The South China Sea, beyond Taiwan

The Indo-Pacific region is one of the main hotspots of tension in the world today. However, the problem goes far beyond the dispute between the People's Republic of China and Taiwan.

The South China Sea is increasingly emerging as the hottest area in a region where countries with interests in the region can clash.

Tensions in this space have been rising over the militarisation of islands, claims to fishing rights and conflicting interpretations of international maritime law, notably the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The region is a paradigm of the delicate balance between cooperation and competition, with various regional and non-regional stakeholders engaged in diplomatic posturing, military exercises and multilateral manoeuvres. This delicate interplay of powers, with a growing development of national interest, has put many countries in the position of facing what is known as "realpolitik".

China is staking a claim to almost ninety per cent of the sea's surface area, which is provoking territorial disputes with Southeast Asian littoral states and heightening tensions with the United States, its regional rival in power and itself an ally of several countries involved in these disputes. Over the past ten years, China has created several artificial islands in the South China Sea and turned them into military bases. With Beijing's increasingly aggressive attitude towards ships and aircraft of other states sailing or flying in the disputed areas, the risk of a miscalculation leading to an escalation into a military confrontation is becoming more and more likely.

Likewise, the South China Sea is also closely linked to the Taiwan issue for obvious reasons, for if China were to take the military option to occupy the island, the entire Southwest Pacific maritime area would become the theatre of operations for a war with unpredictable consequences.

The world economy today rides the waves of the sea. In a globalised world where economic interdependence creates the real links, control of the sea is the factor that determines control of the world economy. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in its 2015 update, estimated that eighty per cent of world trade by volume moves by sea and, of this, sixty per cent flows through Asia alone, with East and Southeast Asia acting as the world's main markets and producers. This means that one-third of this global trade takes place mainly in the South China Sea.

This explains in large part the developments we are witnessing in the region and why economies such as Korea, Taiwan, China, Japan and the ASEAN nations, for which the Strait of Malacca is a real bottleneck, are deeply concerned and involved in the South China Sea talks. This strait is the gateway to the Indian and Pacific Oceans, making it vital for all countries aspiring to economic growth and sometimes economic hegemony. This is where one can begin to realise the context of the relentless and pervasive US and Chinese efforts in and around this area.

