An ultrasound test at the end of pregnancy detects at-risk babies and avoids serious complications

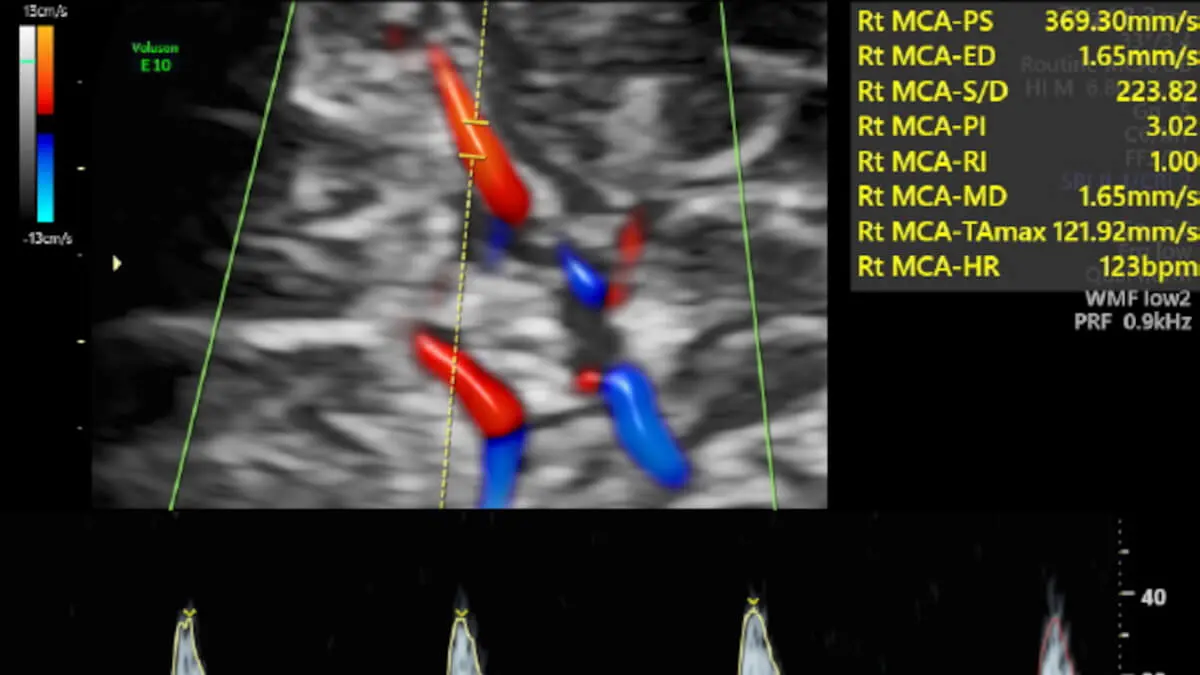

Determining the flow of the vessels of the foetal brain and placenta by means of Doppler in the routine ultrasound scan of the third trimester makes it possible to detect babies at risk of presenting postpartum complications that require admission to the ICU. Inducing delivery at term in such at-risk cases could halve the rate of admission to the neonatal ICU. This is demonstrated by an international multicentre study called RATIO37 published in the journal The Lancet.

- Background and rationale for the study

- RATIO37 international multicentre study: improving the detection of the risk of placental insufficiency

The study, in which several international centres have participated, has been conceived and directed by Francesc Figueras, head of the Fetal Medicine Service at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (IDIBAPS), and Eduard Gratacós, director of BCNatal (from Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona, IDIBAPS and IRSJD). The first signatory of the study is Marta Rial Crestelo, from the Fetal and Perinatal Medicine group (IDIBAPS and CIBERER).

Background and rationale for the study

Less than 1% of babies in low-risk pregnancies present in the last 2-3 weeks of pregnancy or at birth with a complication requiring admission to the NICU. Serious complications in babies in normal pregnancies are very rare, but when they occur they are very traumatic for the families.

A very frequent cause within that 1% is that the placenta no longer functions as well at the end of pregnancy. This is known as placental insufficiency and can lead to problems of lack of oxygen to the baby when contractions of the uterus occur at the end of pregnancy and during delivery. Detecting cases of placental insufficiency risk is key because it is possible to end the pregnancy at term (37 weeks) and greatly reduce or even avoid serious complications.

Until now, the detection of this risk has been based on performing an ultrasound scan at the end of the third trimester to identify babies with low birth weight, a circumstance that is often caused by placental insufficiency. However, this method does not detect all at-risk cases. Some normal-weight babies also have placental insufficiency, which, however, because of its late onset, has not led to reduced foetal growth.

