Berlusconi, Forza Italia and the future of the centre-right

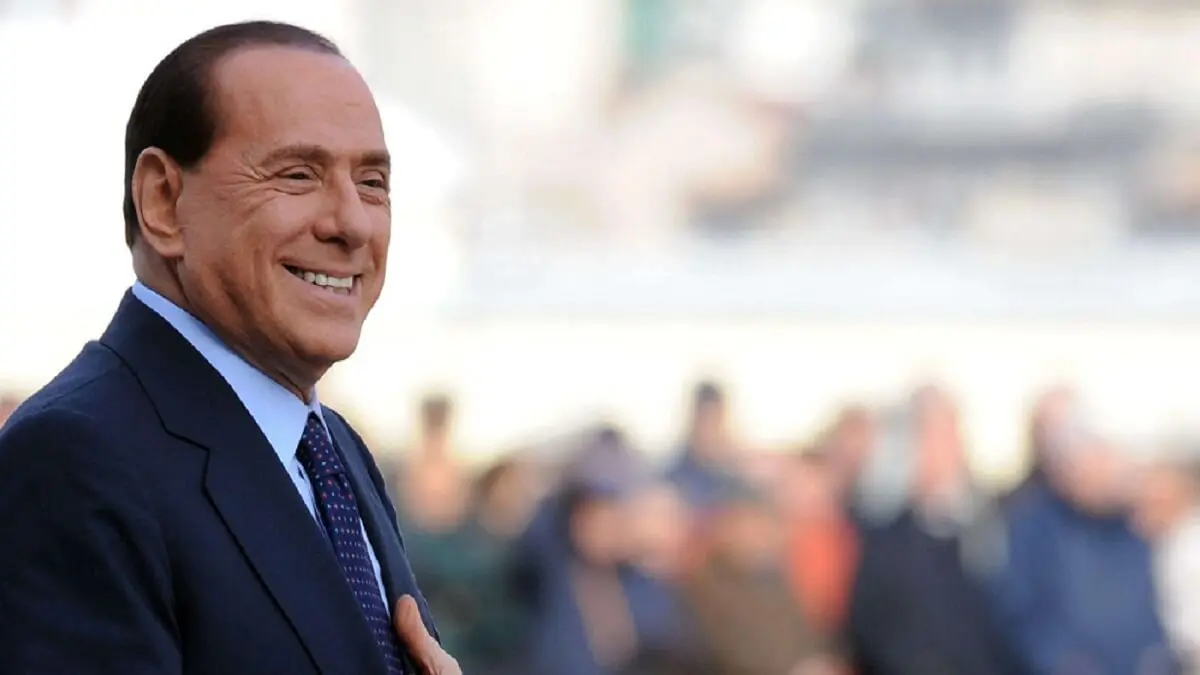

The death on Monday 12th of Silvio Berlusconi, four-time prime minister and the most influential man in Italian politics for the last three decades, leaves many questions that time will take care of resolving. It should be remembered that "Il Cavaliere" did not want to designate a successor: he did not do so in favour of one of his five sons; nor did he do so in favour of the main figures of the centre-right (the "premier" Meloni and his deputy prime minister Salvini); and the only thing he has limited himself to doing, mainly because of his advanced age, is to leave the party increasingly in the hands of the current deputy prime minister and foreign affairs minister (Antonio Tajani).

From the point of view of the governability of the country, where the Roman Meloni has chaired the Council of Ministers since 22 October, Berlusconi's death has not, in principle, altered the balance of power within the executive in any significant way: Having obtained only 8.1% of the vote in last September's elections, Forza Italia has no ministers in key portfolios such as Economy and Finance (in the hands of the "legista" Giorgetti), Justice (in the hands of the prestigious former judge Nordio, who was appointed by Meloni), Interior (in the hands of Matteo Piantedosi, a civil servant in this ministry who has been working on these issues since the late 1980s) and even Defence (whose head is Guido Crosetto, co-founder with Meloni of Fratelli d'Italia). So it is likely that Forza Italia will continue to support the Meloni government, given that in recent months it has moved from Euroscepticism to Europeanism.

