The recognition of black African communities in Spain

The visibility of African communities - for example, those of Equatorial Guinea - in Spain and Europe during the contemporary period is a pending task.

What was known until the present day referred to their anecdotal inclusion in human zoos -events organised to show the world's phenotypic diversity- and forced enlistment in military conflicts (first third of the 20th century), an incipient presence after colonial independence (1950s), a greater prominence with their arrival in small boats through the Strait of Gibraltar (1990s), and migratory flows to Europe through the Mediterranean that would finally make the African presence more visible, albeit at the turn of the century (from 2000 onwards).

Nevertheless, there are extraordinary African traces in Spain between 1870 and the present day: those of the Krio-Fernandina high bourgeoisie, the first documented contemporary African diaspora in Europe.

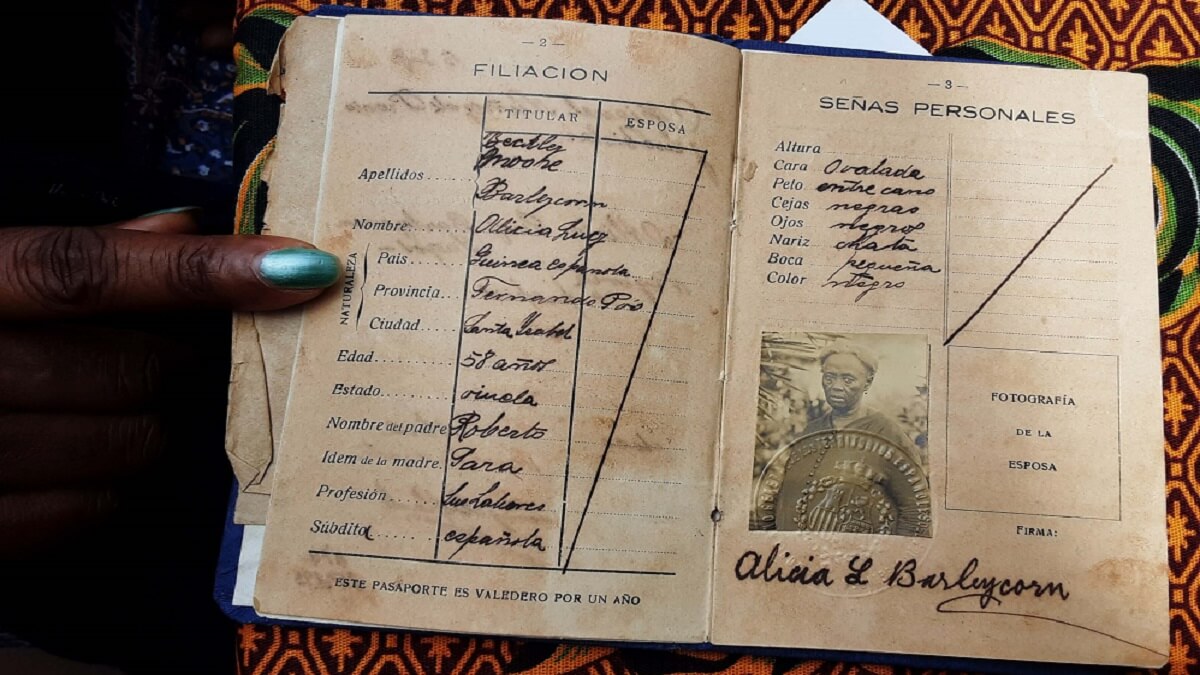

The Fernandine community was a Krio elite, of multi-ethnic origin, educated in the British system, which emerged from 1827 onwards, and lived straddling Africa and Europe. The Fernandine Krians gained great economic power thanks to the support they received from the British and their commercial relationship with the Catalan bourgeoisie. Their power was such that they constituted an Afropolitan, multi-local, transnational, transcontinental and mixed-race African community that broke with the class, race and gender moulds of the time, as there were also completely autonomous Fernandine women moving around the world with complete freedom.