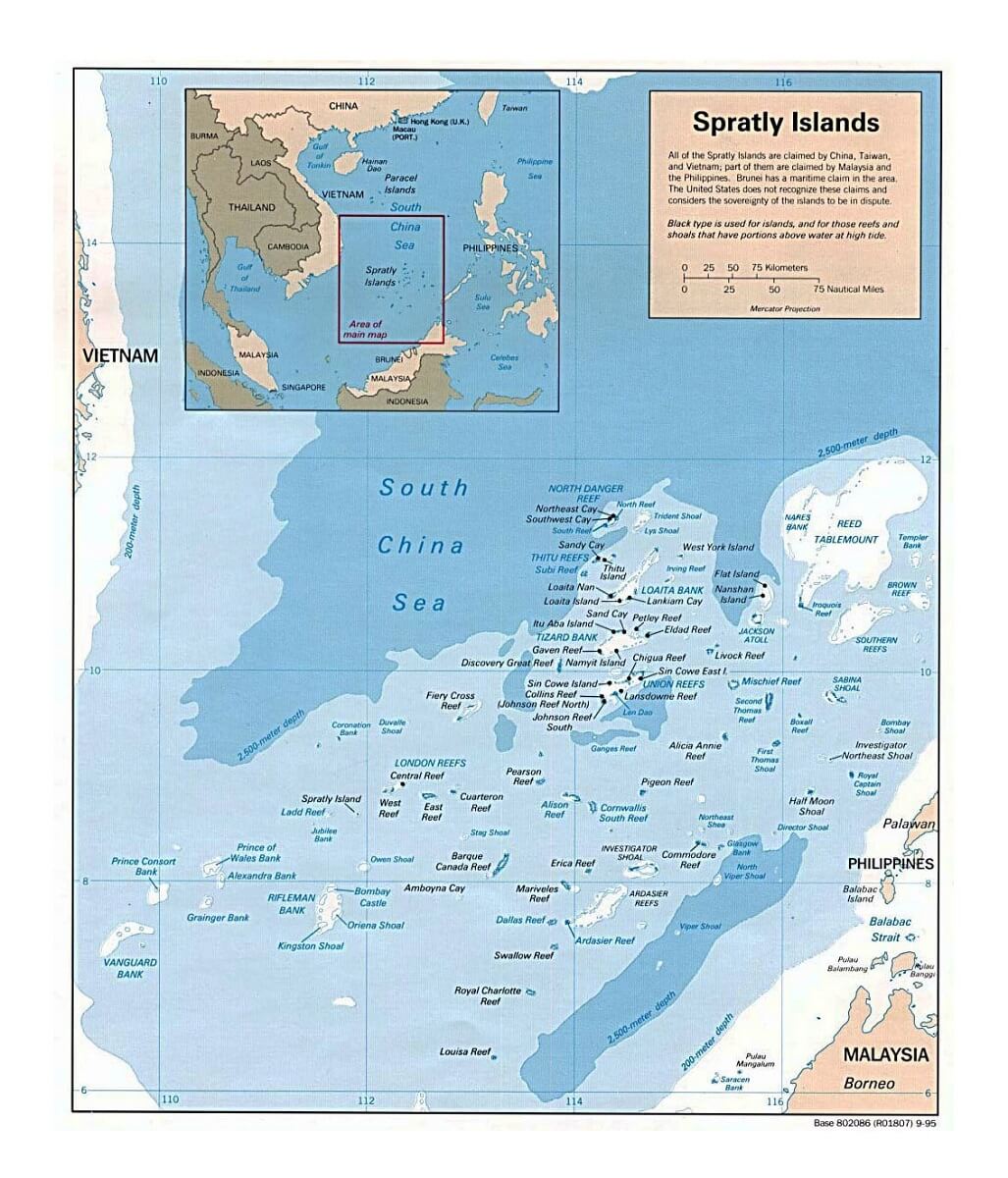

The strategic importance of the South China Sea (hereafter, SCS) is unquestionable. In line with what has already been mentioned, it should be made explicit that also almost a third of the world's seaborne crude oil exports pass through the SCS. Similarly, the most important maritime routes for the transport of goods and raw materials from Europe and Africa to Asia and vice versa pass through this area. The fisheries are very important, and the seabed is home to huge untapped oil and gas deposits. This last point alone can explain the enormous interest in controlling the region and gaining exploitation rights over these waters. This is why reefs and atolls that dot the SCS are claimed not only by China, but also by Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines and Taiwan, with the aggravating factor that their respective exclusive economic zones partially or totally overlap, something that does not help to reduce tensions.

It is not only geo-strategic considerations that are causing tensions to escalate in the ECM. Under Jiang Zemin at the turn of the millennium, the predecessor of current Chinese leader Xi Jinping set the goal of making China a 'maritime superpower'. From a geopolitical point of view, this measure, whose development continues to this day, could not make more sense. And what we might call, to emulate Robert D. Kaplan, "the tyranny of geography", supports this assertion. A simple glance at land borders, their orography and climatology is all it takes. Land communications are more than complicated, especially when it comes to the immense flow, both incoming and outgoing, of goods of all kinds that a country like China needs. That fact alone justifies why Beijing has turned its attention to the sea. In addition, China's economy, which since Zemin's time has evolved dramatically, transforming the country into what is sometimes called "the world's factory" (something Europe should rethink or at least think about), is absolutely dependent on maritime transport routes. This fact obliges the country, on the one hand, to have the means to secure those routes and guarantee incoming and outgoing maritime traffic, and, on the other hand, to have the capacity to protect, sustain and maintain the means of maritime transport throughout their journey.

This need can be described as vital or existential, as it is not only an economic issue. According to the FAO, only twelve percent of China's land can be considered arable. For a nation of more than 900 million people, this is a major problem, since something as basic as feeding the population depends on imports and thus on keeping the aforementioned sea routes open. Likewise, China's huge industrial complex needs huge amounts of energy resources to keep up with production, and this means that new sources of resources must be sought outside its borders, or that these must be expanded in order to gain access to new deposits.

It is this last point that can be seen as the main point of friction between China and the nations of the region and which, despite the focus on Taiwan, could actually provoke an armed clash.

As part of its policy, and as other nations do, China tries to interpret international law and the different conventions and treaties based on the law of the sea to its own advantage, trying to get the most out of them, but this line of action, which is totally legitimate, is added to the fact that since the middle of the last decade the Chinese government has been somewhat more expeditious in its actions on the ground, or rather, on the sea, trying to extend its control over the disputed waters, with a policy of fait accompli, using ships belonging to its coastguard service. This is interesting, as it shows a progression in the escalation in which it is attempting, for the time being, not to involve PLA forces.

