Sergio Mattarella: a decade at the head of the Italian Republic

- Functions of the president

- Popular support

- The pact with Salvini

- The pandemic crisis

- Draghi to the rescue

- Mattarella's second term

- Meloni's rise

- Two and a half years of peace

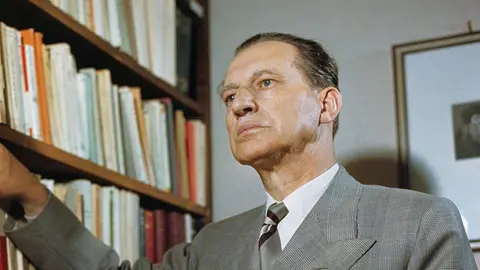

This 31st of January marks a decade since the Sicilian Sergio Mattarella first assumed the Presidency of the Italian Republic. Seven years later, at the end of January 2022, he was re-elected for a second term, as the 1948 Constitution does not include any term limits. This, by the way, has made him the head of state who has been the country's highest authority for the longest time, surpassing the ‘record’ of the previous president, the late Napolitano.

So it's time to take stock of what has been a very well-executed presidency by a man as austere as he is knowledgeable about his presidential duties. Because, let's not forget, Mattarella was for years a professor of Constitutional Law and the main mandate of every president of the Italian Republic is to uphold and enforce the Constitution.

Functions of the president

The election, term of office and functions of the President of the Republic are formally set out in articles 83 to 91 of the 1948 Constitution. But it should be added, because of its real importance, number 92, since this article addresses the figure of the president of the Council of Ministers (in other words, the ‘premier’ or prime minister) and the way in which the task of forming a government and designating the components of that particular executive is conferred. This gives us an initial key idea about the importance of being president of the Republic: respecting the existence of a ‘maggioranza’ to govern, the truth is that the candidate to receive the Presidency of the Council of Ministers must carry out the unofficial ‘pre-incarico’.

What does this ‘pre-incarico’ consist of? Basically, it consists of informing the Presidency of the Republic of the composition of the government and its members. In the event that the President of the Republic does not consider the candidate for ‘premier’ or the assignment of some ministerial portfolios to be suitable, he then makes this known to whoever wants to assume the presidency of the Council of Ministers, because the President of the Republic, in the event that he is not listened to, reserves the right to call new elections or to ‘incarico di governo’ another person.

Of course, this is a decision that must be taken with great caution. So much so that Mattarella has only exercised it on one occasion: when Matteo Salvini, leader of the League, tried to ‘slip in’ Paolo Savona, a well-known anti-single currency politician, as Minister of Economy and Finance (May 2018). Mattarella, without hesitation, not only refused, but also withdrew the mandate to form a government. Finally, this portfolio ended up in the hands of the ‘orthodox’ Giovanni Tria, professor of economics at the University of Tor Vergata, with Savona moving to the portfolio of European Affairs. It was then that the coalition government between Five Star and the League was born, with the famous ‘government contract’ as its objective.

Popular support

The reality is that, at the present time, Mattarella is more recognised than ever among the transalpine population, while Matteo Salvini, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Infrastructure since 22 October 2022, is wanted for liquidation in his party, taking into account that he has gone from having 33% support in 2019 to less than 10% at the moment.

What's more, his candidate for the presidency of the Umbria region, Donatella Tesei, lost the government in mid-November to an unknown candidate put forward by the centre-left.

In this sense, Mattarella's presidency, who has been head of state for three consecutive legislatures (2013-18, 2018-22, and from 2022 until now), has gone through three different phases. Chosen to preside over the Republic by the then young President of the Council of Ministers Matteo Renzi (both, by the way, Christian Democrats) at the end of January 2015, he had a very quiet Presidency until April-May 2018. He found himself with a very strong majority that gave Renzi almost two more years in government (February 2015-December 2016) and which was then picked up by the former Foreign Minister (Paolo Gentiloni, December 2016-May 2018).

