The Venezuelan quarantine, a volatile reality at three speeds

At the door of their house, three neighbors chat like any other day in the popular Caracas neighborhood of Catia. Around them, as if the pandemic were already a bad dream of the past, hundreds of vendors crowd in. This week, Venezuela has completed four months of a total chimerical quarantine.

"No, how am I going to stay at home? I have to go out, otherwise how do I survive," he explains to Efe René Solarte, an informal vendor who, like 60 percent of his compatriots, must go out into the streets every day to make a living. Even those with a job and a derisory salary at the end of the month have to resort to supplementary work to survive.

This quarantine only brings a smile to René's face under a handmade mask that does little more than its name promises, covers half of his face, but does little to filter out.

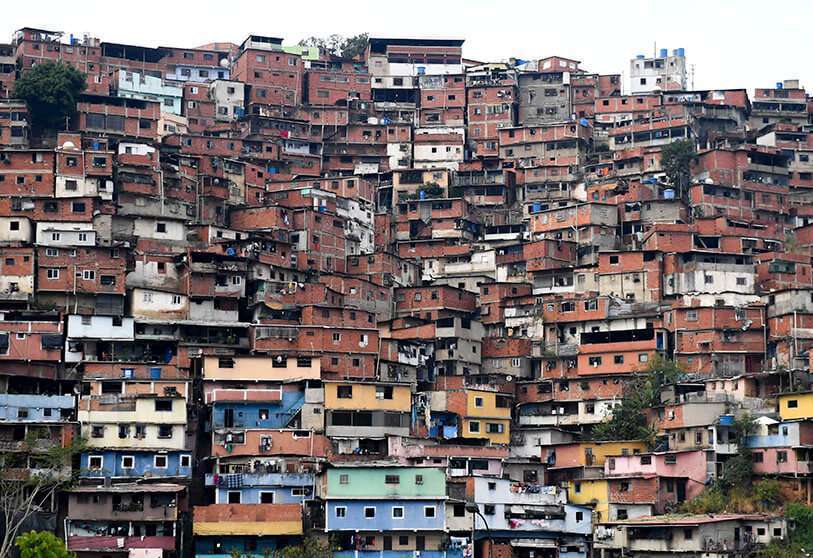

In this immense sector of commercial tradition and popular air at the entrance to Caracas, where the lower areas are more controllable and the rest climb the mountain as if to escape from itself, life has not frozen over.

But the police do patrol and try to bring order and control. That's why Rene stops showing off his merchandise (garlic, ginger and the sweet papelón). The agents of the Special Action Forces (FAES) come and there's a disruption. If they take away the goods they have bought in the morning they will have nothing to put in their mouths.

In Caracas, as in much of Latin America, they earn their bread every day. The difference is that the seven years of economic disaster have turned most people's salaries into a merely decorative figure that must be supplemented in order to make ends meet. Or of the week.

That is why René, an emigrant who returned to his country years ago and who remembers the Canary Islands with special affection, goes out every day at 4 a.m. to the wholesale market, buys what he must sell that day and subsists on the nearly ten dollars he earns on average per day. There is no alternative.

Others find it even more difficult because there are many who sell "fruit and other things which, if they don't get them out immediately, will decompose tomorrow". That explains the races to the nearest door where a neighbor who is not in the conversation allows the workers to hide from the police, who seem to give no respite.

The outlook is not very rosy for those in Catia who struggle daily in formal shops like Alexander Pita, owner of a fruit shop not far from the door that gave shelter to those who were hiding from the agents.

"It has been super difficult because people live from day to day and (the fruit) is a very delicate commodity. They let us work half the day, sometimes until 9 a.m., there have been days when it's 9 a.m. and they send you to close down, here the merchandise is damaged too much and there's no one to replace it," he explains in a room equipped with the basics, without refrigeration and practically empty of produce. For him, as for many others, the four months of quarantine, which has been relaxed for only two weeks for some sectors of the economy, is becoming eternal.

Even more so with the fear generated by a new and unknown virus that seems impossible to control in an area where even used bags are sold, where the lack of hygiene, water shortage and the crowding of people seems the perfect seed for a big outbreak.

One hundred and twenty days of abnormality, effort and struggle, the fruits of which do not arrive. Venezuela continues to add more and more cases of COVID-19 every day in the midst of an intermittent system of flexibilization-restriction that, so far, has not been successful.

Meanwhile, the country already has more than 96 deaths from the virus and about 10,000 infected, including governors, mayors, deputies, constituents, ministers and senior leaders, all infected in the last week.

The situation is analogous to that at the other end of the Venezuelan capital, Petare, where they are proudly considered the largest favela in Venezuela. There, people also live day by day. Between the two, there is an intermediate sector that ranges from the battered middle class to the small bubbles where going to an office is the usual landscape.

This is the case of the centrally located boulevard of Sabana Grande, an old dream for small and medium sized merchants, where those with a steady salary at the end of the month walk among the shops that were once stylish European style cafés.

Today they are ice-cream shops, household appliance shops or clothing stores to stroll through and where you can take a breath of fresh air during a 72-hour government imposed quarantine. The traffic is much less than a day before the pandemic changed everything.

On the boulevard walks Juana Llanes, a nurse who, after four months of hard work, begins to enjoy her vacation. She can wait at home with the strength of a non-floating but steady salary at the end of the month.

"Today we go out and that's because she went to the doctor, (we are) locked up, we don't make visits, we go out to buy nothing else. I'm on holiday at my job and I'm taking advantage of it not to go out because it's difficult," explains Juana, who has taken advantage of the trip to the doctor's with her niece to enjoy some time in the sun. Here, they are beginning to look more appropriate and some latex gloves are sticking out.

And of course, even further away lives that scarce 5% who live the luxury of normality, those with whom the crisis has been more benevolent and who can indulge in whims that in other places would only be everyday life: buying a chocolate, going to the cinema or paying the supermarket bill without paying so much attention to the final cost.

Today, the greatest luxury in areas such as Las Mercedes is being able to make quarantine. Its shopping malls are practically empty, the streets are deserted and just a few vehicles, many of them high-end, drive along the avenues, make a short stop and continue on their way.

There are plenty of masks to prevent infection, gloves and a few plastic shields that cover the face. The fear of COVID-19 is there, but it can be overcome. For the rest, as Rene, the garlic seller, says in universal Spanish: "people are thinking about eating, about surviving, that's the word".