill.

Often, from their posts, it is difficult to differentiate those messages that are expressions of pure venting of rage, anger and frustration, those posts that are the result of what is known as "trolling" or "shitposting" - the act of posting absurd, surreal, aggressive and ironic (low quality) content online, sometimes in order to provoke a reaction29 - from those that are a real threat30.

This almost hermetic environment can function as echo chambers that can reinforce hatred and extreme views, especially about women. As a result, users sometimes share offensive and/or aggressive comments that ignite an exacerbated maelstrom of increasingly extreme and outlandish retorts and replies.

While shitposting can constitute a kind of false direct threat, it can also "contribute to radicalisation and, ultimately, mobilisation"31. But even regardless of the original intent of such posts, such content can still be considered dangerous speech, knowingly increasing the likelihood of an adverse response against individuals32.

For some experts such as Jacob Ware, associate fellow for counterterrorism at the Council on Foreign Relations33, such incitement should be included in the category of stochastic terrorism - "the use of mass communications to incite random lone wolves to carry out violent or terrorist acts that are statistically predictable, but individually unpredictable"34. Although, the incitement to violence and emulation of previous violent acts is clearer in the manifestos of Elliot Rodger, Alek Minassian and Christopher Harper-Mercer. As the following quote from C. Harper-Mercer's manifesto illustrates: "(...) My advice to others like me is to buy a gun and start killing people. (...) To the Vestor Flanagans, Elliot Rodgers, Seung Cho, Adam Lanzas of the world, I do this. For all those who never took me seriously, this is for you. (...) I am the martyr for all those who are like me."35 .

Finally, the violent character of his ideology is reinforced by the celebration and memory of massacres linked to the InCel community or whose perpetrator shared some InCel attributes. Such a component is also evident in other extremist and even terrorist groups such as jihadists or, to a lesser extent, extreme right-wing groups36. The more radical strands of InCel ideology have engaged in a process of canonising those responsible for such crimes. The more radical InCels often refer to them as heroes (or "hERo" - after Elliot Rodger), icons, saints or patrons.

In their "virtual pantheon of InCel heroes"37 they also add criminals whose identification as InCels is not entirely certain. Yet, because of the nature, similarity (choosing women as their victims, sexual frustration, isolation, etc.) and ruthlessness of their acts, they are often referred to as InCels. ) and cruelty of their acts, these were appropriated and considered referents, such as Marc Lépine38 , author of the Massacre of the Polytechnic School of Mont-real (Canada) in 1989, Stephen Paddock39 , author of the Las Vegas Shooting of 2017 or known perpetrators of shootings in educational centres such as Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, responsible for the Columbine High School Massacre (USA)40.

In this mystification Elliot Rodger occupies a special position, as he provides the first role model for radically misogynist InCels and his Manifesto: "My Twisted World: The Elliot Rodger Story" has been considered by some to be the founding charter of the more radical InCel movement41. In fact, they have coined and popularised the expression "going ER" or "being a hERO", as a tribute to and remembrance of E. Rodger, to encourage others to imitate his actions.

The Elliot Rodger and Alek Minassain massacres and their respective manifestos sparked the first debates on the categorisation of violence linked to InCel ideology as terrorism42. For some experts, InCel ideology is considered a form of violent extremism and its violence a form of leaderless resistance, stochastic terrorism43 or domestic terrorism with a possible propensity beyond national borders44.

In 2020, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) laid terrorism charges against the minor (unidentified under the Youth Criminal Justice Act) responsible for the stabbing attack at an erotic massage parlour in Toronto. Canadian authorities concluded that the accused perpetrator "was inspired by the ideologically motivated violent extremist movement (IMVE) commonly known as INCEL"45. Such a decision is significant because it was "the first time Canada has prosecuted a terrorism-related charge unrelated to Islamic extremism and apparently the first time in the world that a country has brought terrorism charges against an adherent of the InCel movement"46.

As shown in table (1), there is continuity and a timid increase in the number of attacks since 2014. Nonetheless, violence linked to InCels is not very frequent. It is notable, however, that it has characteristics in common with terrorism. For this reason, pioneering research by Bruce Hoffman, Jacob Ware and Ezra Shapiro concluded that such crimes should be understood as an "emerging trend of terrorism with a more relevant hate crime dimension"47.

The main problem with this dilemma lies in the very indefiniteness of the concept of terrorism, but there seems to be some consensus on some of its fundamental aspects:

- Succession of attacks

- Use of violent means of mass intimidation.