The problems for Mattarella would come after the elections of 4 March 2018. The Five Star Movement, with 32.6% of the vote, had clearly won the national elections, but needed another party to reach a majority to govern. There were two possibilities on the table: the Democratic Party (PD), of which Mattarella had been a member of parliament in the 2006-08 legislature, and Salvini's League. Although the veteran Sicilian jurist and politician was inclined towards the PD (not only because he had many contacts there, but also because it belonged to the second most important family in the European Union, the socialists), the truth is that, without counting the defenestrated Renzi, only the PD leaders were in favour of negotiating, since Five Stars had cemented its electoral victory on the basis of a ruthless attack on this centre-left party, particularly targeting its leader, Matteo Renzi, and attacking his own family.

The pact with Salvini

So the only possibility left was to make a pact with Salvini's League, something that Mattarella did not like in the least because the League is strongly anti-European and Five Star was not exactly close to the community authorities either. Hence the need for no less than three months of negotiations.

Before entrusting them with forming a government, Mattarella made sure that Foreign Affairs went to Enzo Moavero Milanesi (a pro-European who had already been part of the Monti government) and that Economy and Finance went to the aforementioned Giovanni Tria. Despite this, the budget negotiations for 2019 were a constant headache for Mattarella, with Salvini unashamedly insulting the then President of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, whom he publicly accused of having alcohol problems.

But the truth is that both the leader of the Five Star Movement (the inexperienced Di Maio) and that of the League ended up ‘swimming and saving their clothes’ and there was a pact on the deficit for the 2019 General State Budget, which stood at 2.04%.

Mattarella would take his personal revenge on Salvini (let's remember the historical enmity between the ‘lawmakers’ and the Christian Democrats, which dates back to the end of the 80s, when Umberto Bossi, founder of the League, started out in politics). With the government having fallen in August 2019 and bearing in mind that sectors on the centre-left that were very much opposed to each other were going to unite because, if there had been elections, Salvini could have become prime minister, Mattarella forged a new ‘maggioranza’ in which there was Five Stars and, now, the PD. On this occasion, Renzi was not only not an obstacle to this, but also publicly showed his support, giving rise to a four-party coalition: Five Star, PD, Italia Viva, and Free and Equal.

The pandemic crisis

Just when calm had returned to transalpine politics, something completely unforeseen and with tremendous consequences appeared: the pandemic generated by the coronavirus, against which there was no vaccine at the time and which wreaked havoc on people with the most weakened organisms (especially the oldest populations). Mattarella knew how to act with his characteristic temperance and, in addition to fully supporting the Executive, he set an example by getting vaccinated like any other Roman citizen, in a photo that became famous.

At that time Italy, first Lombardy and some specific areas (such as Ancona and Pesaro) and then the whole of the national territory, had implemented strict rules of confinement of the population. The community authorities, aware that this meant a setback for most of the world's economies, had held a summit in July 2020 to launch the so-called ‘European Recovery Fund’, popularly known as the ‘new Marshall Plan’, in memory of the successful programme of reconstruction of the European continent financed by the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It had been decided to launch two types of transition: the digital and the environmental. And to this end, 750 billion euros had been allocated for the seven-year period 2021-27, of which Italy would be the main beneficiary: it would receive no less than 209 billion, followed by Spain with 140 billion.

But it soon became clear that the European Recovery Fund could not be implemented through public management alone: it quickly became necessary to turn to the private sector and, in particular, to consultancies. By that time, Renzi's relations with Five Star and the PD were deteriorating, as they wanted to marginalise him from the handling of European funds, thinking that the former prime minister would ‘swallow’ it. He didn't do it, abandoning the ‘maggioranza’ in January 2021 and leaving the remainder of the coalition government with a meagre parliamentary advantage, which had no choice but to submit to a vote of confidence.

They won it, but not before putting on an embarrassing display involving phone calls from all over the place, offers (Matteo Salvini claims, and credibly, that he was offered the Agriculture portfolio by three different people from his party, and at the same time) and even the chasing through the corridors of Parliament of senators of the lowest moral calibre, such as Lello Ciampolillo from Puglia, expelled from the Five Stars and at that moment in the Mixed Group.