A sketch of the Fernandina community of the late 19th and early 20th centuries would describe them as a group whose appearance was extremely well-groomed, who were elegantly dressed, who were polyglot, with very expensive delicate tastes and very courteous manners.

Among the Fernandina community, one woman stood out, the aristocratic Amelia Barleycorn de Vivour, the richest person in Spanish Guinea in 1890. Years before that date, she was already known for her constant trips back and forth, first to London and then to Barcelona, until her death and burial in the Cementiri de Les Corts in the Catalan capital in 1920. His journeys between Santa Isabel and Barcelona were always in first-class cabins, and gave way to comfortable accommodation in mansions and palaces. And, of course, Amelia Barleycorn travelled in exclusive dresses and jewels, which she kept in noble boots that held her silk and lace clothes, hats and parasols, but also cash in different foreign currencies and, of course, a lot of gold. Their standard of living was not that of the majority of the Guinean-Ecuadorian population, nor was it that of many of the Catalan families in Barcelona at the time.

The reconstruction of the life of the Krio Fernandina in Santa Isabel and Barcelona through documentary archives, oral history, press reports and photographs has made it possible to reconstruct their many encounters, posing to immortalise the day with diners, or sitting in halls or at banquets, with Africans and Catalans alternating among the always elegantly dressed guests.

But Catalonia and Spain, like Europe, have continued to put colonial forgetfulness into practice. Rizo described the Spanish case as one of state promoted amnesia [1]. As Gilroy had denounced, the modern histories of European countries such as Spain should be used to construct arguments amidst the rubble of their colonial extensions that provide consistent responses to immigration [2].

Certainly, the history of the Fernandinos in Barcelona is a clear example of colonial dememory: after having been the city in which they decided to settle down to live between two worlds and two continents, a city in which they celebrated marriages in the Cathedral and in the best hotels, encounters that were covered in the press, the city turned its back on them when the decline of their fortunes and the consequent loss of power came. Proof of this was the brief news item published in 1994 in La Vanguardia, one of the newspapers that had devoted most space to the Fernandinos in the ‘echoes of society’: a descendant of renowned lineages, in this case a Balboa-Dougan, had suffered a racist attack in Barcelona. The news referred to him as ‘negro’ and did not even mention his name, a clear sign that nobody remembered that the Krio-Fernandinos had been a highly respected community in Catalonia since the beginning of the 20th century. This black-African past in Barcelona had been lost until it was fortunately recovered [3].

The krió fernandino in Catalonia is an example of the need to recover these African legacies that urgently require historicisation, because through it we can build solid foundations on which to promote an emotional geography that allows all citizens to move through diversity in less conflict, because it clearly identifies and exemplifies what Black Spain and Black Europe are and what they were, while at the same time revising the debts contracted by Europe in Africa.

The restitution of these traces, like others as yet unidentified, is urgent because the consequence of ignoring blackness in the European past is the breeding ground for racist and exclusionary discourses that deny a historical relationship which, although unforgivably marked by European inequality and abuse, also favoured the creation of transcontinental routes along which not only Spaniards and Europeans transited towards Africa, but also Africans towards Spain and Europe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Yolanda Aixelà-Cabré is a Researcher at IMF-CSIC where she co-directs the Shared Societies Programme and leads the DIVERSE Group.

[1] E. Rizo, ‘Equatorial Guinean Literature in a Context of State-Promoted Amnesia’, World Literature Today, 86(5), 2012.

[2] P. Gilroy, After empire: Melancholia or convivial culture? Routledge, 2004.

[3] In this regard, we recommend Y. Aixelà-Cabré, African women in Africa and Europe (1850-1996), Bellaterra, 2022; Y. Aixelà-Cabré, ‘African Women in Iberia’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 47(7), 2024; or the novel by the African JT. Ávila Laurel, Dientes blancos, piel negra, Bellaterra, 2022.