- Specific purpose (some definitions are more specific, referring to a political, religious and/or ideological reason).

According to these three factors, some violent actions attributed to the InCels, such as the case of the young minor (2020) mentioned above, can be considered acts of terrorism. In contrast, the case of Alek Minassian (2018), one of the deadliest, was not prosecuted for terrorism. For despite A. Minassian's apparent link to the InCel ideology by the short post on his Facebook profile (see quote) during the attack, the verdict concluded that A. Minassian rather took advantage of the InCel ideology to increase his fame and benefit emotionally from the hero image that the InCel community would bestow on him60.

"Infantry Private (recruit) Minassian 00010 wishes to speak to Sergeant 4chan, please. C23249161. The Incel rebellion has begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys. All hail the supreme knight Elliot Rodger!"61

Thus, there was no apparent ideological, political or religious motivation behind the crime, but as the verdict itself determined "it is almost impossible to know when Mr. Doe [A. Minassian] is lying and when he is telling the truth. Determining his exact motivation for this attack is also nearly impossible"62. Although he does occasionally refer to A. Minassian as a terrorist63.

In the same vein, the reason why the case of Sheldon Bentley (2018) was not treated as terrorism is even more evident. The motivations that led S. Bentley to commit such a crime cannot be attributed solely to his involuntary celibacy64, but was rather an impulsive act. Finally, and perhaps most paradigmatic is the case of Elliot Rodger (2014). The perpetrator of the Santa Barbara Massacre has not been officially categorised as a terrorist, yet he is an illustrative case of misogynistic InCel terrorism.

There is no doubt about his motivations: the idealisation of a "pure world where sexuality did not exist"65 under an authoritarian rule that is far from the ideals of liberal democracy. In the massacre perpetrator's own words, "If I can't have it, I will do everything I can to DESTROY it."66 . Even more substantial is his hatred of women for denying him their right to have sex-affective relationships and his intention to cause harm to sexually successful women and men. Also, their intention to provoke terror and intimidate the population with the promised "Day of Retribution"67 and the declaration of the "War on Women"68.

However, it would be a mistake to jump to conclusions and wrongly label the entire InCeldom spectrum as terrorist. Clearly, neither will most InCels commit such crimes, nor do all InCels, as noted, condone or celebrate the attacks. Establishing a direct link between InCels and violence, extremism or terrorism may lead to their stigmatisation as a far from homogenous group and could have a counterproductive effect.

The decision to label InCel violence as an issue of terrorism has certain implications, which have called into question the actual effectiveness of dealing with the InCel phenomenon. Terrorism, broadly speaking, alters the way in which law enforcement prevents, investigates and punishes attacks, as well as the funding for such efforts. On the other hand, and in this particular case, the specificity of the InCel imaginary must be taken into account, such as the preponderance of psychological disorders or the difficulty to identify with any certainty who is part of the group and who is not.

Furthermore, the InCel online ecosystem is mostly filled with gibberish, irony and sinister fantasies ("shitposting") that make it difficult to decipher the real threat. This can result in the identification of false alarms and the wasteful expenditure of time, effort, human and financial resources. Indeed, treating misogyny and sexual frustration as exclusively distinctive elements in identifying InCel violence can overshadow the extent of male supremacism present in other groups, which encourages the subjugation of women, virulent anti-women rhetoric and sometimes instigates violence69.

But beyond the possible solution to this dilemma, neither the potential of their ideology, their capacity to radicalise, nor the massacres that some extremist InCels have carried out, should be trivialised. Thus, it is reiterated, they represent a potential emerging threat that must be taken seriously. As emphasised in the Texas Department of Public Safety's Domestic Terrorism Threat Report (2020), "the violence demonstrated by InCels over the past decade, coupled with the extremely violent rhetoric online, suggests that this particular threat could soon match, or potentially eclipse, the level of lethality demonstrated by other types of domestic terrorism"70.

In conclusion, the dangerousness of InCel ideology is ambiguous but, as evidenced, it exists. And while terrorism linked to this movement is rare, it is indisputable that this online ecosystem is a radical environment, whose users exhibit clear vulnerability factors that make them potentially susceptible to radicalisation.

In Europe, violence linked to InCels is already a fact, although unusual. In the specific case of Spain, the InCel phenomenon has hardly been studied; however, the presence of InCel discourse in well-known Spanish forums such as "Forocoches" and "Foroparalelo"71 has been demonstrated. Likewise, specific InCels forums, with an international audience and participation, host publications in Spanish, discussions on the political situation in Spain or users who directly confirm their Spanish nationality.

