Refugees: what's really happening on the Turkish border

Chronichle from Pazarkule-Kastanies (Turkey), border checkpoint with Greece

There's smoke. A lot of smoke. Hundreds of bonfires crackling and sizzling in the camp that has sprung up on the stretch between Greece and Turkey. Breathing in that atmosphere has become almost a challenge, for the smoke carries only scorched air into the lungs. Every breath brings with it an inescapable feeling of burning and an incessant urge to cough. And all around, a multitude of eyes are watching wearily. There are more than 3,000 people spread out on the esplanade in front of the Pazarkule-Kastanies border post, where the Greek authorities have improvised a wire fence to prevent access.

Thus, the shock wave that has been generated after the attacks in the Syrian province of Idlib last Thursday night, has brought about a massive mobilization throughout the Eurasian country. The Erdogan government implicitly stated that it would not hinder those who wanted to cross over to Europe: “Our policy on refugees is the same as always, but the situation is what it is. We are not in a position to stop the refugees now”, said AKP spokesman Ömer Çelik. With this sentence, the echo of the constant presidential threats regarding migration management, come back like a boomerang. With the encouragement of the end of the 2016 anti-migration agreement signed with Brussels, the warning is fulfilled: “from now on, we will no longer close the border”, which had been repeated so often. Sayings have become deeds. After all, Turkey is already hosting more than 3.7 million refugees in its territory.

The ebullition behind these words has spread through Facebook, Twitter and so-called “word of mouth” in the streets, causing the news to spread like wildfire. Less than 24 hours after the Turkish army confronted Bachar al-Asad's forces, thousands of refugees were already moving swiftly to the area bordering Greece and Bulgaria. Some by taxi, others on foot; but the vast majority of those who have made it to the border have done so thanks to the buses which - unofficially - have been financed by Ankara.

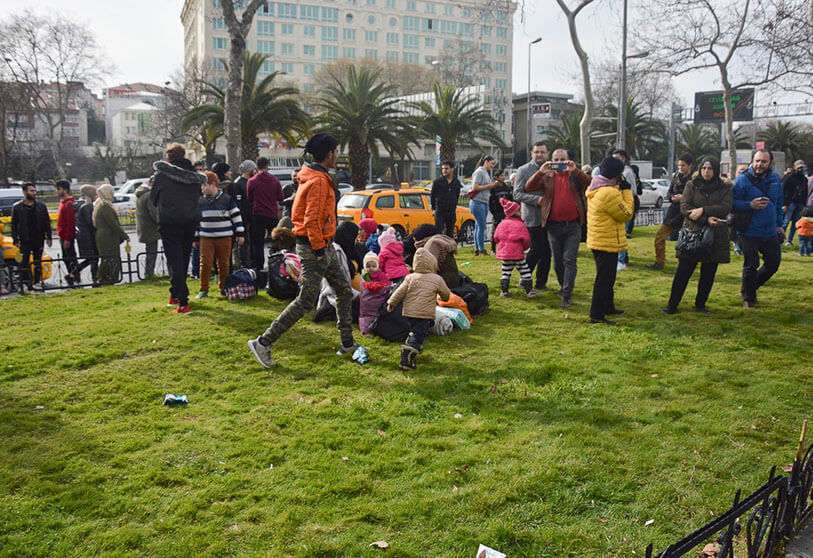

Thus, by early Friday morning, several districts of Istanbul were already chartering dozens of buses to transport Syrians, Afghans, Iranians and Somalis to the areas of interest. The faces in those places reflected joy, hope. Every time one of the cars left the meeting point, those still waiting their turn threw cheers into the air and from inside, several hands waved, waving insistently and conveying a very clear message: “We have a chance, we are finally going to be happy, we are finally going to rest”, as Isam, who had come all the way from Damascus, said.