Another step taken by China was its withdrawal from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, thus turning its back on the forum where the procedures for settling disputes between nations are established when their interests are in conflict. This step was taken at the same time as it began prospecting for energy resources in the disputed waters, in line with the policy outlined above.

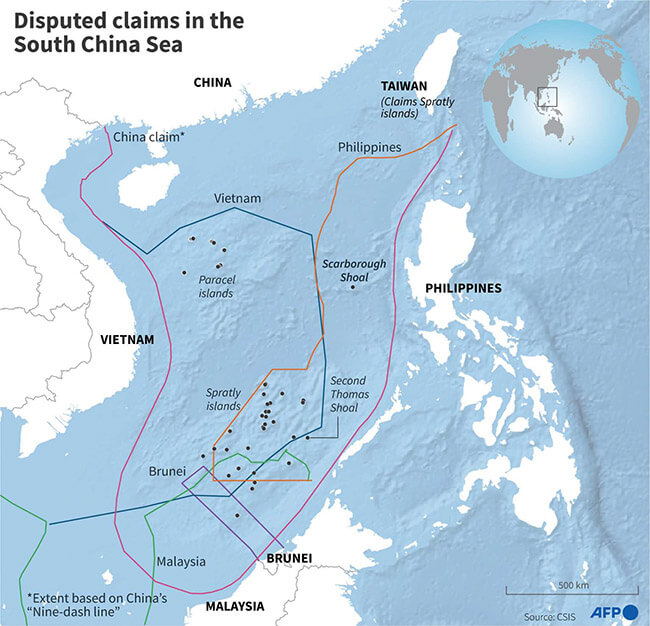

China claims sovereignty over ninety percent of the SCS, extending its claims to the coastal areas of the littoral states and including ownership of all reefs, sandbanks and natural resources in this area.

It was in 2012 that China began to build artificial islands on the rocks, reefs and small atolls, and then to expand them and establish military infrastructure on them. Obviously, the rest of the countries in the region have shown their concern, not only because of the threat this poses, but also because China is de facto appropriating areas that they claim for themselves, and is expelling them from areas that they have been using economically for decades or centuries in some cases.

The US attitude at a time when its focus of interest was elsewhere on the planet was then rather blasé and passive, but this all changed when China began to significantly expand its military presence and facilities on three of the new artificial islands. This led the US to increase its military presence in the region, conducting strategic patrols and participating in exercises alongside other countries' armed forces in the SCS. The aim was to demonstrate its position against China's territorial claims and its commitment to maintaining freedom of navigation.

But what are the main areas of dispute and tension? The most significant are the Paracel Islands (claimed by China, Vietnam and Taiwan) and the Spratley Islands (claimed by Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Brunei, Taiwan and the Philippines).

Around these two areas, China has established a myriad of positions that, if necessary, could deny navigation at a point that, in addition to harbouring important deposits, is a bottleneck for the flow of maritime traffic.