Laura Illa Vidal, Master in Prevention of Radicalisation and collaborator in the area of Armed Conflict and Terrorism Prevention at Sec2Crime.

BIBLIOGRAPHY :

1 Moonshot, “Incels: A Guide to Symbols and Terminology”, 2020, disponible en: https://moonshotteam.com/incels-symbols-and-terminology/.

2 TAYLOR, Jim, “Los remordimientos de la mujer que fundó el movimiento Incel de "célibes involuntarios", vinculado a la muerte de varias personas en Canadá y EE. UU”. BBC News, 31.08.2018, disponible en: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-45355326.

3 Ídem.

4 “Elliot Rodger: How misogynist killer became 'incel hero'”, BBC News, 26.04.2018, disponible en: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-43892189.

5 LABBAF, Farshad, “United by Rage, Self-Loathing, and Male Supremacy: The Rise of the Incel Community”, Gender, Colonization, and Violence. Invoke Vol. 5, pp. 16-25, 2020.

6 ISLA JOULAIN, Gabriel Luis, “Célibes Involuntarios: ¿Terroristas?. Análisis cualitativo del fenómeno InCel y discusión conceptual sobre el terrorismo”, Revista de Derecho Penal Y Criminología, 3.ª Época, n.º 24, pp. 193-244, 2020.

7 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, p.9, 2020.

8 TYE, Charlie, “Inside the warped world of incel extremists”. The Conversation, 16.08.2021, disponible en: https://theconversation.com/inside-the-warped-world-of-incel-extremists-166142

9 GANESH, Barath, “What the Red Pill Means for Radicals”, Fair Observer, 2018, disponible en: https://www.fairobserver.com/world-news/incels-alt-right-manosphere-extremism-radicalism-news-51421/.

10 BLOMMAERT, Jan, “Online-offline modes of identity and community: Elliot Rodger’s twisted world of masculine victimhood”, Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, Tilburg University, 2017, disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321532864_Paper_Online-offline_modes_of_identity_and_community_Elliot_Rodger%27s_twisted_world_of_masculine_victimhood.

11 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, Vol. 7, Issue 2, pp. 240 – 268, 2019.

12 Imagen 1. Adaptación de Stephane J. Baele et al.: Baele, J. Brace, L. y Coan, T. (2019): From “Incel” to “Saint”: Analyzing the violent worldview behind the 2018 Toronto attack, Terrorism and Political Violence.

13 KELLY, Casey y AUNSPACH, Chase, “Incels, Compulsory Sexuality, and Fascist Masculinity. Feminist Formations”, Vol. 32, Nº 3, pp. 145-172, 2020.

14 “Incels (Involuntary celibates)”, Anti-Defamation League, (s.n), disponible en: https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/incels-involuntary-celibates.

15 Imagen 2. BIBIPI. (2019). Hypergamy. InCels Wiki Est. 2018. Recuperado en: https://incels.wiki/w/Hypergamy.

16 KELLY, Megan, DIBRANCO, Alex y DECOOK, Julia “Misogynist Incels and Male Supremacism”, New America, p. 21, 2021.

17 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, op. cit., p.11.

18 KUEHL, Franziska, “Incel Communities: Breeding Ground for Radicalized Violence?”, Women in International Security, 2020, disponible en: https://www.wiisglobal.org/incel-communities-breeding-ground-for-radicalized-violence/.

19 TORRES-MARÍN, Jorge, NAVARRO-CARRILLO, Ginés, DONO, Marcos y TRUJILLO, Humberto Manuel, “Radicalización ideológico-política y terrorismo: un enfoque psicosocial”, Escritos de Psicología. Vol. 10, nº 2, pp. 134-146, 2017.

20 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, op. cit., p.3.

21 LABBAF, Farshad, “United by Rage, Self-Loathing, and Male Supremacy: The Rise of the Incel Community”, op. cit., p.22.

22 OREHEK, Edward y WEAVERLING, Casey, “On the Nature of Objectification: Implications of Considering People as Means to Goals”, Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 12, nº 5, pp. 719 -730, 2017.

23 LIGGETT O’MALLEY, Roberta. HOLT, Karen y HOLT, Thomas, “An Exploration of the Involuntary Celibate (Incel) Subculture Online”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, pp.1–28, 2020.