The hopes raised by the Turkish Government, however, were quickly dashed into the void as soon as they knocked on the door of the European safeguard, which has closed its border completely. The joy has evaporated. They have all become puppets, dancing to the sound of the political game that the events in the de-escalation zone' have triggered. The President of Turkey has wanted to cover his flanks and is urging the European Union, through pressure on its border, to become actively involved in the humanitarian crisis.

Ahmed, a refugee from an area near the Euphrates, looks at the ground with resignation in the face of one of the many fires that have been lit: "We all thought we had a chance. A small one. But there it was. He looks up, revealing his eyes, red and irritated from the tear gas with which the Greek authorities have responded. All around him, families with young children lie on the plain, staring blankly. No laughter is heard. The gas, sound bombs and shots in the air have made it clear to them that they will not be able to cross over into Greece.

A large number of hands approach the flames, trying to find a slight sensation of heat, however slight. The bodies come together and hug, seeking comfort from each other, but without really interacting with the strangers. Fear for events is joined by fear for others. You hear arguments. Many of them try to rest in the open with their hoods pulled back. Their clothes are full of mud, as a result of the raging storm that occurred during the night. “There is nothing we can do but wait and pray”, Ahmed continues. He, like many of those present, has been living badly in Istanbul for several years, trying to survive as circumstances permitted: “I want to get to Germany and work there. It is my dream”.

After almost 24 hours of anxious waiting and resistance to the political and social situation, several trucks have set up near the “camp” area and have begun to distribute food and water. Long queues have formed of people whose feet were tapping the ground in excitement over the small spark of light this has brought. UNHCR and the Red Crescent have been the main promoters of this assignment, although some health care posts have also been set up, organized by the Turkish government.

Already on Sunday, many of the refugees who were resisting in Pazarkule and other points of the border, have left their post and decided to return to Istanbul. Others take advantage of the chaos in the Greek-Turkish area and continue with perseverance, looking for a weak point in the forces of the Greek Army to access what they wrongly called the “safe zone”.

The great avalanche of refugees trying to cross over to European soil has caught Bulgaria and Greece off guard, with the latter having generated the most commotion and having had to face the greatest flow of attempts to reach Greek territory. Both by land and by sea, thousands of people have left everything behind and are desperately seeking to find a glimmer of hope in their future prospects.

From Turkey's Mediterranean coast, in the province of Izmir, dozens of makeshift boats have precariously moved what has already become thousands of refugees this Sunday. Despite this, the official figures of the Greek Government show that only 66 people have entered illegally. A Coast Guard spokesman told EFE that "we are strengthening our defenses by land and sea, more police forces are being deployed in Evros and 52 Navy vessels are currently operating on the islands.

Meanwhile, on the land border to the north of the former Ottoman Empire, the response has been to use tear gas, sound bombs and shots in the air. From the Greek island of Lesbos, boats arriving on the coast have been destroyed and thousands of border guards have been equipped to prevent access to the country. Many witnesses and journalists in the area claimed that various racist groups had beaten up refugees and unofficial sources had shared videos of how one of the UNHCR centres, which served as an access point for new arrivals, had gone up in flames.

At the same time, the Moria refugee camp on the island is facing an even worse humanitarian crisis than it did before: despite having a capacity for 3,000 people, there are currently 21,000 living in the vicinity and with the arrival of the boats, even greater congestion is expected with totally insufficient supplies.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced on Sunday via his Twitter account that: “Our national security council has taken the decision to maximize the level of deterrence at our borders. From now on we will not accept any new asylum applications for one month. We invoke Article 78.3 of the TFEU to ensure full European support”.

Thus, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union states in the point quoted that: “If one or more Member States are faced with an emergency situation characterised by a sudden inflow of nationals of third countries, the Council, acting on a proposal from the Commission, may take provisional measures for the benefit of the Member States concerned. The Council shall act after consulting the European Parliament”. What can be inferred from this declaration and the achievement of the relevant article is that there is no intention of giving in to migratory pressure and that the measures to be used to deal with the crisis will be merely “provisional” and aimed at reducing the peak of the imbalance.