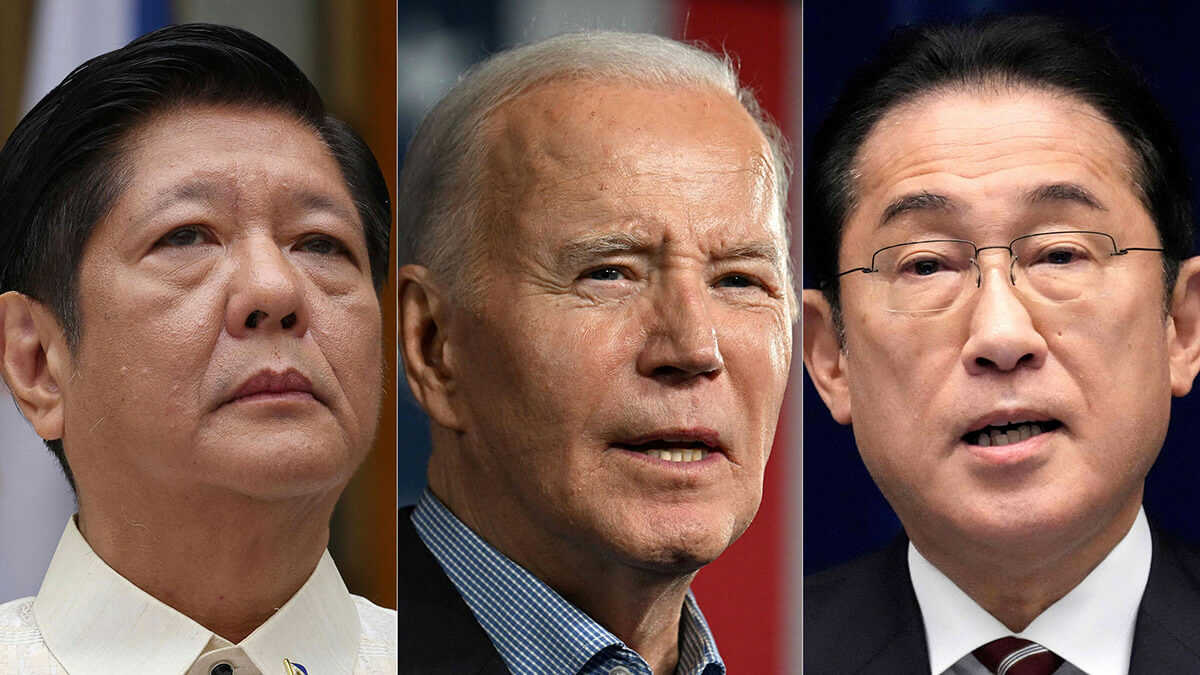

The clearest example of the consequences of Beijing's actions can be seen in the recent clashes with Philippine ships in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal Atoll, occupied since 2012 and for which the Philippines has filed a claim before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

Another actor that cannot be forgotten is India, whose presence in the South China Sea has also increased in the last decade. For New Delhi it is not just about the resources and exploitations of this expanse of sea, but its presence in the area is part of a much broader strategy to counter the Chinese dragon's expansionist ambitions. India has been pushing for its surrounding waters to be free of disputes, and sees its northern neighbour as a potential problem in the Indian Ocean, especially since the beginning of the development of what is known as the "String of Pearls", various bases, ports and facilities under Chinese control that mark the "New Silk Road". China's naval presence is undoubtedly a cause of concern for India. This goal of keeping trade and waters inclusive, open and legally protected is not unique to India, but is the concern of most ASEAN nations. India is trying to embrace the role of a more global power, being a case study of economic and national growth. This leads it to understand the importance of showing its presence but, at the same time, avoiding direct confrontational motives with China. A more pragmatic approach would be not to meddle in the complex geopolitical scene of Southeast Asia, but also not to refrain from honing new alliances under the 2014 Policy on Engagement in the East. India's contribution need not necessarily be entirely militaristic, but could adopt a more people-centred approach.

The South China Sea today represents all the symptoms of an area prone to a dangerous escalation of tension: attempts to balance different hegemonies, the race to exploit all kinds of resources to the maximum, collective security alliances, displays of power, and attempts at bilateral and multilateral talks to resolve problems.

But one thing that sets this region apart from most conflicts is its potential for an eventual local conflict to serve as a catalyst that pushes all the dominoes, involving all the powers with interests in the area and triggering a major war on a near-global scale or whose consequences would seriously affect the entire planet. At this point it is interesting to recall the words of Steve Bannon, chief White House strategist during Trump's tenure, who called the South China Sea the "New Middle East", noting that the next big war would be fought in a decade in the same region.

Countries such as India and the Philippines, as a result of China's keen interest in developing a naval force that can match that of the US in the future (although this is still far from being achieved), have already taken steps to adjust and improve their naval forces, acquiring new systems and making progress in establishing indigenous defence production capabilities. Improving maritime presence is increasingly important, considering that in the medium term China's naval supremacy over the SCS may be difficult to match.

The main challenge today is to find ways to de-escalate the tension. The Cold War formula of establishing direct channels of communication was once quite effective. This could reduce the current tensions between the naval and coast guard forces of the various actors. They all have unique dynamics and bringing them all to the same table to create a diplomatic space is a far-fetched idea and difficult to achieve. However, if done, some fruitful discourse could be glimpsed to help find a way out of a potential conflict by establishing confidence-building measures.

In conclusion, China's aggressive and fait accompli posture in the SCS needs a long-term vision and a combination of diplomatic, legal and military deterrence measures. But great care must be taken, as the wrong measures could deteriorate the situation and provoke an unprecedented Chinese reaction. It must be understood that the SCS issue is not just a regional conflict. Timely containment and resolution of this space will help extinguish before it starts a crisis that the world will have to face in the future. Close coordination between the parties concerned will reduce the chances of extra-regional interference and assist in a timely dissolution.

The solution will have to be global and inclusive, from Chinese aggression to Western alliance-building. All actors will have to be considered in order to craft a solution that leaves no one behind.