24 “When Women are the Enemy: The Intersection of Misogyny and White Supremacy”, Anti-Defamation League, (s.d), disponible en: https://www.adl.org/resources/reports/when-women-are-the-enemy-the-intersection-of-misogyny-and-white-supremacy#introduction.

25 KALISH, Rachel y KIMMEL, Michael, “Suicide by Mass Murder: Masculinity, Aggrieved Entitlement, and Rampage School Shootings”, Health Sociology Review, Vol.19, nº 4, pp. 451-464, 2010.

26 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, op. cit., p.13.

27 BINNING, Clare, “The undatables: inceldom, entitlement and the state-mandated girlfriend”, Gendering 2020(+1), Universidad de Glasgow, 2021.

28 Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), “Violent Incels and Challenges for P/CVE”, Comisión Europea, 2020, disponible en: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/orphan-pages/page/ran-small-scale-meeting-violent-incels-and-challenges-pcve-online-meeting-25_en.

29 MANAVIS, Sarah, “What is shitposting? And why does it matter that the BBC got it wrong”, New Statesman, 8.11.2019, disponible en: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/media/2019/11/what-is-shitposting-and-why-does-it-matter-bbc-brexitcast-laura-kuenssberg-got-it-wrong.

30 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, op. cit., p.13.

31 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, op. cit., p.14.

32 Dangerous Speech, “A practical guide”, Dangerous Speech Project, 2021, disponible en: https://dangerousspeech.org/guide/.

33 KUEHL, Franziska, “Incel Communities: Breeding Ground for Radicalized Violence?”, op. cit.

34 G2geek, “Stochastic Terrorism: Triggering the shooters”, Daily Kos, 11.01.2011, disponible en: https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2011/1/10/934890/-Stochastic-Terrorism:-Triggering-the-shooters.

35 HARPER MERCER, Christopher, “My Manifesto”, 2015, disponible en: https://schoolshooters.info/chris-harper-mercers-manifesto.

36 BEN AM, Ari y Weimann, Gabriel, “Fabricated Martyrs: The Warrior-Saint Icons of Far-Right Terrorism”, Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 14, nº 5, pp. 130 – 147, 2020.

37 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, op. cit., p. 8.

38 SIMONPILLAI, Radheyan, “Charging incels with terrorism won’t protect sex workers”, NOW, 28.05.2020, disponible en: https://nowtoronto.com/news/incels-terrorism-sex-workers-decriminilization.

39 JANIK, Rachel, “"I laugh at the death of normies": How incels are celebrating the Toronto mass killing”, Southern Poverty Law Center, 24.04.2018, disponible en: https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2018/04/24/i-laugh-death-normies-how-incels-are-celebrating-toronto-mass-killing.

40 SIMONPILLAI, Radheyan, “Charging incels with terrorism won’t protect sex workers”, op. cit.

41 TAISTO, Witt, “‘If i cannot have it, i will do everything i can to destroy it.' the canonization of Elliot Rodger: ‘Incel’ masculinities, secular sainthood, and justifications of ideological violence”, Social Identities, 2020.

42 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, op. cit., p. 20.

43 CHARLES, Angus, “Swallowing the Black Pill: A Qualitative Exploration of Incel Antifeminism within Digital Society”. Tesis de Máster, Universidad Victoria de Wellington, p. 73, 2020, disponible en: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/8915.

44 LEWIS, Jon y WARE, Jacob, “Spring Provides Timely Reminder of Incel Violence—And Clarifies How to Respond”, International Centre for Counter-terrorism, 2020, disponible en: https://icct.nl/publication/spring-provides-timely-reminder-of-incel-violence/.

45 LIM, Preston, “Canadian Authorities Charge Teenager With Terrorism Over Incel-Based Violence”, Lawfare, 30.06.2020, disponible en: https://www.lawfareblog.com/canadian-authorities-charge-teenager-terrorism-over-incel-based-violence.

46 LING, Justin, “Incels Are Radicalized and Dangerous. But Are They Terrorists?”, Foreign Policy, 02.06.2020, disponible en: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/02/incels-toronto-attack-terrorism-ideological-violence/.

47 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, op. cit., p.4.

48 TOMKINSON, Sian, HARPER, Tauel y ATTWELL, Katie, “Confronting Incel: exploring possible policy responses to misogynistic violent extremism”, Australian Journal of Political Science, p. 4, 2020.