Here again Mattarella brought out his strong character (well hidden by his very kind manner) and not only summarily dismissed the government, but immediately called on the best of the best: Mario Draghi, former director general of the Treasury, former governor of the Bank of Italy and former president of the European Central Bank (where he had become famous for saving the single currency after the resounding failure of the austerity policy imposed by Germany and its allies from the centre and north of the European Union).

After the Ciampi government (1993-94) and the Dini government (1995-96) set up by President Scalfaro, and the Monti government (2011-13) promoted by President Napolitano, a new government of independents was ‘brought to life’. And the veteran and prestigious RAI journalist Bruno Vespa's statement was fulfilled: ‘when politics fails, the figure of the President of the Republic emerges’.

Draghi to the rescue

Mario Draghi said ‘yes’ to Mattarella; all the major parties (with the exception of Meloni's Brothers of Italy) said ‘yes’ to the new government; and all this resulted in a government with a level not seen in decades. And while Draghi took charge of the Council of Ministers, the then director general of the Bank of Italy (Daniele Franco) agreed to take the portfolio of Economy and Finance. In fact, all the important portfolios were occupied by Draghi's men, leaving the rest to representatives of Five Stars, the League, Forza Italia, PD and even Free and Equal.

Time showed that Mattarella had been right to back a government of independents. Five Star and the League liquidated him when the legislature still had half a year to go, but the Draghi Government managed to ensure that in the years 2021-22 the Gross Domestic Product grew by more than 12 points; that a complete vaccination programme was carried out; and that a unique ‘national emergency’ could be faced with the greatest of guarantees.

Mattarella's second term

By that time, Mattarella had been forced to accept a second term, as the political class was unable to agree on a successor. Salvini, who decided to assume the role of ‘king-maker’, did not want to see that his coalition partner Meloni was already on the rise and that the only real candidate was the one who could not be, Mario Draghi, because it was robbing Peter to pay Paul.

After six days of deliberations, eight votes and one failed candidate (Maria Elisabetta Casselatti, president of the Senate), all the political forces except Meloni's party went to ask Mattarella, who had already arranged everything so that he could retire peacefully in his native Sicily (in July 2021 he would have been 80 years old), to repeat as head of state, and Mattarella had no but to accept.

The last ‘masterful’ performance of the re-elected President of the Republic took place after the general elections of September 2022. Meloni, from Rome, clearly won the elections, adding up, together with the other two centre-right parties (Forza Italia and the League), more than 42% of the votes.

In turn, the centre-left presented itself divided into three different factions (PD and allies, Five Star Movement and the ‘Terzo Polo’). The electoral law (Rosatellum bis, approved in October 2017) favoured coalitions over parties running alone, which made the centre-right's victory even more resounding from a parliamentary point of view.

In a Parliament that, following a constitutional ‘referendum’ held in September 2020, had approved a ‘taglio’ or reduction in the number of its components (the lower house went from 630 to 400 members, and the upper house from 315 to 200), the centre-right had a very large majority (in the Senate alone it had 120 of the aforementioned 200 components ) and left the opposition as ‘mere extras’ for a legislature that is unlikely to last until the end, scheduled for September 2027. Although we already know that, in politics, and even more so in Italian politics, anything can happen.

Meloni's rise

The ‘maggioranza’, in this case, was very clear, but not the composition of the Executive. Moreover, the Christian Democrat Mattarella disliked the League as much as the post-fascists of Brothers of Italy, although many did not want to see that Meloni was not Mussolini's ‘political granddaughter’, but the representative of a party that had been in the temperate zone for decades. Matteo Renzi himself, when it came to voting for confidence in the new government, made it very clear: ‘We are facing a right-wing government’. In other words, neither centre-right (because Forza Italia had a third of the votes of Meloni's party), nor post-fascist, nor neo-fascist.

Despite this, more than two years after the Meloni government was formed, part of the press continues to refer to Meloni as an ‘ultra-right leader’: is this possible in a country where there is a Christian Democrat President of the Republic, not one but two chambers with equal legislative capacity, and an independent judiciary, although it could be more so?

That said, Mattarella had to win the trust of Meloni, who, in the presidential elections, had presented his own candidate (the prestigious magistrate Nordio, famous for his work against the Red Brigades terrorists). And here he made it clear that he was the one who had the last word in four key portfolios: Economy and Finance, Defence, Interior and Justice.