A Doppler ultrasound test that measures blood flow through the umbilical cord and brain, called a brain-to-placental ratio (or CPR), can detect placental insufficiency. Until now, this test was only performed in problem pregnancies, in highly indicated cases. For more than 10 years there has been a debate in the scientific world about whether CPR should be measured in all pregnant women or whether it is an unnecessary waste of resources. If Doppler testing were to be carried out in all pregnancies, it might improve the detection of babies at risk of complications from placental insufficiency. But there would also be a risk that the test would not improve anything and, instead, would only generate more expense and distress for mothers.

The RATIO37 study was supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation, the CEREBRA Foundation and the hospitals Clínic and Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona, and its aim was to assess precisely this question: could we improve the identification of babies at risk and reduce serious neonatal complications by measuring CPR in all pregnancies?

The research team led by Dr Francesc Figueras and Dr Eduard Gratacós considered the possibility of extending the study of placental function with CPR to the third trimester ultrasound of all foetuses, regardless of the estimated foetal weight. "We thought that studying placental function only in low-weight foetuses limited the detection of placental insufficiency and that by extending this study to the entire population we could improve the detection of those babies at risk of requiring admission to the ICU and prevent it by inducing labour at term", explains Dr Figueras.

RATIO37 international multicentre study: improving the detection of the risk of placental insufficiency

The RATIO37 study involved more than 11,500 women with low-risk pregnancies over six years. At the 36-week ultrasound scan, CPR was measured in all women, but the participants were randomly divided into two groups. In one group, the test was used to change the management of the pregnancy and, if the result was abnormal, the woman was offered early induction of labour at term. In the others, the test result was not reported and the pregnancy was managed according to current protocols. The study compared the numbers of cases of infant death and severe neonatal complications (including neurological, intestinal, cardiac, renal, cardiac, respiratory and other neurological problems, with an ICU stay of 10 days or more) that occurred in each group.

The results showed that severe neonatal complications occurred in 0.38% of pregnancies in which CPR was used and in 0.73% of pregnancies in which CPR was not used. It took a study as large as this one to be able to demonstrate a seemingly small difference, but one that represents a reduction of 3.5 cases of serious complications per 1,000 pregnancies classified as "low risk". If these figures are extrapolated to the total number of births in Spain in 2022 (330,000), 1,150 serious neonatal complications could be avoided.

"The study has shown for the first time that, by adding the CPR study to all foetuses in the third trimester ultrasound, it was possible to detect those babies at risk of presenting complications and requiring admission to the ICU, regardless of their birth weight. Induction of labour in foetuses showing signs of placental insufficiency halved the number of complications requiring admission to the ICU," explains Dr Rial.

"The results are very relevant, they provide data that will be fundamental in a scientific debate that will last more than 10 years and represent an advance in the development of better ways to refine the detection of at-risk pregnancies and prevent serious neonatal complications. Over the next few years, these results will generate debates in societies and congresses. How they are applied in each setting will need to be assessed. But they will undoubtedly lead to changes in the recommendations of many of the professional guidelines on pregnancy control around the world," explains Dr Gratacós.

An additional benefit of the study is that it advances the goal of being very strict in the selection of cases that benefit from induction of labour. Some scientific societies and international professionals support the option of induction of labour at term in nulliparous pregnant women (who have not had previous deliveries), because it has been shown to reduce severe neonatal complications and does not worsen the rate of caesarean sections. However, this would result in half of the pregnant women having to go into labour. This study demonstrates that it is possible to identify much more selectively, namely 5%, of pregnancies that really benefit from a measure such as induction of labour, and this represents a step towards personalised, minimal intervention maternal-fetal medicine.

The study was carried out in 6 different countries and involved the following collaborating centres and international leaders: Palacky University, Olomouc, Czech Republic (Marek Lubusky); Institute for Women's and Children's Care, Prague, Czech Republic (Ladislav Krofta); University Hospital in Hradec, Kralove, Czech Republic (Marian Kacerovsky); St. Sophia Hospital, Warsaw, Poland (Anna Kajdy); Soursaky Medical Centre, Tel Aviv, Israel (Eyal Zohav); Hospital Universitario de Santiago de Chile (Mauro Parra Cordero); Hospital de Mar, Barcelona (Elena Ferriols Pérez) and Hospital de Especialidades del Niño y la Mujer, Querétaro, Mexico (Rogelio Cruz).