Another issue is what will happen to Forza Italia itself. Because, with the death of "Il Cavaliere", who brought together all the elements around him, we now find that this party is now heavily in debt and that if it was still active it was because Berlusconi backed the party he himself founded in early 1994 with his personal wealth (valued at some 6 billion euros). It should be borne in mind that none of "Il Cavaliere's" children have not only not entered politics, but have not shown the slightest interest in taking over from their father: to date, it seems that the five offspring of the Lombard businessman and politician prefer to dedicate themselves to the business world, which was precisely what their father had dedicated himself to before entering politics: it remains to be seen whether his main heirs will want to continue putting money into a political party that remains to be seen whether it has a real future.

Antonio Tajani, MEP since 1994, president of this same House between January 2017 and June 2019 and now, as we have said, deputy prime minister and foreign minister, has already said that the party will remain active, and that he will personally assume its leadership. But it remains to be seen whether Berlusconi's voters see in Tajani his true successor, something that we will be able to see in the call for government elections in different regions in the coming months (Abruzzo, Molise, Sardinia, etc.). Tajani has the advantage that the party was at a low level of electoral support (basically, right now the polls give it between 7 and 7.5% of the vote), and, logically, in a person as little known as he is because he has spent most of his political career in the European institutions, he will have to multiply his presence in the media to make himself known to voters who in recent years have seen him a lot in the transalpine lands, but of whom they hardly know anything about him.

Assuming that Tajani is not even able to come close to the 8.1% achieved in last September's general elections, then it will not be surprising to see a steady flight of MPs from the party to other parties. Most can be expected to go with Meloni, who after all enjoys high levels of popularity at the moment and is managing to handle himself skilfully in both the national and international worlds. Another possibility is to join the party of Matteo Salvini, deputy prime minister and head of infrastructures, but Salvini has been in the doldrums for many months now and, moreover, his party has traditionally been very anti-European, while Forza Italia, let us remember, has for decades been part of the European People's Party (EPP), the majority party in the European Parliament.

There remains a third possibility that, in the end, would not surprise many: to go with Matteo Renzi and his party, Italia Viva. Renzi has spent most of his political career with the Democratic Party (PD), thanks to which he was able to be president of the Council of Ministers in February 2014 and December 2016 (its Executive has been the only one capable of surpassing 1,000 days of life along with two presided over by Silvio Berlusconi and one headed by Bettino Craxi), but in September 2019 he left the PD to found his own party, Italia Viva.

Renzi has maintained until the end a very good personal relationship with "Il Cavaliere", with whom he forged the famous "Pact of the Nazarene" between January 2014 and January 2015. He likes to recall that "I have never voted for Berlusconi, but I have never attacked him either", and, while he was in the PD, he went out of the line of harsh confrontation with Silvio Berlusconi: he said, not without reason, that Berlusconi "should not be liquidated, but retired". And the most important thing: Renzi is a classic Christian Democrat, who could not belong to the Christian Democrats (DC) because of his age (this historic party disappeared in January 1993, when Renzi had just turned 18), and he has never been a socialist nor has he been identified with the official line of the PD, a party which, by the way, Berlusconi disparagingly called "the formation of the catommunists".

Renzi knows that he has a good number of followers within Forza Italia, not least because the merciless attacks that "Il Cavaliere" suffered during his lifetime were also suffered personally by this Tuscan politician and now senator for Campania. But Renzi, as skilful as few others, knows that he still has to wait for developments: at the moment the "strong" person in transalpine politics is the Roman Meloni, so it is to be expected that for the moment the vote of those who supported Berlusconi will be divided between those who see Tajani as the natural successor to "Il Cavaliere" and those who consider, on the other hand, that the important thing is that the centre-right coalition does not lose strength and therefore decide to switch to Brothers of Italy (the party of the "premier" Meloni).

Another issue is what might happen in a year's time: more specifically, between 6 and 9 June, when the European elections will be held. Renzi has been working for months to create a strong coalition in which, on the one hand, what he calls "sovereigntists" (Meloni and Salvini) and, on the other, the "populists" (Democratic Party and Five Star Movement) are left out. In principle, the idea of Renzi, who is part of the "Renew Europe" group (led by the President of the French Republic, Emmanuelle Macron) is to try to win one of the leading positions in the European Union: either to be President of the Commission (as Romano Prodi was between 1999 and 2004), or to be appointed President of the European Council, where there has never been an Italian at the head (of the three that have been, Van Rompuy and Michel are Belgian, while Tusk is Polish).