In the case of Economy and Finance, Meloni had no candidate: he had ‘bluffed’ that Fabio Panetta, a member of the ECB board, would be his candidate for this portfolio, knowing that Panetta would keep quiet because he was planning to become president of the Bank of Italy, taking into account that the current governor (Ignazio Visco) was about to retire.

With Draghi's intervention, it was decided that the only politician who had been in the economic area during the previous government (Giancarlo Giorgetti, a very important man in the League for many years) because he had been the head of Economic Development, would take over Economy and Finance.

Eventually, Panetta returned to Rome, chosen by President Meloni, but not to be Minister of Economy and Finance, but as the new governor of the Bank of Italy.

Matteo Piantedosi was chosen for the Interior Ministry, a person who had been working in this Ministry since the end of the 1990s: the most important thing for Mattarella was that Salvini could not return to this Ministry, where he had caused him many problems with the European Union between June 2018 and August 2019, and Meloni had no major problem with this, since in the end Salvini was able to return to being Deputy Prime Minister, but now in charge of Infrastructure, a much less glamorous portfolio but not an insignificant one for a politician who had obtained less than half the votes in the 2018 elections.

It was in the Ministry of Justice where the greatest conflict arose: Forza Italia wanted one of their own, Licia Ronzulli, but neither Mattarella nor, even less so, Meloni wanted her, knowing that they could count on Nordio. It was there that Mattarella and Meloni did join forces, despite the conflict this generated within the coalition.

Of course, there was a not inconsiderable compensation for Forza Italia: to grant the other vice-presidency of the government to Antonio Tajani, a prominent pro-European (he had been a member of parliament, commissioner, vice-president of the European Commission and even president of the European Parliament), who would also assume the portfolio of Foreign Affairs. This was very important considering that Meloni was not liked among the community authorities due to her well-known ‘Euroscepticism’.

Given that the Foreign Minister is the person who usually accompanies the head of government to European summits, Tajani was the best possible name for Meloni to become increasingly accepted, as has indeed been the case.

In any case, if there was one appointment with which Mattarella won over Meloni, it was with Defence. Knowing that the Roman politician's political CV was rather scarce and that she needed to be surrounded by her most trusted people, the President of the Republic gave the portfolio to Guido Crosseto, co-founder with Meloni of Brothers of Italy.

Paradoxically, neither Crosseto wanted to be minister, nor should Mattarella have appointed him, as he was none other than the president of the Defence Industry Association, which meant incurring a flagrant conflict of interests. Knowing that it was a very delicate portfolio (even more so with the serious migration problem that the country has been suffering from for decades), Mattarella accepted Meloni's request and Crosseto became the new Minister of Defence.

Two and a half years of peace

Although the country has returned to very low levels of growth (which have a lot to do with the rising cost of raw materials and the increase in the cost of energy), the reality is that transalpine politics has become, since 22 October 2022 (the date of the inauguration of the Meloni Government) a true haven of peace. The peace that Mattarella experienced between February 2015 and April-May 2018 has now been restored in the almost two and a half years that the Meloni government has been in power.

With time it has become known (because Bruno Vespa told it in his book ‘Quirinale’, published at the end of 2021) that Mattarella was already a candidate for the Presidency of the Republic in 2013. Essentially, he met all the requirements: he had been a member of parliament since 1983, a minister on several occasions, on one occasion deputy prime minister and a member of the Superior Council of Magistrates, as well as the son of a minister (Bernardo Mattarella) and the brother of a president of the Region of Sicily assassinated by the Cosa Nostra (Piersanti Mattarella).

an impeccable decade in the exercise of the highest office of state. Now the veteran Mattarella, 83 years old, is heading towards a new full year as head of state, with a mandate until 2029. It had to be a Christian Democrat who became the longest-serving president of the Republic, precisely in a country where this political current was able to govern uninterruptedly for almost five full decades.

Pablo Martín de Santa Olalla Saludes, lecturer at the Camilo José Cela University (UCJC) and author of the book Italia, 2018-2023. De la esperanza a la desafección (Madrid, Liber Factory, 2023).