49 “Incels (Involuntary celibates)”, Anti-Defamation League, op. cit.

50 HOFFMAN, Bruce, WARE, Jacob y SHAPIRO, Ezra, “Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence”, op. cit., p. 7.

51 JAKI, Sylvia, DE SMEDT, Tom, GWÓŹDŹ, Maja, PANCHAL, Rudresh, “Online hatred of women in the Incels.me forum Linguistic analysis and automatic detection”, op. cit., p.6.

52 ISLA JOULAIN, Gabriel Luis, “Célibes Involuntarios: ¿Terroristas?. Análisis cualitativo del fenómeno InCel y discusión conceptual sobre el terrorismo”, op. cit., p. 205.

53 SCOTT, Elfy y col, “How the alleged murder of a blogger has revealed the dark reality of ‘Incels’”, The Feed, 17.07.2019, disponible en: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/how-the-alleged-murder-of-a-blogger-has-revealed-the-dark-reality-of-incels.

54 SIMONPILLAI, Radheyan, “Charging incels with terrorism won’t protect sex workers”, op. cit.

55 No identificado por petición del juzgado en base a la Ley de justicia penal juvenil. El responsable era menor de edad.

56 LEWIS, Jon y WARE, Jacob, “Spring Provides Timely Reminder of Incel Violence—And Clarifies How to Respond”, International Centre for Counter-terrorism, 2020, disponible en: https://icct.nl/publication/spring-provides-timely-reminder-of-incel-violence/.

57 The United States Department of Justice. Office of Public Affairs, “Ohio Man Charged with Hate Crime Related to Plot to Conduct Mass Shooting of Women, Illegal Possession of Machine Gun”, 21.07.2021, disponible en: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/ohio-man-charged-hate-crime-related-plot-conduct-mass-shooting-women-illegal-possession.

58 GRIFFIN, Jonathan, “Plymouth shooting: Inside the dark world of 'incels'”. BBC News, 13.08.2021, disponible en: https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2021/aug/19/plymouth-attack-misogynist-incel-culture-podcast.

59 Tabla 1. Cronología de la violencia InCel (2009 – 2021). Fuente propia.

60 Sentencia del Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Ontario, 1258, CR-18-400000612-0000, 03.03.2021.

61 BRANSON-POTTS, Hailey y WINTON, Richard, “Cómo Elliot Rodger pasó de ser un asesino de masas a ‘un santo’ para los misóginos, entre ellos el sospechoso del ataque en Toronto”, Los Angeles Times, 26.04.2018, disponible en: https://www.latimes.com/espanol/internacional/la-es-como-elliot-rodger-paso-de-ser-un-inadaptado-asesino-de-masas-a-un-santo-para-un-grupo-de-misoginos-20180426-story.html.

62 Sentencia del Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Ontario, 1258, CR-18-400000612-0000, op. cit., p. 51.

63 Global Terrorism Database, “Incident Summary for GTDID: 201804230012”, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, disponible en: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/IncidentSummary.aspx?gtdid=201804230012.

64 JOHNSTON, Janice, “Frustration over involuntary celibacy led to killing, former security guard claims”, CBC, 28.08.2018, disponible en: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/edmonton-involuntary-celibacy-sheldon-bentley-manslaughter-jail-1.4803943.

65 RODGER, Elliot, “My Twisted World. The Story of Elliot Rodger”, 2014, disponible en: https://www.thenation.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/rodger-manifesto2.pdf.

66 Ídem.

67 NAGLE, Angela, “The New Man of 4chan”, The Baffler, nº 30, 2016, disponible en: https://thebaffler.com/salvos/new-man-4chan-nagle.

68 BRATRICH, Jack y BANET-WEISER, Sarah, “From Pick-Up Artists to Incels: Con(fidence) Games” Networked Misogyny, and the Failure of Neoliberalism”, International Journal of Communication, Vol. 13, pp. 5003-5027, 2019.

69 KELLY, Megan, DIBRANCO, Alex y DECOOK, Julia, “Misogynist Incels and Male Supremacism”, op. cit., p. 25.

70 Department of Public Safety, “Texas Domestic Terrosim Threat Assessment”, 2020, disponible en: https://www.dps.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/director_staff/media_and_communications/2020/txterrorthreatassessment.pdf.

71 ESTEVE, Joan, “Extremisme violent dins la Manosfera: La ideologia Incel i la seva presència a fòrums espanyols”, Tesis de Máster, Universidad de Barcelona, 2020.