Guterres calls for African counter-terrorism force in the Sahel

The hasty departure of NATO allied forces from Afghanistan, described as an "American defeat" or "Western capitulation" by much of Islamism, could encourage the most radical forces to create a similar scenario throughout the Sahel strip. It is a fear that both the most affected African leaders and the French president, Emmanuel Macron, who first promoted the so-called Operation Barkhane and now the withdrawal of his military, after seeing the enormous disproportion between the gigantic war and financial effort and the ultimately meagre results, had warned of.

Now it is UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres who is most concerned that the Sahel becomes another kind of Afghanistan, in whose sands lives and resources are buried without end in order to combat a terrorism that threatens to expand at full speed. In a lengthy interview with Agence France Presse, Guterres expressed his fear of "the enthusiasm of the terrorist groups in the Sahel, the result of the strong psychological impact they have experienced in the wake of the Taliban takeover".

Guterres also expressed his concern about the growing power of "fanatical groups, ready to do anything". We have already seen," says the head of the United Nations, "how regular armies disintegrate when confronted with them," and he specifically cites the examples of Mosul in Iraq, Mali, during the first offensive on Bamako, and a few months ago in Mozambique. These examples are sufficiently eloquent to make it essential for the international community to organise itself and prepare to combat the terrorist threat effectively.

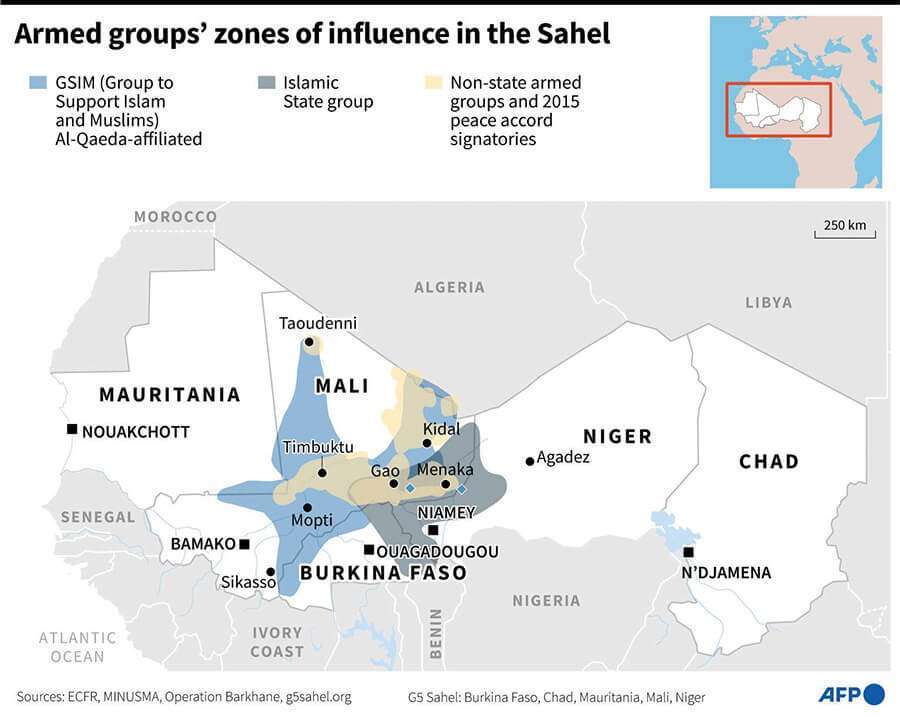

In recent months, in fact, the security mechanisms in the Sahel have been showing more and more cracks, so that, in addition to the terrorist war being waged with greater or lesser intensity in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, it is spreading to other countries, such as Benin, Togo and Côte d'Ivoire. The case of Nigeria, where Boko Haram regularly sows terror through the mass abduction of students and punitive raids and expeditions in many rural areas, is also in danger of spilling over, especially following the assassination of Abubakar Shekau last May. The struggle to succeed him at the head of Boko Haram may give rise to new, even more fanatical and bloodthirsty groups, even as they demonstrate a supposedly greater commitment to "jihad".

Currently, the most active and powerful terrorist groups in the Sahel are JNIM (Jama `atNasr Al Islam WalMuslimin, Support Front for Islam and Muslims) and EIGS (Islamic State in the Greater Sahara). Both are respective branches of AQIM (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the result of the 2007 merger of Al Qaeda with the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, GSPC) and Daesh (see the extensive report by Margarita Arredondas, published in Atalayar on 21 June).

For the UN leader, it is essential to create "an African anti-terrorist force, with an explicit mandate under chapter seven (the one that provides for the use of force) of the Security Council, with the corresponding funding, a force that is capable of guaranteeing a response at the level of the threat".

The idea of Portugal's Antonio Guterres is as laudable as it is dubious in practice. The bad example of Afghanistan, whose army, well trained and equipped by the Americans, gave up as soon as it came face to face with the Taliban, could also spread to Africa's sensitive Sahel region, where the vastness of the terrain, the scarcity and shortages of military personnel and the undeniable corruption could make them easy prey for fanatical Islamist militants, haters of anything that smells of the West, ready to destroy and slit their throats without the slightest contemplation.

This is not the first time Guterres has put forward his idea. Since the beginning of his leadership of the UN, he has sought to create a force that he calls the G5 Sahel, comprising Chad, Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Supported by France, the idea has not, however, found the decisive backing of the United States, both to provide it with a collective UN mandate and with the huge financial resources that would be required. To put it bluntly, neither Donald Trump nor now Joe Biden have confidence in the neutrality of this army of exclusively African blue helmets, and a repeat of the ill-fated experience with the evaporating armed forces in Afghanistan.