But Renzi also knows that, by the time the European elections are held, Meloni will already have a significant level of attrition: growth of 0.9-1% is currently forecast for the eurozone as a whole; Italy will have a very large national debt (we do not yet know the figures for 2023, among other reasons because there is still half a year to go, but we do know that the national debt to GDP, in the case of Italy, was already 154% at the end of 2022); and this debt will also have to deal with the consequences of interest rate rises, which have just reached a maximum of 4%. If Matteo Renzi, in his own words, when he was "premier" had to pay some 77,000 million euros in interest on the debt when interest rates were between 0 and 0.5% and with a national debt/GDP of 132.6%, how much will Meloni have to pay in the General State Budget for 2024?

Added to all this is the recovery of the Stability and Growth Pact. The central and northern countries of the Union agreed to make their position more flexible, but they made sure that two fundamental points were not touched: a maximum of 60% debt as a percentage of national GDP and a 3% deficit target. From then on, the commitment of the most indebted economies (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and France, which has just been added to this group) was to gradually reduce this level of debt, which means that Meloni will have to give up many of his social policies, and that unrest may return to transalpine society: not enough to end in another catastrophic Five Star-Lega government, but enough to make Roman politics increasingly unpopular among the population and increasingly questioned among the political class. And, paradoxically, should the Meloni government fall before the end of the legislature, the presidency of the Council of Ministers could fall to Antonio Tajani: unlike Salvini, he has a university degree (no Italian prime minister has ever formed an executive without a university degree), and he is also highly regarded in EU circles, in contrast to Salvini, who has traditionally been the European Union's main enemy to beat.

The prestigious Italian public television journalist and presenter of the programme "Porta a Porta", Bruno Vespa, an institution in the country not only because his programme is a leader in audience figures, but also because he has been working for the public broadcaster for more than 54 years, said a few days ago: "Renzi is the political son that Berlusconi has never had". Same communication skills, same leadership skills, similar detractors, similar vision in many fields and extraordinary mental strength. Renzi's fundamental problem? He is seen as "unreliable" because of the swerves he has had no choice but to make in order to survive in politics. But he still enjoys the prurience of having been the youngest prime minister in the history of the republic, and he knows that, just as he cannot even be seen by most of the "catocommunists", he is much better perceived within the centre-right.

In any case, there is still a long way to go before we know what will happen with Forza Italia and the centre-right as a whole. For the moment, the vote has been divided between Renzi and Calenda's Terzo Polo (7.8 per cent of the vote in the September 2022 elections) and the aforementioned Forza Italia (8.1 per cent of the vote). But many know that, whoever leads this centre-right, it is actually worth much more in terms of number of voters: the 26% that Meloni won last September is much higher than his actual figure (remember that in the previous general elections, those of March 2018, only 4.4% of the electorate voted for him), because part of the voters of "Forza Italia" decided to change their vote to this Roman and centralist party. The reality is that now is the time for Tajani, as the "strong man" of what remains of the party founded by Silvio Berlusconi in early 1994; and for the aforementioned Meloni, who in all polls does not fall below 29% of voting intentions.

The truth is that the centre-right is living a moment of tremendous orphanhood: Renzi is too far to the left, Meloni is clearly right-wing and Tajani is an unknown quantity. But this centre-right enjoys a very broad electoral base: it is the one that guaranteed the Christian Democrats (DC) control of all governments between 1945 and 1992, and the one that did the same for Silvio Berlusconi in subsequent decades. The DC has not existed since January 1993, and now its successor ("Il Cavaliere") has just passed away. What will happen to this sort of "terzo polo" that not even Renzi has managed to cover for the time being? Time will tell, but the stakes are high because it is in this temperate zone of the ideological arc that the country's sociological majority is to be found. Now it is time to await events, waiting for the final outcome.

Pablo Martín de Santa Olalla Saludes is a lecturer in the Faculty of Communication and Humanities at the Camilo José Cela University (UCJC) and author of the book Historia de la Italia republicana (1946-2021) (Madrid, Sílex Ediciones, 2021).